Whenever the subject of trade comes up, many right-leaning free traders and left-leaning neoliberals alike trot out the same talking point: “The economists all agree tariffs are terrible!” And perhaps they do — or at least most of them do. Barriers to free and unfettered trade may well appear inefficient as a matter of an economic model’s deadweight loss — and they may well conflict with David Ricardo’s much-heralded 19th century trade theory of comparative advantage. It may well be the case that consumer surplus is indeed harmed by restrictions on the free flow of goods.

But this is classroom theory. And the “dismal science” that is the economics profession is not always known for its close relationship to, well, real life.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, elites of both parties in the U.S., overly confident in their conviction that Western openness had just defeated the Soviet “Evil Empire,” rushed to implement a Washington Consensus of globalization and trade liberalization — on all kinds of products, ending selective Reagan-era trade barriers to, for instance, Japanese cars. An advisor to President George H.W. Bush memorably quipped in 1990: “Potato chips, semiconductor chips, what is the difference? They are all chips.”

But that’s economic theory, not real life. The reality is there is a tremendous difference: The U.S. wouldn’t be dragged into a war to protect our access to potato chips, as we might be to defend the world’s leading supplier of semiconductors, Taiwan, if China invaded.

More generally: It is certainly true that free and unfettered trade lowers prices for consumers and thereby maximizes consumption. And in contemporary post-Berlin Wall consumption-based Western economies, it can be easy to lose sight of other concerns of economic statecraft. But there are other concerns: namely, production and supply chain resilience.

Great Americans have understood this at least as far back as Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 “Report on Manufactures,” in which he argued that free trade is often an illusion: “If the system of perfect liberty to industry and commerce were the prevailing system of nations, the arguments which dissuade a country in the predicament of the United States from the zealous pursuit of manufactures would doubtless have great force. … But the system which has been mentioned is far from characterizing the general policy of nations.” Abraham Lincoln, who decades later would become the Republican Party’s first president, took a similar stance in an early-career 1832 speech: “My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank. I am in favor of the internal improvements system and a higher protective tariff.”

In many ways, that Hamiltonian/Lincolnian impulse helped America become an industrial powerhouse. It was that same manufacturing powerhouse that defeated both the 19th century Confederate insurrection and the 20th century Nazi war machine.

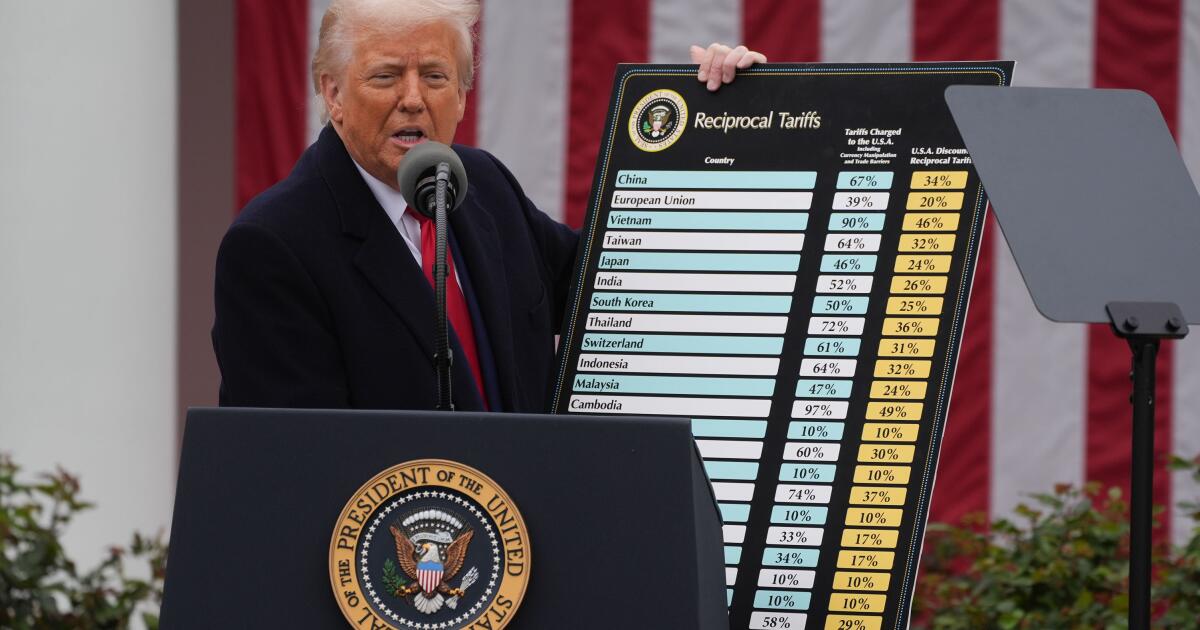

It is that noble impulse that seems, in the year 2025, to motivate President Trump as he embarks upon the most aggressive tariff campaign the nation has seen in decades. Investors, invariably in thrall to classroom theory, have reacted poorly. But this experiment has just begun; the jury is still out.

Truth be told, we may not know the full effects for years. But already, there have been at least some positive signs that Trump’s promised approach has been working. In February, Apple — the largest company in the world by market capitalization — announced it would invest $500 billion in the U.S. over the next four years. Johnson & Johnson has pledged $55 billion in U.S. investment, and Nvidia allegedly plans to invest “several hundred billion” dollars in electronics manufacturing. Other recent examples abound, and we should expect the trend to continue.

That is not to say that all is fine with the Trump tariff rollout, though. The tariffs unveiled thus far in this second term, culminating in Wednesday’s “Liberation Day” Rose Garden speech, are directionally correct but markedly over-inclusive. There is a tremendous difference between slapping punitive tariffs on China and Canada. China has robbed America every which way for four decades, and we are far too economically dependent on the nation that is also our top geopolitical threat this century. But what is the issue with our friendly northerly neighbor, exactly? If anything, Trump’s tariffs on Canada — combined with the recurrent reckless talk of annexation — seem to have caused the political collapse of Canada’s Conservative Party on the precipice of a crucial national election.

There is also the issue of consistency. The administration’s tariff rollout has given off the distinct impression of being done in a scattershot, shoot-from-the-hip manner. Markets value stability and predictability — and it is likely the instability or unpredictability of the tariff policy, even more so than the tariffs themselves, that has spooked so many on Wall Street.

Americans don’t elect economists as our leaders to monolithically pursue the most “efficient” policies possible. And thank goodness for that. Instead, we elect leaders who will exercise prudence, discernment and sound judgment to pursue the common good. Tariffs absolutely do have a role to play. But while a thunderous jackhammer of a policy disruption may be appealing, sometimes a mere scalpel will suffice.

Josh Hammer’s latest book is “Israel and Civilization: The Fate of the Jewish Nation and the Destiny of the West.” This article was produced in collaboration with Creators Syndicate. @josh_hammer