SACRAMENTO — When the state of California paid prison supervising dentist George Soohoo $1.2 million last year, it wasn’t for a job well done. It was for vacation never taken.

Soohoo joined the rare club of state employee millionaires by cashing out thousands of hours of unused time off when he retired, setting a new record for the payouts. He topped a list of nearly 1,000 workers who left state service last year with $100,0000 or more in banked leave benefits, a Los Angeles Times analysis of state payroll records found. In all, California paid departing workers $413 million last year for unused time off.

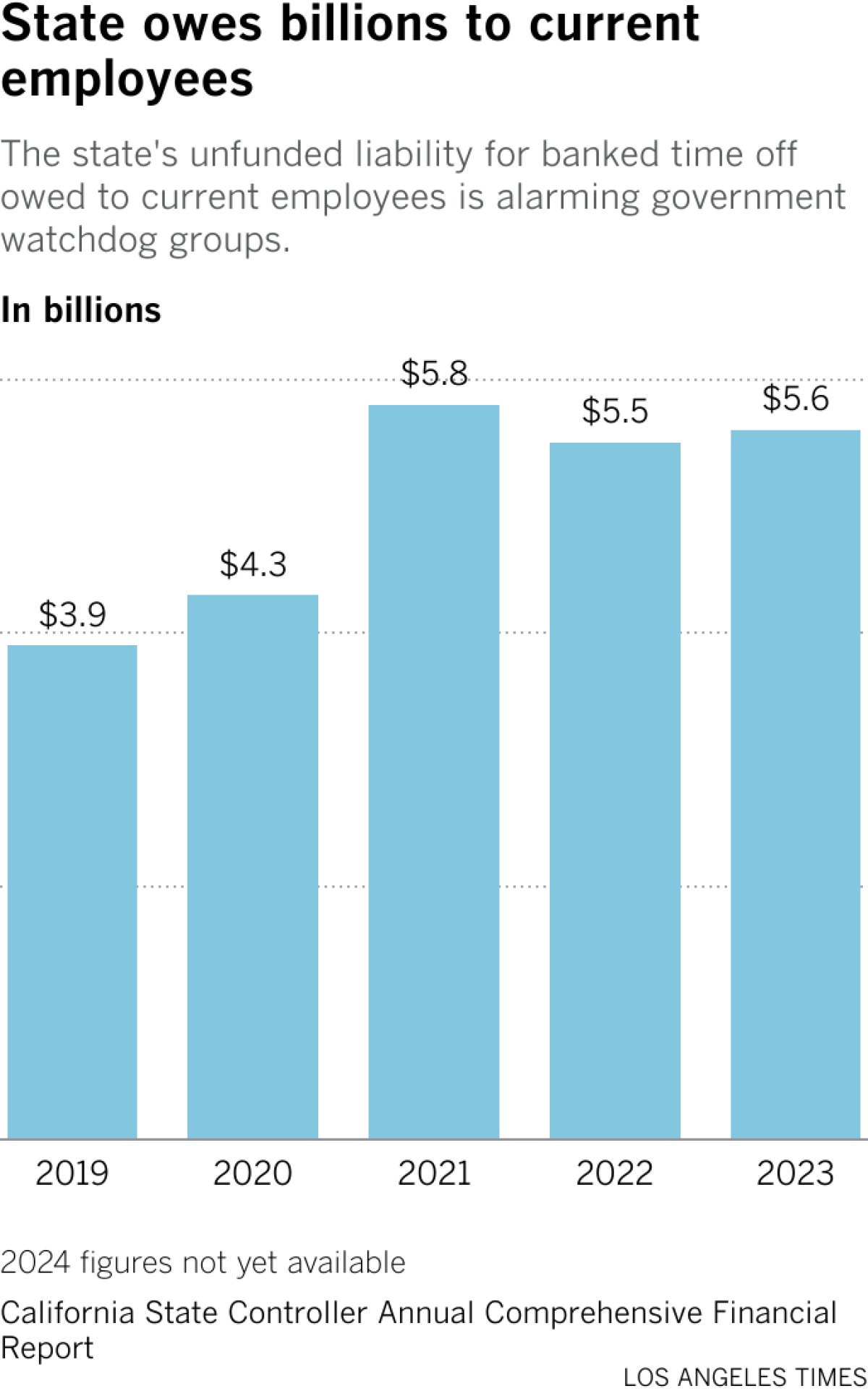

That’s nothing compared with the massive financial liability the state faces for the banked time off still on the books, alarming government watchdog groups.

