One in five people who catch the viral disease will end up in hospital.

And for one in 15, it can lead to some incurable and deadly complications.

Outbreaks are being reported in the UK, US and elsewhere due to declining rates of vaccination with the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

In England, the problem has been declared a ‘national incident’, to help health officials take steps to limit further spread across the UK.

There is no specific treatment for measles, so experts are calling on parents to get their children jabbed to give them the best protection from serious illness and death.

Dr David Elliman, of Great Ormond Street Hospital, previously warned the UK could see “dozens of deaths” as cases continue to rise.

“On top of this would be many more hospital admissions, as we have sadly seen in the Midlands, and people left with long-term problems.”

Dr Ronny Cheung of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health said the virus will “at best cause children great discomfort and at worst deaths”.

Here, we look at exactly what to expect if you or your child catches measles, from infection day to rare complications that can emerge seven years later.

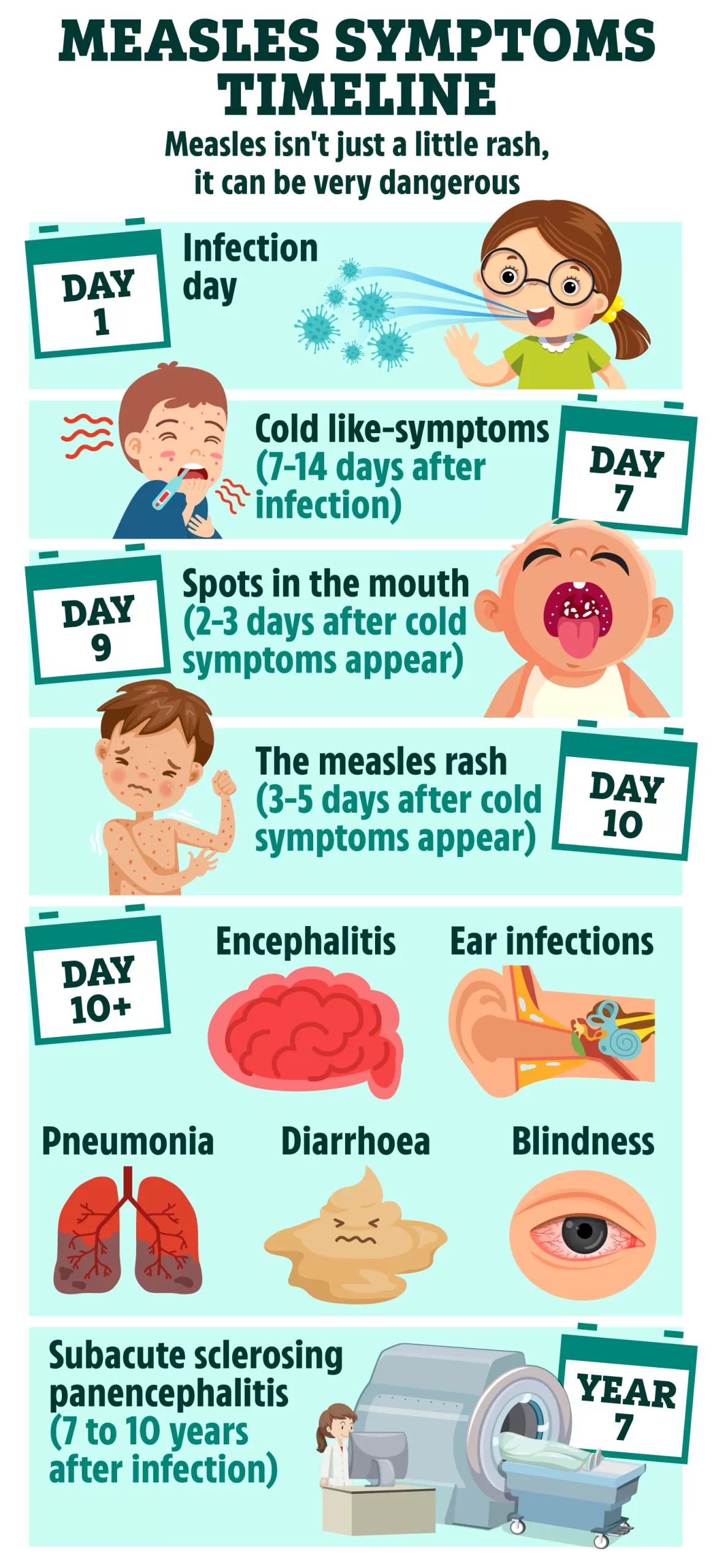

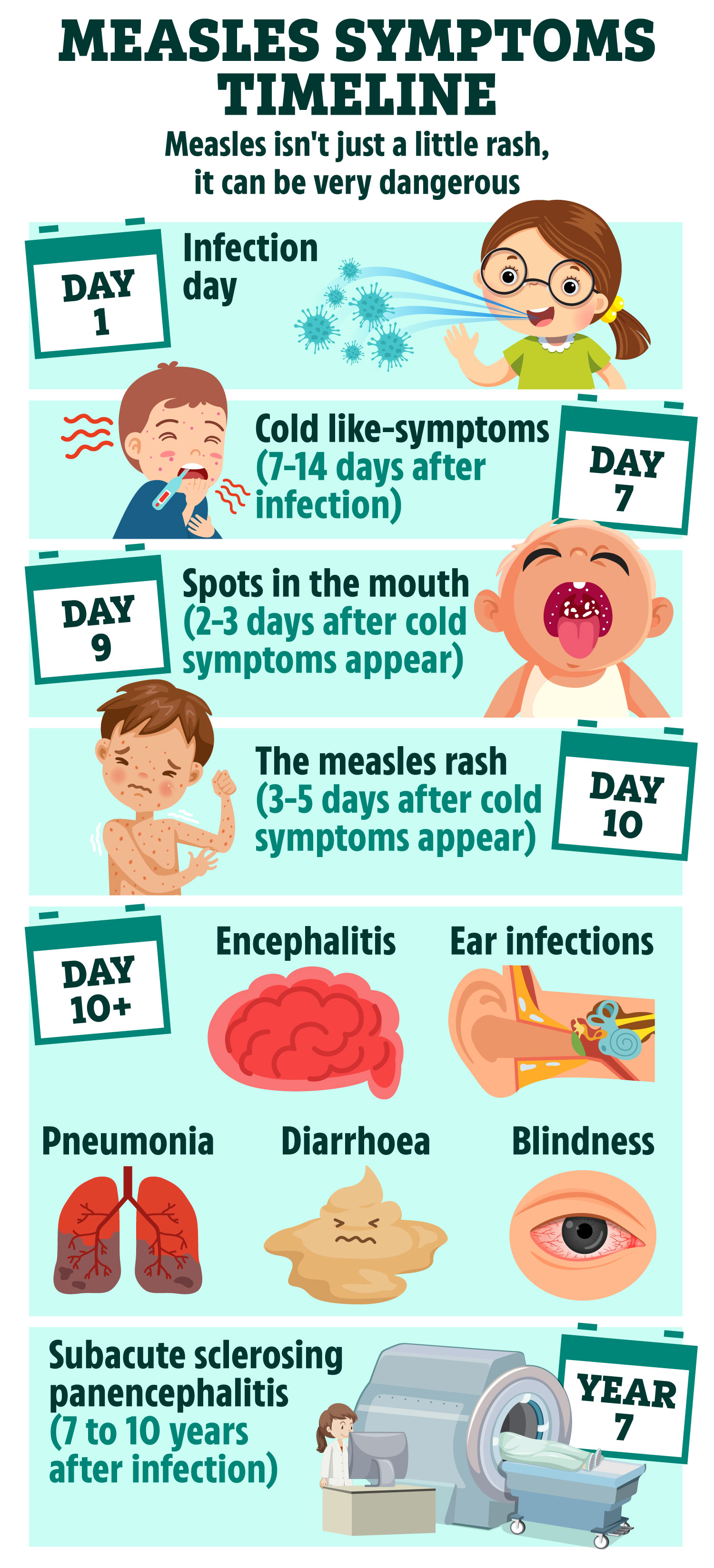

Day 1: Infection

Measles is a highly infectious disease that can spread very easily.

It usually moves from one person to another in water droplets from coughs and sneezes.

It can also be picked up from touching a surface where droplets carrying the virus have landed and then taking the hands to the mouth.

Day 7: Cold-like symptoms

A week to two weeks after infection, a child with measles will feel generally unwell, as if he or she has a bad cold.

Common symptoms include:

- High fever (may spike to more than 40C)

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Red, watery eyes

Days 9-10: White spots

Tiny greyish-white spots may appear inside the cheeks and lips two to three days after cold-like symptoms begin.

These usually disappear quite quickly.

Days 10-12: Measles rash

Three to five days after symptoms emerge, the familiar measles rash starts to break out.

It usually begins on the back of the ears, spreading to the neck, the face and eventually down the body and legs.

The NHS explains what the rash might look like:

- The spots are sometimes raised

- Spots may become joined together as they spread from the head to the rest of the body

- The rash is not usually itchy

