Armenia’s exploring an associated-state model with India, Russia, and Iran — akin to Andorra’s relationship with Spain and France or Palau’s Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the United States (US)—would be a transformative opportunity.

If executed, such a move would reflect growing concerns over security, economic sustainability, and the shifting dynamics of great-power competition in the South Caucasus. Such an arrangement could formalize Armenia’s partnerships to counterbalance regional pressures from Azerbaijan and Turkey; the divergent interests of India, Russia, and Iran—coupled with the complexities of post-Soviet geopolitics—make this proposition far more challenging than the relatively stable arrangements seen in Andorra or Palau.

Strategic Benefits for Armenia

In the domain of security guarantees, Armenia has increasingly turned to India for arms procurement, with defense deals exceeding USD 800 million since 2022. The defense partnership becoming a formalized alliance could solidify this defense relationship, enabling Armenia to better counter perceived threats from Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Russia, despite its diminished credibility in the region following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, retains significant influence in the South Caucasus even as the region reorients towards Middle Eastern stakeholders.

Russia can still provide residual security support. Meanwhile, due to being perceived by Iran as a buffer state against Russian influence, Iran can serve as a logistical buffer for Armenia to mitigate potential blockades or corridor encroachments by Turkey and Azerbaijan.

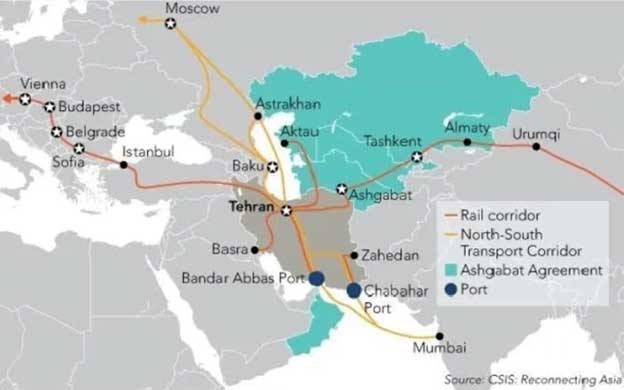

There is also the factor of economic corridor access. Armenia’s strategic location at the crossroads of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) positions it as a critical link between India, Iran, Russia, and Europe. India’s defense backing of Armenia and investments in the Iran–Armenia railway, as well as related infrastructure projects, could help Armenia bypass routes dominated by Azerbaijan.

By leveraging its geographic position, Armenia can generate substantial leverage. Such development also enhances its role as a vital gateway for Eurasian trade, connecting South Asia and the Middle East with European markets through a potential EU membership.

There is also the matter of mitigating the risk of sanctions and diversifying trade. Closer ties with Russia and Iran could provide Armenia access to alternative markets and energy supplies, particularly valuable amid Western sanctions that disrupt global value chains.

Simultaneously, India’s robust ties with the US and the European Union (EU) offer Armenia a counterbalance, helping it avoid over-reliance on any single geopolitical bloc. This will allow it to position itself as an economic connector between various geo-economic blocs.

A lesson to draw from is the case of Singapore. Its strategic position as a conduit for commercial interests among major powers is being challenged by the intensifying US-China rivalry.

As Washington and Beijing transition to prioritizing relative gains over absolute gains, Singapore’s ability to maintain good relations with both powers is becoming increasingly difficult.

The city-state must adapt to these new circumstances, but policy inertia and adjustment costs may hinder its ability to do so. This dilemma may also affect other smaller states that previously benefited from more stable major power relationships.

Potential Advantages for India, Russia, and Iran

There are many advantages to India, Russia, and Iran exploring the tie-up to be sponsors of an Armenian-associated state. It could provide impetus for realizing the currently problematic development of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a proposed 7,200-kilometer transport route connecting Russia to India via Iran, offering a shorter and more economical alternative to the Suez Canal route.

Despite its potential, the project has seen little progress due to a lack of investment from interested parties. However, Russian aggression towards Ukraine has created a new sense of urgency for Russia to secure alternative markets and transport routes, and Iran has committed significant funds, around $13 billion, to develop the necessary infrastructure, including upgrading ports and improving access to the Volga-Don Canal.

For India, it secures trade and transport corridors into Central Asia, Russia, and Europe via Armenia, bolstering the INSTC. It also serves to counter Turkish-Pakistani influence in the region — as well as provide a beachhead to counter Chinese influence — and throughout the Turkic belt that stretches across Central Asia. This is coupled with expanding its lucrative defense exports and strengthening its diplomatic footprint.

For Russia, such an arrangement ties it up with a friendly strategic partner with growing heft (i.e., India) and also permits it to retain a strategic foothold in the South Caucasus, even as Armenia explores closer ties with the West. There are also benefits from Armenia’s role as a conduit for sanctioned trade with Iran, particularly amid tensions with the West.

