Guatemala City, Guatemala – There were cheers and tears in the upscale hotel in southeast Guatemala City where the Movimiento Semilla, or Seed Movement, held their election viewing party on Sunday, as the reality set in.

The Seed Movement’s presidential candidate Bernardo Arevalo had advanced to the second round of the election, nabbing one of two spots in the August 20 run-off.

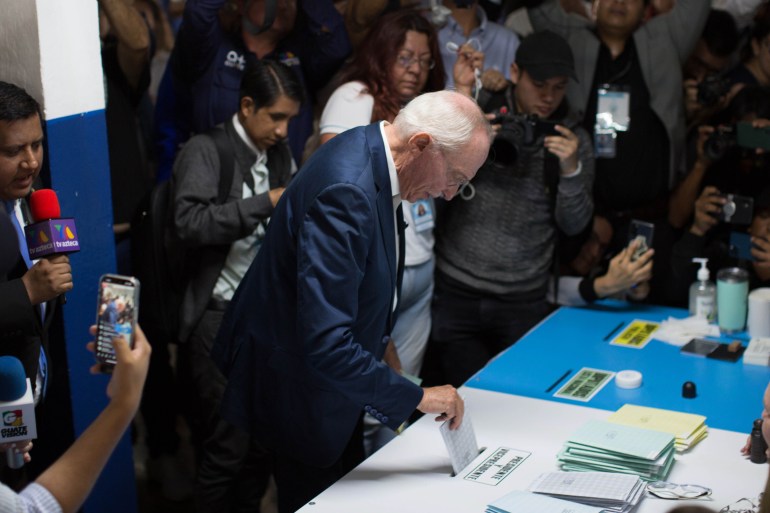

It was a surprisingly strong finish for Arevalo, 64, a congressman and son of Guatemala’s first democratically elected president. He earned 12 percent of the vote, putting him just behind frontrunner Sandra Torres at 15 percent.

His dark-horse success has some experts speculating the results were a rebuke to Guatemala’s political establishment — and the rollback of democratic norms that some critics observe in the country.

“The vote for the Seed Movement means a rejection of corruption, a rejection of traditional parties,” Gabriela Carrera, a political science professor at Rafael Landivar University in Guatemala City, told Al Jazeera.

In recent years, Guatemala has come under scrutiny for alleged attacks on its free press and anti-corruption advocates, leading experts to question its democratic stability.

But political observers like Carrera see the Seed Movement’s success in Sunday’s election as a sign of shifting political tides. Not only did Arevalo advance to the final round of the presidential race, but his party also picked up 24 seats in Congress, an increase from the six they won in the 2019 elections.

Arevalo had campaigned on anti-corruption and improving healthcare and education. In the wake of Sunday’s election results, he also announced that he would work for the return of the nearly three dozen judges, prosecutors, investigators, journalists and activists who have been forced into exile since 2020.

“The message that we presented and the necessity for change are arriving to the population,” Mario Jacobs Lima, an adviser with the Seed Movement, told Al Jazeera at Sunday’s results party.

Torres an early frontrunner

While Arevalo’s second-place finish was unexpected, the success of his rival Torres, a conservative with the National Unity of Hope (UNE) Party, was widely anticipated.

She had consistently topped polls, leading establishment candidates like centrist career diplomat Edmond Mulet and the far-right Zury Rios, the daughter of former Guatemalan dictator Efrain Rios Montt.

Arevalo, meanwhile, polled a distant eighth, with only 2.9 percent of voter support in a June survey.

According to Carrera, the discrepancy between the pre-election polls and Sunday’s results stemmed from having a crowded field of candidates — and the ambivalence of voters. “The polls were wildly variable,” she said.

Torres, however, is a well-known political figure in Guatemala. A former first lady, the 67-year-old businesswoman had sought the presidency in the past two electoral cycles, finishing second in both.

In 2015, she placed behind eventual winner Jimmy Morales and in 2019, she lost to current President Alejandro Giammattei, with whom she later would form an alliance.

Torres campaigned this year on bolstering social programmes to address poverty and implementing a tough-on-crime national security programme, similar to that of President Nayib Bukele in neighbouring El Salvador.

Both she and the UNE party have long been accused of corruption and violating campaign finance laws, allegations they deny.

Widespread ‘protest’ votes

The closely watched race generated greater voter turnout than projected, with 60.47 percent of registered voters casting a ballot. By comparison, in 2019, only 53 percent of eligible voters participated

But Arevalo’s success was not the only surprise of this year’s race. Also notable was the large “protest” vote — with Guatemalans either leaving their ballots empty or invalidating them in other ways.

According to the country’s Supreme Electoral Council, 17.39 percent of the votes were null, while another 7 percent were left blank.

“The Guatemalan citizens shouted with the null vote,” said Ana Maria Mendez, the Central America director for the Washington Office on Latin America, a research and advocacy group.

“It is a rejection of the current electoral political system because it [the system] does not respond to the desires and aspirations of a people tired of corruption.”

Questions of corruption lingered over Sunday’s vote, after Guatemala’s Constitutional Court blocked the candidacy of three major presidential candidates due to alleged irregularities with their paperwork.

They included leftist Indigenous leader Thelma Cabrera, conservative candidate Roberto Arzú and businessman Carlos Pineda, who was leading in the polls in May. Calling the court’s decision “fraud”, Pineda appealed to his supporters to cast null votes to protest his exclusion.

Carrera, the political science professor, called the null votes a “wake-up call” for Guatemalan politics.

“The null vote shows, ‘I still believe that I can have representatives, but they are the ones that do not appear on that ballot,’” Carrera said, explaining the mindset of voters.

She believes the court’s exclusion of the three candidates helped shape Sunday’s results: With fewer competitors, Arevalo stood a better chance of attracting more votes.

The outlook for August

As the August run-off approaches, both Torres and Arevalo will have to “rethink their strategies” to contend with their unexpected face-off, according to Carrera.

“I don’t think even Sandra Torres and UNE were prepared to face the Seed Movement party, nor was the Seed Movement prepared at the time to pass to the second round,” Carrera said.

Both candidates are expected to face an uphill battle. For Arevalo, experts say the challenge is bringing his progressive message to a country where conservatism is deeply embedded.

For her part, Torres must court conservative and far-right political groups that have previously looked upon her with distrust.

According to a survey carried out before the first round of voting by the Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre and the group Pro-Datos, just as many voters said they would cast their ballots against Torres as in support of her.

No matter who wins, the next president of Guatemala faces a country racked with accusations of corruption and the erosion of democratic bulwarks.

Following Sunday’s vote, Arevalo and the Seed Movement rallied in the Constitutional Plaza of Guatemala City to celebrate their electoral victories. But it was a symbolic gathering place: In 2015, thousands of Guatemalans flocked to the plaza to protest official corruption.

“In 2015, it was in the plaza. In 2023, it was in the [ballot boxes],” Mendez said, drawing parallels with the election’s widespread protest votes.

But she added that she senses optimism in the country’s election results: “A window of hope opens with the candidacy of Bernardo Arevalo and the Seed Movement party.”