The artist, an Oklahoma transplant, was instrumental in establishing the lively Los Angeles art scene of the 1960s

Visual image and material object are held in equipoise in Goode’s paintings, which range from milk bottles on the front stoop to clouds floating overhead in azure skies.

Is a painting an image or an object? Or reverse the order for a sculpture — is it an object or an image?

It’s both, Joe Goode’s art answered as the 1960s began — something surely material but purely visual. And something else besides, something curious and engaging that you haven’t ever seen before. In his strongest work, the Los Angeles-based artist — who died of natural causes in his sleep on March 22, a day before his 88th birthday — held the image and the object in eccentric equipoise. The result is an uncanny sense of vivid presence.

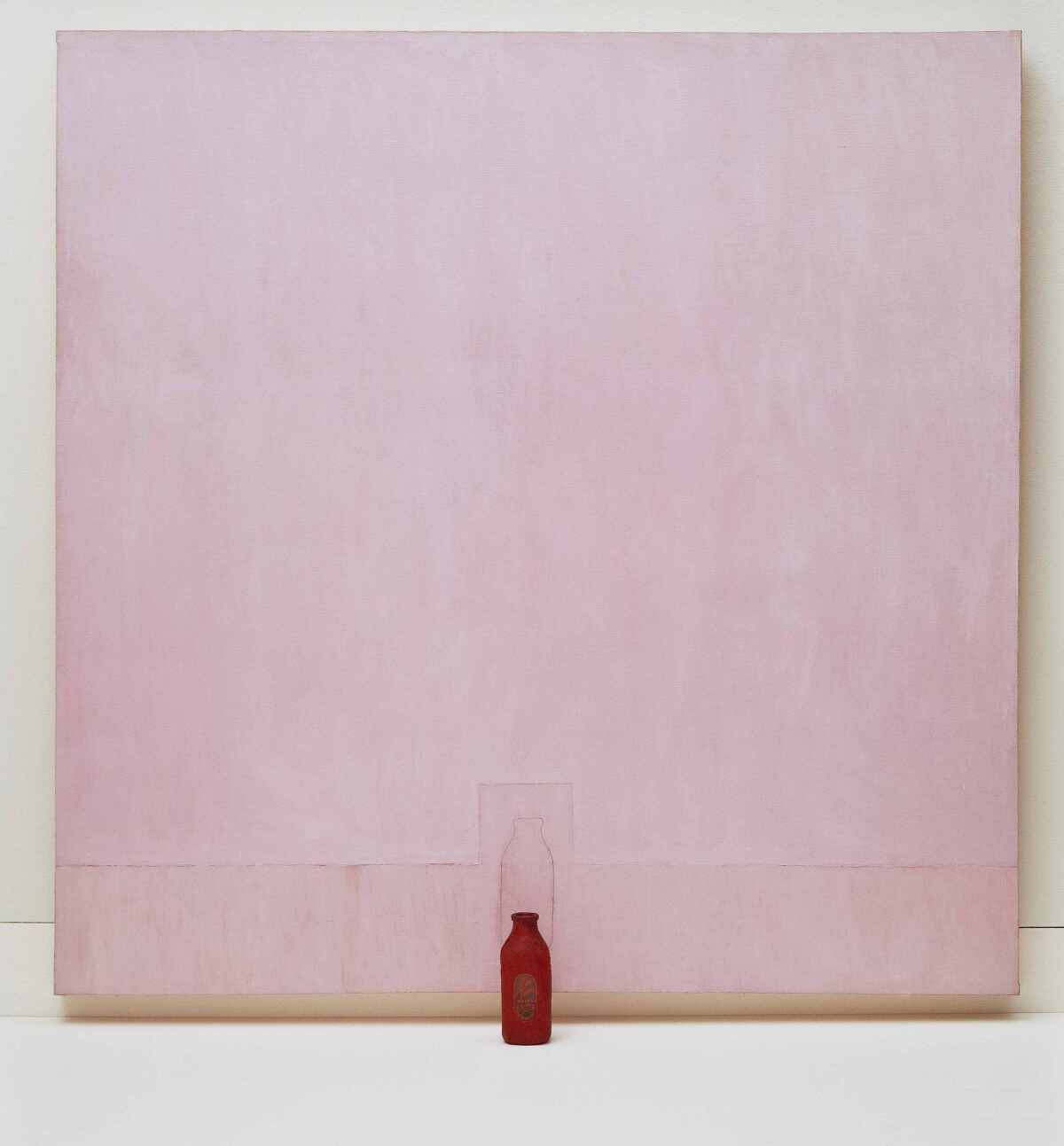

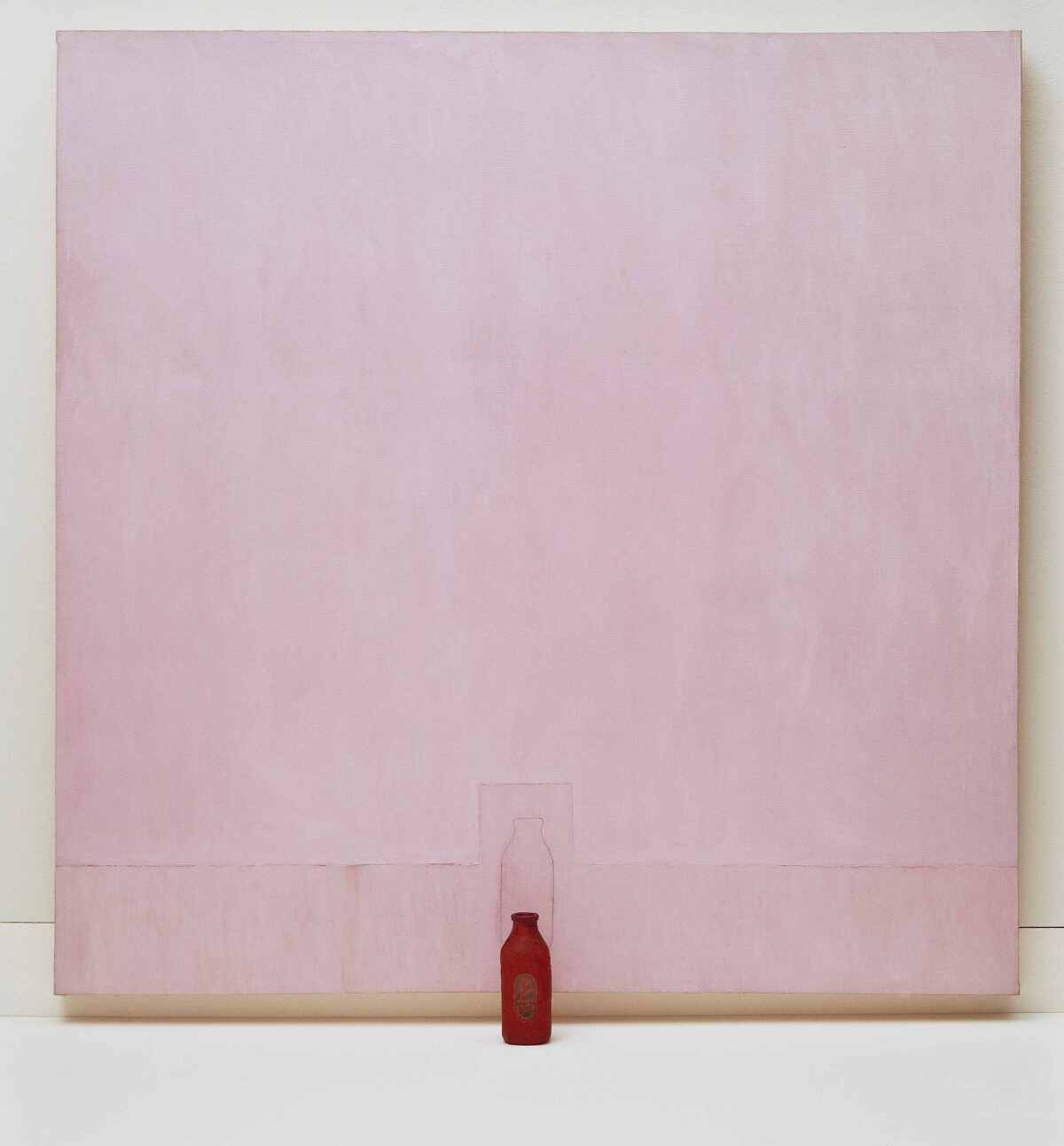

In 1961, not long after the Oklahoma transplant left Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), where he studied with influential Light & Space artist Robert Irwin, Goode began an enigmatic series of 13 paintings of milk bottles. Most are roughly square, five-to-six foot canvases of seemingly monochrome color.