Finally, Iran can strengthen cross-border trade routes with Armenia, bypassing Azerbaijan and facilitating trade with India and Europe. This reinforces its regional influence following setbacks in Syria and elsewhere and also offers a hedge against Turkish influence — and through them Western and NATO ambitions — in Central Asia.

Infrastructure plays a crucial role in shaping global relationships, fostering interdependence and cooperation among nations. Examples include the Greater Mekong subregion’s power grid, which synchronizes economies, and the Trans-Asian Railway, which connects China, Laos, and Europe.

Water has also become a key aspect of diplomacy, as seen in the Indus Waters Treaty, where technical negotiations and engineering details have helped resolve disputes and promote cooperation between India and Pakistan. Such agreements rely on a combination of political will and technical infrastructure, including dams, grids, and other systems, to facilitate stability and cooperation.

Cooperating together to build a vital segment of the INSTC through Armenia is a means for Iran, Russia, and India to align their strategic and geo-economic interests and build diplomatic capital with each other.

Stability is often achieved through engineered solutions rather than just diplomatic efforts. The success of international agreements relies on a combination of political will and technical infrastructure — dams, grids, servers, and satellites — the technical infrastructure that makes cooperation possible and entrenches economic ties.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) exemplifies this approach, with projects like the Jakarta-Bandung rail and Laos-China railway demonstrating successful partnerships that go beyond construction to establish long-term economic ties. Through the BRI, China is transforming trade routes into economic strongholds, showcasing how infrastructure can anchor both strategic presence and partnership.

In Armenia, financing and developing INSTC infrastructure forges long-term economic ties through maintenance agreements, operational protocols, and financial dependencies. This infrastructure is anchoring both strategic presence and partnership for all countries involved, solidifying relationships and fostering cooperation in the region.

Core Challenges and Risks

But this theory comes with significant challenges. Firstly, Russia and Iran often adopt an anti-Western stance, while India maintains strong partnerships with the US and Europe despite being a strategic partner of Russia.

Reconciling these divergent diplomatic positions within a formal arrangement would be a significant challenge. Additionally, Armenia’s aspiration for a “multi-vector” foreign policy—balancing ties with the EU and the US—could be jeopardized by a deal perceived as overly aligned with Moscow and Tehran.

Escalating tensions between the US, Russia, the EU, and other European nations have created an uncertain environment where countries can no longer rely on each other. Amidst this complexity, dynamic economies in Asia are driving growth and helping to pull the global economy out of recession. China and India are at the forefront, emerging as epicenters for policymakers and world leaders.

According to Nicolas Aguzin, CEO of HKEX, “The shift in economic and geopolitical power is moving East.” An IMF report supports this trend, predicting that Asia’s economy will grow by 50% in the next five years and surpass the G-7’s GDP by 2030.”

Similarly, Armenia’s desire for EU membership is complicated by substantial economic dependencies on Russia, as well as its own de facto alliance with Armenia, India, France, and Greece following the Karabakh war. Additionally, the economic center of gravity is moving towards Asia, and Asian powers are now shaping Europe in a historical reversal.

These countries played a significant role in supporting Armenia after the war. Notably, France supplied Armenia with armored vehicles, which were transported through Georgia, despite the latter’s reluctance to be involved in arms shipments. Iran allegedly facilitated the transfer of weapons from India to Armenia, and Iranian military experts were reportedly present in the country, providing further assistance.

Iran perceives Armenia as a crucial proxy and buffer zone in the region and has consistently opposed efforts to normalize relations between Armenia and its neighbors, Azerbaijan and Turkey. From Tehran’s perspective, normalization undermines its influence and limits its ability to exploit regional contradictions to achieve its strategic objectives.

For instance, by voicing opposition to the Zangezur corridor project, which aims to connect Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave and Turkey, Iran effectively pushes Armenia towards regional isolation. Conversely, if Armenia were to facilitate communication links through its territory, it would gain significant geo-economic and geopolitical leverage, enhancing its own position in the region.”

There is also the risk of creating over-dependence on sanctioned partners. With a GDP of approximately USD 20–25 billion, Armenia risks collateral economic damage by developing a dependency on states under Western sanctions, such as Russia and Iran.

India’s complex relationship with China — the 2024 border deal a momentary rapprochement and a case for military build-up rather than a strategic shift — and China’s further complicate Armenia’s foreign policy calculus, at least when it comes to its involvement with China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) and its geographic distance from Armenia.

This is coupled with how this may shape geopolitical frictions. Azerbaijan — backed by Turkey and Pakistan — may respond with increased aggression if Armenia’s alliances threaten vital trade corridors like the Zangezur corridor. Ongoing territorial disputes and unresolved border issues heighten the risk of escalation.