- The rash looks brown or red on white skin

- It may be harder to see on brown and black skin

- A person’s fever may spike to more than 40C

Day 10 onwards: Complications

Even for a healthy child, measles is not pleasant and often comes with some complications, which include: diarrhoea, vomiting, eye infection, ear infection and laryngitis.

The high fever can sometimes trigger fits.

Less common complications of measles are meningitis and pneumonia, which affects one in 20 children.

Other nasty side effects include hepatitis and, rarely, encephalitis – inflammation of the brain, which can cause convulsions, blindness, deafness and other long-term damage.

Adults who haven’t been vaccinated or had measles as a child are more likely to suffer from complications.

Year 7+ onwards: Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Measles can, in some rare cases, trigger a brain disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE).

Generally, according to the National Institute of Health, just four to 11 per 100,000 measles cases result in SSPE.

This number jumps up to 18 per 100,000 if the child was less than five years old when infected with the virus.

SSPE lies dormant in the brain for years – and sometimes even decades.

Initial symptoms of the illness are subtle, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders, and may include:

- Mild mental deterioration, such as memory loss

- Changes in behaviour, such as irritability

- Disturbances in motor function, including uncontrollable involuntary jerking movements of the head, torso and limbs

- Seizures

- Blindness

Eventually, patients may fall into a coma or enter a persistent vegetative state.

Death is inevitable as a result of fever, heart failure, or the brain’s inability to control vital organs.

Having an MMR jab is the only way of preventing this deadly complication.

MMR vaccinations and when to have them

IT’S important that jabs are given on time for the best protection, but if you or your child missed a vaccine, contact your GP to catch up.

MMR is part of the NHS Routine Childhood Immunisation Programme.

The first dose is offered at one year, and the second dose at three years and four months.

Parents whose infants missed out, or anyone of any age who has not yet had a vaccine, are urged to come forward.

If you don’t know if you or your child isn’t up to date with their jabs, call your GP for an appointment.

You can catch up on missed vaccines at any age.

Source: NHS