On the Shelf

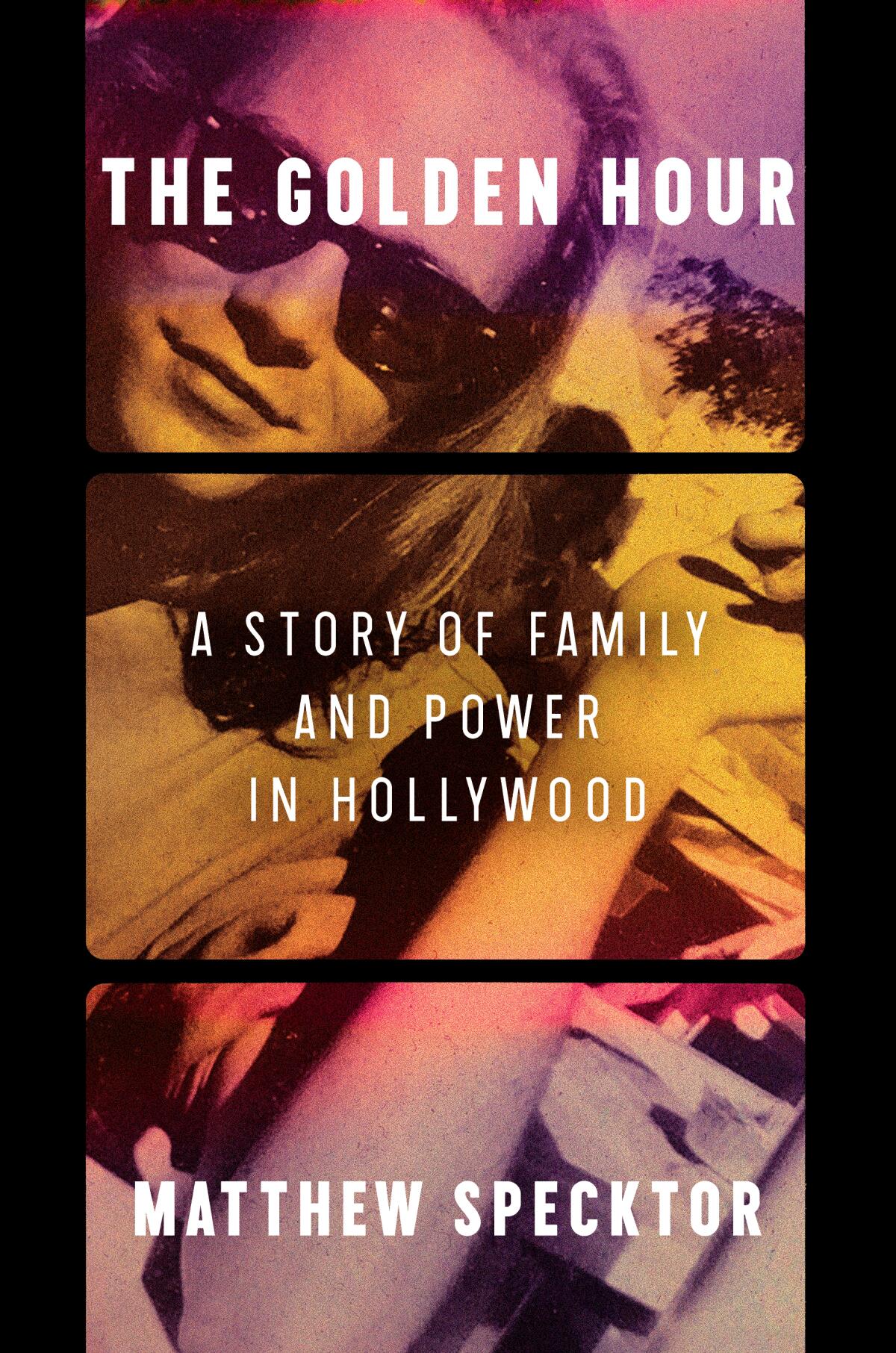

The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood

By Matthew Specktor

Ecco: 384 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Matthew Specktor is aware that his third book about Los Angeles is landing during a fraught time. “The pleasure of making beautiful things and reveling in beautiful things and making art is a bizarre thing in America,” Specktor said during a video call in late March. “There’s a Calvinist streak in the American spirit and nature that is so deeply mistrustful of pleasure. And right now, it’s coterminous with fascism, where there shouldn’t be any pleasure for its own sake.”

The new book, “The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood,” is a history of the film industry beginning in the 1950s. It’s the completion of a book trilogy — what Specktor refers to as a “triptych” — two memoirs and a novel about L.A. and the people who have journeyed there in search of the American dream.

The touchstone for Specktor in his second book, “Always Crashing in the Same Car,” was F. Scott Fitzgerald. In his latest, it’s his parents: dad Fred Specktor, a legendary talent agent who recently celebrated his 90th birthday and is still working, and mom Katherine McGaffey Howe, a screenwriter who died in 2009.

His parents were elusive figures when Specktor was growing up. His dad worked long hours and didn’t talk much at home; his “beautiful and funny” mother never found her creative niche. Some of the most painful scenes in the book are Specktor’s memories of his mom: “a wonderful parent and a terrible, Medean nightmare.” She frequently took Specktor to the movies or watched films with him at home, but her alcoholism led to many nights in which Specktor assumed the role of caretaker. Specktor was forced to get his mom, inebriated and sometimes unconscious, to her room safely.

The narrative of his father begins with an anecdote about a disastrous outing to see a film. When he invited his date out for dinner afterward, she turned him down because he couldn’t afford an expensive restaurant, and in her parting words, told him that he’d make a lot more money as an agent. Within a few weeks, he began working for Music Corporation of America. Parts of Specktor’s narrative were gleaned in formal interviews with his dad. His dad’s customary reticence meant Specktor had work to do.