“I’m more disturbed than I am surprised,” said John Moorlach, a former Republican state senator from Orange County and current director at the Center for Public Accountability at the California Policy Center, a conservative think tank. “This is going to be a serious problem down the road.”

The state’s unfunded liability for vacation and other leave benefits owed to current employees ballooned to $5.6 billion in 2023, according to the most recent financial accounting report issued by the state controller’s office. That’s up nearly 45% since 2019, the year before COVID-19 curtailed travel and temporary work-from-home policies left fewer workers taking time off. Over the past six years, the number of retirees paid at least $250,000 in banked vacation time increased nearly fivefold to 73 employees last year.

The rising liability stems from generous time-off provisions for state employees — including vacation accrual of up to six weeks a year, 11 state holidays, a personal holiday and professional development days — and a failure to enforce policies that cap vacation balances for most employees at 640 hours.

While the amount of unused leave becomes public when an employee is paid out after leaving state service, the controller’s office would not provide the number of vacation days on the books for current employees, saying the information was confidential. However, the controller’s office did provide totals for unused time off by department for those using the state’s leave accounting system. That includes the vast majority of state agencies. It does not include legislative employees or local governments.

The data showed state employees had 110 million hours of leave on the books as of December, although 40 million of those were sick leave and educational leave time that can’t be cashed out when workers retire or otherwise leave state employment. Those unused hours can, however, be converted to service credit to increase their government pensions.

Among state agencies, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has the most leave time on the books with 22 million hours, according to records from the controller’s office.

“There’s no parallel to this in the private sector,” said Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Assn. “Obviously this is a problem.”

Theresa Adams, an advisor for the trade organization the Society for Human Resource Management, said many employees in the private sector don’t use all of their vacation time, perhaps not wanting to burden their co-workers or believing it increases job security. But there typically isn’t a financial incentive to do so because many employers have caps on how much vacation time can be accrued, she said.

Last year, the 10 employees with the largest vacation payouts in California took home a combined $5.3 million. For those retirees, the time paid out was the equivalent of taking a year or more of vacation. In the case of California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Assistant Chief Kirk Barnett, his vacation payout of $578,000 last year was worth three years of his salary, according to payroll records. Barnett, who worked three decades for Cal Fire, could not be reached for comment.

Prison psychologist Victor Jordan retired in 2023 with more than $530,000 in unused leave time — the top amount paid that year. The payout was 2.8 times his salary.

Jordan said he worked around the clock at California Institution for Men in Chino, especially during the pandemic, but that his leave balance grew steadily over his three decades with the state. He said by the time he cashed out his unused leave, he still had days off from a 1992 cost-cutting plan that balanced the state budget by reducing salaries in exchange for additional days off.

“I had hours sitting on the books for 30 years,” he said. “For me, it was a perk. … A state job with the benefits, that’s why I was there. I had job offers for better money, but I wanted the retirement. I wasn’t even thinking about the [vacation] cash-out.”

Jordan said he once was chastised for booking a long vacation, but for the most part he didn’t take much time off because he provided a vital service to inmates. He said his phone never stopped ringing during his career, including in the middle of the night.

“I’d go in there and I dealt with it because I was really so thankful of the benefits,” said Jordan, who now lives in Nevada.

He said he knew his unused vacation would be a lot, but estimated it would be around $220,000. Despite the high taxes he had to pay on the lump-sum check, he said he still can’t believe how much it totaled.

“I didn’t know it was going to be this much,” he said. “It was shocking.”

When retiring employees leave, it’s not just the time off they have on the books that is part of their payout calculation. They are also paid for any additional time they would have earned if they had taken the days off instead. For example, an employee with 640 hours of leave is paid for additional vacation time and holidays they would have earned had they taken those 80 days off.

