In addition to Nigeria’s northern region, many nomadic communities down south lack functional schools. School-age children idle around their huts all day.

Where nomadic schools exist in the Iseyin town of Oyo state, southwestern Nigeria, just 62 miles north of Ibadan, the state capital, they lack critical infrastructure and sanitation, making them unfit to be called a place of learning for the young ones.

This is the case with Nomadic Primary School (NPS) Ajiwogbo, a nomadic primary school that tells of resilience draped in neglect.

There, a single dilapidated building struggles to hold its purpose. Its corrugated roof dulls under the sun, offering meagre shelter from the elements. Flies buzz relentlessly as bees would in an almost deafening hum of discomfort. The pupils swat them off their faces, barely distracted from the lessons happening inside.

Cow dung litters the surrounding pathways, a stark reminder of the livestock mingling freely with students on the premises. The air is thick with the acrid smell of waste and earth.

Barefoot children, many with patched clothes and moisturised skin, sit in these crude conditions with wide, curious eyes. They hold onto stubby pencils and frayed notebooks, determined to extract a future from the fragments of opportunity around them.

The absence of infrastructure — a proper floor, classroom furniture, windows, or sanitation facilities — speaks volumes of their reality, where education, though meagre, is a hard-won pursuit.

“We don’t have sufficient classrooms. We use two, despite needing at least six,” A.F Olalekan, the school’s assistant headmistress, explained to TheCable during a visit. “We had to mix the students.”

NPS Ajiwogbo also recorded low enrollment despite the high population of nomads in the community. Olalekan narrated how door-to-door visits upped the school’s student population from 30 to over 100.

“We need more nomadic children to return to school to be useful within the community. The government must undertake awareness campaigns targeting nomadic parents,” the head teacher said.

Some 39 kilometres from Ajiwogbo is Ilero, a settlement where Muhammed Usman, a father of eight, lives without a school to enrol his children.

“We have engaged in a series of meetings with the government but got no help. During the electioneering season, they promised to build us schools. To date, they have not fulfilled their promises,” he lamented.

Yakubu Bello, a traditional chief who looks out for the interest of the Fulbe community in Oyo, noted that most nomads in remote communities lack access to adequate facilities to enable their education.

“The ones close to town join conventional schools. For those in the bush, however, it is either a nomadic school or no school at all. A lot of nomadic children are supposed to be schooling but are not,” he said.

Umar Ardo, director of extension education at the National Commission of Nomadic Education (NCNE), said at least ₦12 billion in consistent annual capital funding is needed over the space of five years to address its infrastructure deficits, with a 15 to 20 per cent yearly increase to hedge against inflation and the rising demands of nomadic education.

Budget analysis revealed the NCNE was allocated a cumulative ₦2.29 billion for construction projects within a five-year window of 2020 to 2024. A stand-out case was in 2024 when ₦1.33 billion was set aside for this purpose, a large chunk of which serviced ongoing projects not directly related to classrooms or schools. Within this window, ₦1.14 billion was budgeted and allocated for repairs and rehabilitation.

Nomadic schools face severe teacher attrition

Umar Ardo said tutor attrition is extremely high in nomadic schools. He said many state-hired teachers trained with NCNE resources lobby relentlessly to transfer and relocate away from rural areas partly due to the nonpayment of hardship allowance by the state basic school boards.

He said this has forced NCNE to rely heavily on signing bonds with the local governments to ensure that the commission’s limited teachers remain in their assigned nomadic schools for at least a stipulated number of years before reassignment.

“Teachers have the right to in-service training that requires moving. In insecure areas, you can’t guarantee safety. No law mandates them to remain there for life. And you can only beg, not recruit,” he explained.

In Kaduna, Musa Ibrahim Aboki, the state universal basic education board’s assistant director for access and equity, said the agency is looking to work with local government education departments to perfect the recruitment of 10,000 teachers, some of whom are expected to be nomadic.

Ibrahim Bayero, the Kaduna media director of the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria, said such recruitments are usually not enough to serve even the conventional public schools, talk more of nomadic.

“Nomadic schools are neglected. Very few are co-opted by the state to be sent teachers. The State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) is not giving nomadic schools the attention they deserve,” Bayero raged in a phone interview.