While Fred Specktor provided an entry point, Specktor says he continues to be fascinated by agents in general. He finds the stereotypical depictions of agents as hard-driving, hard-drinking men and women who exploit their clients as cartoonish. “Agents exist at the precise point where art and commerce allied.”

Part of the misconception about agents comes from the belief that everyone who works in the film industry is wealthy. Far from it. In the post-COVID film industry, the middle-class salaries of Hollywood workers are disappearing, while most actors are broke.

“[The agents I knew] had real consciences about what they were and what they were advocating for. It’s my stubborn belief that art wants to be free. The agent is not only there to make it possible for the artist to succeed financially, and while not being a cheerleader, but the person who is encouraging the artists to continue to express themselves,” Specktor said.

In a second interview, conducted earlier this month, Specktor discussed the decline of the middle-class film, his dad’s legacy and making sense of his troubled relationship with his mom.

You describe the three books as a triptych rather than a trilogy. Can you talk about which you would make the centerpiece and how you see the other two relating? As an artist, what do you want readers to take away from this project?

“Triptych” would definitely be the word. They’re not sequential and each book is complete in itself, but they do shed light on one another and on certain mythologies: questions of success and failure, image and reality, and of America’s influence both internally (i.e. upon the psyche of its citizens) and abroad. I’d hope readers would come away from them with a sense of having touched something much larger than “Hollywood” as it is commonly understood. This is an American literary project, not just a Los Angeles one. As for a centerpiece, that’s impossible for me to say, only because the books are quite different. I will say “The Golden Hour” feels like a … culmination in some sense. It’s the one that articulates the project most fully.

As a longtime resident of L.A., do you consider Hollywood to be the city’s beating heart? If Hollywood continues to suffer the effects of the decline in cinema attendance, what happens to the larger city?

Metaphorically, perhaps, but in reality, no. Most people who live here have nothing to do with the film industry — it’s a huge city, and I think it’s less than 5% of the workforce here that’s employed in entertainment. But the loss of that metaphorical heart — and I do think the movie business as we’ve long understood it is never coming back; it’s a subsidiary of the tech industry now, no longer an industry unto itself — is meaningful. I think Hollywood used to propose itself as a place where artists and creative people could sustain themselves, perhaps even strike it rich, and that’s gone. The loss of that idea is … incalculable. It erodes the soul of the city in ways that are painful to consider. This used to be a city to dream of and I don’t think it really is that anymore.

You and your family were affected by the firestorms in January. Can you talk about the neighborhood and its history? What do people not know about it?

My sister lost her house. My parents had to evacuate, although their house thankfully survived. This city will never be the same, insofar as our sense of safety, our illusions of permanence and so on, are gone. But I think there was some sense, particularly with the Palisades fire, where many people may have thought, “Oh, it’s just a bunch of rich people losing their homes.” Not so. Both Malibu and the Palisades had many middle-class residents — when I was growing up, the Palisades in particular was a firmly middle-class community, not a wealthy one, and not one where people in showbiz were concentrated — and those are the people who’ve been displaced. Rick Caruso may have been able to protect his property with private firefighters, but middle-class and working people received no benefit from this at all. Those are the people who suffered.

You have spoken about the decline of the “middle-class” film. Can you talk about what that means and what it means for the movie industry?

I think the turn towards the blockbuster, which we’ve seen over the last 50 years, is a kind of fascist turn. When you stop making middle-class movies — movies with a moderate budget, as opposed to ones made on a shoestring or ones that cost $200 million — you’re hollowing out a middle class of people who make them. Those budgetary extremes are essentially saying, “We’re going to pay a few people a ton of money and most people a lot less.” That’s a recipe for disaster. That’s how you arrive at people like David Zaslav, whose only legible passion appears to be cost-cutting — taking other people’s money and reallocating it to himself and to his shareholders — in a position of power in what’s nominally still a creative industry. As for the fact that so many of those blockbusters, particularly in the last 20 years, seem to revolve around superheroes and vigilantes — people who alone can fix things, strongman types — well, I’ll let that speak for itself.

What do you think, based on your long interviews with your dad, is the legacy he hopes he’s remembered for?

I think he’d like to be remembered as an ethical person, rather than as a merely successful one. It’s always been important to him to be decent, in a business that isn’t particularly. I don’t delude myself that my dad is a saint, but I think if you ask anyone in Hollywood, they’ll say he’s a good guy, in ways that are rare for a talent agent (or for anyone these days). And he is! He said to me recently he wants to be remembered as the father of a great writer and [laughs] I hope he is, but I’m going to remember him as a genuinely good person.

You speak about some very painful instances where you were forced to care for your mother when she was drunk. Can you talk about how that affected you as a kid, but also your relationship with her? Did you feel that you had resolved things with her by the time she died? Or do you think that by writing this book and “Always Crashing,” that you’ve come to a new understanding or resolution about her?

I definitely had not resolved things at the time she passed in 2009. The scars, the emotional scars, are still there. But I loved her and I admire her more as I get older. She was trapped in a world that wasn’t going to give her much opportunity to become the best iteration of herself — the misogyny of Hollywood in the ‘60s and ‘70s (and later) can’t really be understated — and she fought valiantly. And even at her worst, her cruelty was offset by a love of film and literature. We saw so many films together and read so many novels. Given that those things are such a huge part of my life … it was an enormous gift she gave me, truly.

Specktor and Griffin Dunne will be interviewed by David Ulin at 12 p.m. on April 26 at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books.