Each hour of leave is paid based on an employee’s final salary — not what they were earning when the time was accrued.

Mike Genest, who served as budget director for former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, said that meant that when he left state service, the vacation time he earned as a newly hired employee making around $17,000 was paid out based on his final salary of $175,000 in 2009.

Genest said while the current system is “fiscally irresponsible,” attempts to overhaul how vacation is earned or paid out would be “extremely unpopular.” Any changes would have to be negotiated with the state’s powerful and deep-pocketed public-sector unions, which are among the top donors to Democratic lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“That’s theoretically possible. It’s not politically possible,” he said.

Genest said he retired in 2009 with $37,000 in unused leave time.

“I’ve been in high-profile positions where getting a vacation in is tough,” he said.

But he said the price tag on stockpiled vacations today is simply unsustainable. If a retiring employee instead decided to burn down their vacation before leaving state service, they would receive their salary during that time including any raises their union negotiated, and the added time would count toward their pension.

“This shouldn’t be happening,” Genest said. “It’s bad budgeting. It’s bad practice.”

In New York, state employees can accrue a maximum of only 40 days of vacation, and when they retire, the payout for unused time is capped at 30 days. The state’s estimated liability for unused vacations was $1.1 billion as of March 2024, according to its annual financial report.

Texas state workers are also limited on how much vacation time can be carried over from one fiscal year to the next, with unused time off converted to sick days. The maximum amount of vacation for someone with more than 35 years of state service is 532 hours, or 66.5 days for those working eight-hour shifts, according to Texas state statute. The state’s liability for vacation time on the books for current employees is $1.2 billion, according to the state’s annual financial report.

California’s banked time could be a budget-breaker in a recession. The legally obligated payouts for unused time off wouldn’t pause, instead dealing a blow to dwindling budgets at state departments. Under state law, once vacation or other earned time off is accrued, it’s considered compensation and must be used or cashed out when an employee leaves, according to the California Department of Industrial Relations.

“It is on our mind because the balances have a value and the value grows over time,” said Eraina Ortega, director of the California Department of Human Resources. “So, we do think about it in terms of the financial liability of it being a growing problem with each year as compensation increases.”

For example, Soohoo, the prison supervising dentist paid $1.2 million for unused time off, saw his lump-sum payment increase by roughly $55,000 following a pay bump last year. Soohoo, who could not be reached for comment, retired in March with a $263,000 pension after three decades with the state.

Ortega said balances grew during the pandemic as workers — and the rest of America — weren’t able to travel as easily for vacation. At the same time, the state balanced its budget shortfall in 2020 by reducing employee pay in exchange for two extra personal leave days a month.

The nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated the added days off at a time when people weren’t taking vacations increased the state’s unfunded liability for leave balances by hundreds of millions of dollars.

Some departments have offered workers a chance to cash out up to 80 hours of their unused time off in hopes of reducing the liability of larger payouts when workers retire at a higher salary. Between 2021 and 2023, the state’s vacation buyback program paid employees $288 million for unused hours. The program wasn’t offered last year amid a worsening budget outlook.

Beginning in 2022, Ortega said, the state started seeing more people using their vacation time. That trend could continue to improve with return-to-work orders, she said.

In March, Newsom issued an executive order requiring roughly 95,000 state workers to return to the office four days a week beginning July 1. The remainder of the state’s workforce was already in positions that require in-person work, such as prison staff, Highway Patrol officers and janitors.

Managers are supposed to have employees over the vacation cap create plans to reduce their saved time off, but Ortega concedes that those aren’t always followed and enforcement is “not uniformly implemented across all the departments.”

She said encouraging employees to take vacation time is not just about the financial liability to the state. It’s about “the health of our workforce.”

“That’s part of why we have vacation time,” she said. “You want people to take breaks and be refreshed.”

Jordan, the retired prison psychologist, said taking time off can be hard to do at times, especially for people working essential jobs.

“You start to earn so much vacation that there’s only so much you can take,” he said.