On the national scale, Umar Ardo had similar concerns: “Most of those deployed to nomadic schools from states and local governments are low-quality teachers who are not wanted in conventional schools. They are sent as either punishment or replacement.

There is an incessant transfer of trained teachers from nomadic to conventional schools. We spend a lot of time training them on nomadic pedagogy. But they look for posting and return to conventional schools.”

Northwest Nigeria has had a history of violent farmer-herder conflicts driven by the tussle for land and water resources, slowly yielding a network of terrorism that would come to be popularly known as “banditry”. But analysts say what served to catalyse terrorism in Nigeria over a decade ago may no longer solely be what drives it now.

Poverty and limited economic opportunities increasingly forced marginalised people into joining terror groups as a means of survival. Inadequate government presence and law enforcement in remote rural communities created a vacuum that the terrorists exploited.

The proliferation of small arms escalated the intensity and frequency of terror attacks, with a changing climate and stretching deserts worsening resource scarcity. Cattle rustling and abduction for ransom became lucrative, resulting in a cycle of almost never-ending blood spills, reprisal attacks, and migration.

Multiple reports indicate that this ‘bandit’ culture has spread beyond the northwest, affecting Taraba and Adamawa states, where it overlaps with insurgency in the north-east as well as Oyo, Ondo, Ogun, and Ekiti in the south-west.

Terrorism is a composite crime that includes abduction, massacre, rape, cattle rustling, firearms possession, and even illegal mining.

NBS data, as of 2022, shows the north-west had the highest poverty rate in Nigeria, with some 45.49 million people (75.8 per cent of the population) living in multidimensional poverty. States like Zamfara, Katsina, Kaduna, and Sokoto have had security hotspots where entire local governments are reportedly overrun, and residents, including children, unwittingly mingle with terrorists.

The CDD gives an admittedly tenuous estimate of at least 100 terror groups operating in the northwest alone, constituting between 10,000 and 30,000 armed militants.

According to an IPI report, their activities have devastated communities with an aggregated 1,087,875 rural dwellers displaced as of 2022. Schools are often forced to shut down from the tension, leaving impressionable young children and students without meaningful social preoccupation.

In 2024, Nigeria’s Senate President Godswill Akpabio warned that the country’s unschooled children of today risk becoming the terrorists of tomorrow.

Left on the margins of society and heavily dependent on adults, these young folks become vulnerable to recruitment into criminal activities that sadly offer an alternative sense of identity, protection, income, and power.

The Fulbe Education Awareness and Development Association, a non-profit, has been traversing disconnected nomadic communities in the north to revive dysfunctional schools and encourage child re-enrollment to avert this crisis.

“Many of our people get into banditry because they never had the opportunity to attend school,” said Hassan Lamido, the non-profit’s national secretary, who acknowledged the role of literacy in providing a pathway to inclusion, socioeconomic stability, and upward mobility for the nomads.

He affirmed: “Some young nomadic children are joining bandits because they lack access to education.”

Lamido cited a part of the Giwa LGA in Kaduna where he said children are “prone to commit to terrorists groups” and even their uneducated “parents are not stopping them”.

“In Birnin Gwari and Chikun LGA of Kaduna also, it is happening. In Zamfara, Sokoto, and Birnin Kebbi, especially around places with lots of vegetation, children join bandit groups because they are not meaningfully engaged,” Lamido said.

“Some of their elders are bandits, so they grow into it and think banditry is noble work.”

Husseini Abdullahi, a Fulbe disaster analyst and now the LGA vice-chair in Kachia Kaduna, said tracking and resettling displaced nomadic communities, relocating affected schools, and re-employing teachers is a capital-intensive project Nigeria must undertake only after the scourge of banditry has been significantly neutralised. The latter, he said, must start by cutting off the illegal influx of small arms.

Nigeria’s creation of a livestock ministry, Abdullahi added, could ensure that nomad resettlement is prioritised. At the same time, a census can then be conducted to systemically capture nomadic populations in social interventions and secure the future generation of nomads from looming crises.