And when comparing smaller states like Andorra and Palau — which maintain stable associated-state relationships in relatively stable environments— Armenia’s geopolitical environment is far less conducive. Territorial disputes, Russia’s declining reliability, and Iran’s sanctions challenges make a straightforward “associated state” framework highly complex.

Governance in Armenia

Any discussion of reshaping Armenia’s status must consider its internal power dynamics. In Armenia, the prime minister holds the most authority, serving as head of government and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The prime minister sets policies, oversees the cabinet, and is typically appointed by the parliamentary majority.

In contrast, the president is largely a ceremonial figure, responsible for appointing ministers on the prime minister’s recommendation and ensuring constitutional protocols are followed. Consequently, any negotiation regarding a potential associated-state arrangement would be led by the prime minister’s office.

Creating a structure in Armenia akin to Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Office of the High Representative (OHR), which enforces the Dayton Accords and wields broad powers to override local decisions threatening stability. However, key differences and hurdles make this proposal challenging:

· Legal Mandate: The OHR’s authority stems from a UN-endorsed peace agreement (the Dayton Accords). Armenia lacks a comparable international framework, necessitating a new multilateral pact acceptable to all stakeholders.

· Funding and Sanctions Exposure: OHR activities are funded by multiple donors, including the EU and the U.S. In Armenia’s case, sanctions on Russia and Iran complicate funding for a shared governance body, while India would be wary of entanglements that strain its Western partnerships.

· Sovereignty Concerns: The OHR can override Bosnian laws and remove officials. Armenia’s government and public, particularly since the 2018 Velvet Revolution, are unlikely to accept such external interference.

· Competing Interests: Russia, Iran, and India have divergent regional objectives. Establishing a powerful external office could exacerbate rivalries rather than resolve them.

Theoretically, an Armenian OHR could follow the model of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The group consists of three members, each representing a different country: India, Iran, and Russia. Together, they serve a six-year term, with the option to serve up to two consecutive terms. Notably, there is no overall limit to the number of terms they can serve.

As a collective body representing the interests of Armenia’s sponsors, the group shares leadership. However, one member is chosen as chairperson, a role that rotates every eight months among the three members or, alternatively, every two years. The member with the most overall votes becomes the first chairperson, setting the rotation in motion for the six-year term.

This OHR can then advise and coordinate with Armenia’s president and prime minister to share their views and provide a central forum for discussing and advising on infrastructure projects and foreign policy.

Another approach is to form and lead an INTSC Forum, a collaborative platform for public sector organizations, private enterprise players, banks, and other stakeholders from India, Russia, and Iran to establish protocols and technical standards, as well as coordinate on the development of INTSC projects in Armenia.

The forum will comprise plenary sessions, technical committees, and working groups to develop and implement specific projects, with key activities including protocol development, technical standardization, project coordination, capacity building, and investment promotion.

By harmonizing standards, increasing efficiency, and enhancing cooperation, the forum aims to contribute to economic growth and development in Armenia and the region, with participating organizations including public sector entities, private companies, banks, and international organizations.

Other alternative approaches that Armenia can take are

· Focused Bilateral Agreements: Armenia could deepen separate defense, trade, or infrastructure deals with each partner, mitigating risks. For instance, it could strengthen defense ties with India, maintain practical relations with Russia through the Eurasian Economic Union, and pursue energy or transport projects with Iran without creating a joint oversight body.

· Informal Coordination Platforms: Instead of a supranational entity, Armenia could form issue-specific working groups for security, transit, or sanctions mitigation, retaining policy flexibility.

Conclusion

Pursuing an associated-state model with India, Russia, and Iran offers Armenia the potential for enhanced security, expanded trade corridors, and a diplomatic hedge against regional rivals. Or even an arrangement that positions them as sponsors of Armenia due to a convergence of strategic interests. However, the disparities among these nations’ geopolitical interests, coupled with concerns about sanctions and sovereignty, pose significant challenges.

A key lesson from smaller associated states like Andorra and Palau is that enduring partnerships require relatively stable environments with fewer major-power rivalries. Armenia’s context—marked by territorial disputes, shifting alliances, and broader East-West tensions—is far more complex.

In the near term, Armenia may benefit more from a strategy of selective engagement:

1. Maintain Strategic Autonomy: Continue engaging with Western entities to balance Russian and Iranian pressures.

2. Focus on Bilateral Projects: Prioritize distinct, carefully structured deals with India, Russia, and Iran rather than an overarching tripartite treaty.

3. Avoid Overreach: While a Bosnia-style OHR might offer coordination, it is unlikely to gain traction without international mandates and broad domestic acceptance.

Armenia must balance its options while avoiding entanglement in Great Power rivalries, prioritizing its sovereignty and economic stability in a geopolitically complex region. To do so, it needs to develop the capacity to shape its own rules and destiny, rather than simply following the rules set by larger powers.