Joe Goode, “Happy Birthday,” 1962, mixed media

(San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

A glass milk bottle from Alta Dena Dairy slathered with paint, either in matching or contrasting color, stands on the floor in front of the painting, which is hung about three inches off the floor — certainly an unusual height. Installed that low, the painting’s scale is geared to the body of an average adult looking at it. The flat painting becomes a “wall,” the slathered milk bottle becomes “a painting.”

Sometimes, Goode included a contour drawing of the bottle behind it on the canvas, suggesting that one is the projection of the other. (Whether the bottle or the painting is the projection remains a question.) Look closely, and often the monochrome canvas is gently brushed with multiple layers of color. The result is ethereal, further enhancing the image/object conundrum.

Goode’s knockout series arose from two primary sources. One was the contemplative, nearly monochrome still lifes of ceramic vessels by heralded Italian artist Giorgio Morandi, which caused a stir in 1961 at the painter’s rare American gallery exhibition at Ferus on La Cienega Blvd. The other was the vigorous argument between abstraction and figuration as front runner of the avant-garde, then being hard-fought in the American art world. Which was more adventurous? Goode’s painterly retort — still lifes that held the abstract and the figurative in taut equilibrium — brilliantly neutralized that argument, while adding depth to the object/image dichotomy.

A third, less observable source was more private and personal: When Goode’s first child was born, the milkman arrived at the doorstep almost daily bearing a fresh Alta Dena bottle. The artist launched the series. Art’s spur came not only from the specialized art world, but from ordinary human experience. Goode’s job was to bring them all into harmonious play. One work, a deep purple monochrome rising behind a vivid orange bottle, graced the sixth cover of the new Artforum magazine.

In the 1960s, Goode’s work was uncomfortably tagged as Pop art. It shared some attributes of paintings by Ed Ruscha, his childhood friend from Oklahoma City, as well as Southern California artists as diverse as John Baldessari, Billy Al Bengston, Wallace Berman and Vija Celmins, with whom he established the vigorous 1960s L.A. art scene. But those artists approached representational imagery in a wide variety of ways. As his career developed over the next five decades, and as art movements began to unravel as a way to characterize art, the term fell away.

Joe Goode, “Untitled,” circa 1968, wood and carpet

(Museum of Contemporary Art)

Goode almost always worked in a series — for instance, making multiple sculptures of staircases whose orderly repetition of rectilinear treads and risers put a domestic tongue firmly in the industrial cheek of Minimalist art’s crisp geometry. (Carpeting softened the cold edges.) He hung painted paper and canvas on a line and blasted them with shotgun pellets, the random shredding establishing layers of color when the sheets were placed atop one another, or exposing the gallery wall as yet another painted layer. He painted clouds drifting through azure skies, then tore them up and reassembled the heavens to his liking. He splashed and poured liquid thinners over paint, causing chemical reactions to burn holes in the surface — “Ozone Paintings,” he called them.

Creative destruction was a regular theme. (Even in high school art class, Goode had delighted in making sculptures to be set on fire.) An element of violence was appropriate for an era torn apart by war, civil rights unrest and epic environmental degradation, but Goode redeemed the tumult through art.

One result was an extensive exhibition record — more than 120 solo shows at museums and galleries internationally – as well as representation in nearly 30 museum collections, including extensive holdings at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Goode is survived by his wife, Hiromi, and niece Yuki Katayama. No funeral for the artist is planned, but according to a spokesman at Michael Kohn Gallery, which represents the artist, a memorial celebration is being discussed for a later date.