Legislative delays hold back urgent reforms

The legislation that guides the National Commission for Nomadic Education was introduced in 1989 under the late military leader Ibrahim Babangida’s regime and codified into Nigeria’s civilian laws by 2004. However, it has remained unchanged for 35 years despite the evolving needs of nomadic populations.

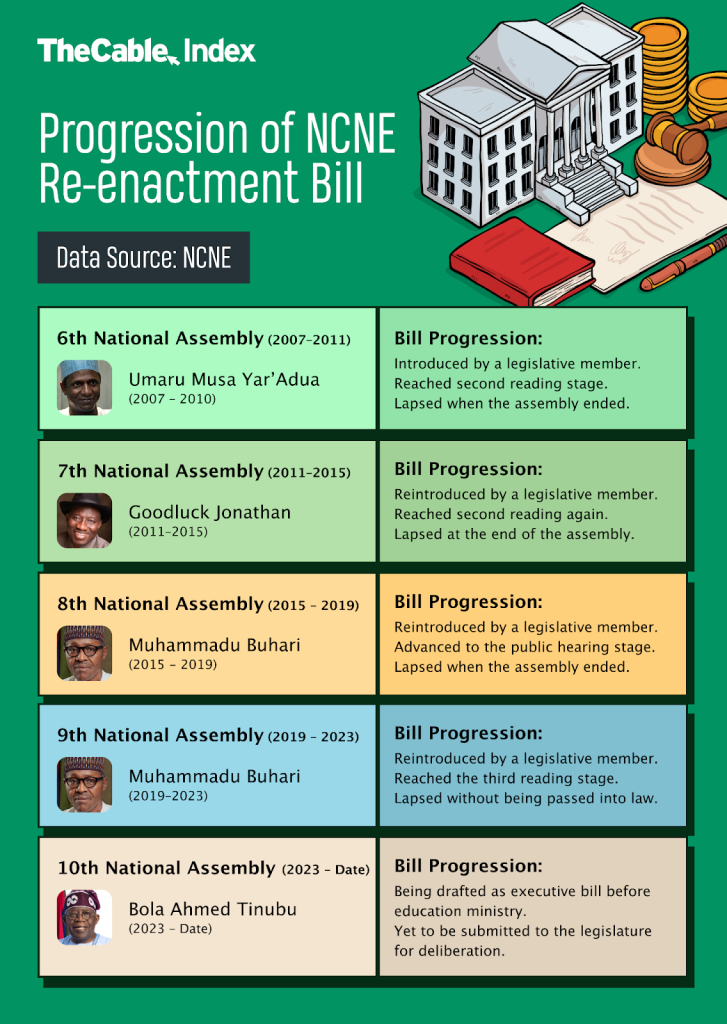

Efforts to re-enact this legislation have repeatedly stalled.

Legislative member bills proposing critical amendments to address the commission’s apparent funding deficits and teacher attrition troubles have failed to progress beyond the second reading in multiple national assemblies — ending at this stage during the sixth and seventh assemblies, reaching the public hearing stage during the eighth, and once again stalling at the second reading in the ninth.

Each failure has forced the process to restart from the draft with subsequent assemblies, illustrating the challenges of pushing through member-sponsored legislation.

In the tenth assembly, the re-enactment is taking a new path as an executive bill being drafted at the education ministry and undergoing reviews involving its legal department and the ministry of justice. This is intended to guarantee political, technical, and legal backing that could enable faster processing.

Submission to the legislature is anticipated by the end of the first quarter of 2025, following approval by the federal executive council.

By convention, Nigeria’s public school teachers are hired, owned, managed, and deployed by local governments who work closely with state basic education boards. Many of these conventional teachers will then be retrained to adapt their methods to the nomadic curriculum.

The proposed NCNE amendments aim to empower the commission to hire mobile and non-mobile teachers independently without relying on state universal basic education boards, ensuring seamless cross-border operations for mobile teachers who serve actively migrating nomadic communities.

The bill also seeks to establish a Nomadic Education Fund designed to stabilise funding through diverse revenue sources, including non-profit donations and foreign aid, managed by a dedicated board of trustees.

Additionally, the NCNE advocates state-level nomadic education departments with independent budgets to bolster financing and ensure comprehensive coverage, recognising that basic education is on the concurrent list with responsibilities for not just federal but also state governments.

It seeks a statutory percentage from the Universal Basic Education Commission’s two per cent cut of the consolidated revenue fund, a pool into which taxes, duties, fees, and other federal revenues are deposited for onward disbursement.

Whatever the bill’s fate, the prolonged legislative delays condemn nomadic children to an uncertain future, robbing them of the education they need to escape cycles of poverty and crime.

Nomadic schools remain unsafe

In 2015, Norway and Argentina led a process among UN member states to develop a political agreement that would become the Safe Schools Declaration (SSD). A total of 120 countries, including Nigeria, endorsed the guidelines of this pact. In 2019, Nigeria ratified the SSD, effectively committing to protecting students, teachers, and schools during conflict to guarantee the continuation of education.

The SSD holds that schools must remain safe havens during armed conflict or insecurity.

In the context of terrorism by non-state actors, this implies implementing measures to prevent the targeting of schools or the abduction of children. For nomadic schools, it includes securing learning spaces to ensure they are not abandoned due to fear of violence.

SSD guidelines mandate the creation of contingency plans for securing education during crises. For nomadic communities, this could take the form of deploying mobile security units, early warning systems, or community-led initiatives to protect schools, teachers, and learners.

The SSD recommends support for children affected by attacks. For nomadic children traumatised by terrorism or abduction, policy experts argue that mental health programmes and reintegration services would ensure they can continue education in a supportive environment.

SSD encourages governments to work with international organisations, non-profits, and communities in addressing education-related challenges. For Nigeria, this means leveraging partnerships to adopt and adapt innovative education models such as mobile schools.

In 2022, a finance plan for the Safe School Initiative (SSI) was launched, outlining investment totalling ₦144.8 billion over a four-year term to protect 62,271 at-risk schools and their learners, teachers, and nonteaching staff from attacks.

Nigeria was to spend ₦32.58 billion in 2023, ₦36.98 billion in 2024, ₦37.15 billion in 2025, and ₦38.03 billion in 2026. But budget funding has not materialised as planned, with the government setting aside a comparatively paltry ₦15 billion in 2023 and ₦5.01 billion in 2024 for the SSI. Budget analysis for both years also showed no structured and holistic funding for projects related to the SSI.

So, while the SSI laid a strong groundwork for safer learning environments, its uneven and inconsistent implementation has left many public schools, more so those serving nomadic populations, vulnerable to ongoing threats. As a result, the low-hanging response by states to persisting attacks and student abductions was to close those schools.

Badar Musa worked with Nigeria’s education ministry and the Education in Emergencies Working Group, a coalition of government stakeholders, the UN, multinational non-profits, and other stakeholders. He participated in projects that informed Nigeria’s policies around safe schools before joining Save The Children International’s office in Nigeria as an advocacy campaign and policy manager.

Musa said Nigeria tapped the newfound SSI funding in February 2023 to create a national safe schools coordination centre domiciled at the headquarters of the National Safety and Civil Defense Corps (NSCDC), where all Nigerian security agencies and MDAs are represented.

“By 2024, the centre had prevented 86 attacks on education nationwide. If it gets intelligence about impending attacks, the HQ alerts relevant security agencies around the threatened location,” he said.

“The centre is still registering all schools in Nigeria on their database with precise coordinates and contact persons. About 11,000 schools have been registered.”

In 2024, UNICEF analysed the implementation of Nigeria’s minimum standards for safe schools, which guides the domestication of the SSD, across a sample of states in the northwest and northeast. The agency reported a “minimal implementation rate” with an average score of 42 per cent as of 2023. Its findings concluded that “a significant gap between policy formulation and its execution” persists.

“Education has deteriorated. Nomadic education is at a higher disadvantage because it is non-formal, which is underfunded. If we can’t protect non-formal schools, how much more the ones located in coordinated environments?” said Musa over a video conference.

Nigeria is desperate to cut its alarming out-of-school children rate, integrate informal schooling into formal systems, and work out an accelerated basic education scheme for over-age underserved people in a scramble to score more positive development indices.

Yet, an observation of grassroots realities indicates that nomadic children remain no more than an afterthought.