Joe Biden was the first president to join a union picket line and support labor’s side in a number of major disputes. His appointments to the National Labor Relations Board, the principal administrative agency handling labor-management conflict, interpreted the 90-year old National Labor Relations Act so as to enhance the rights of workers to organize. The Biden board promoted workplace democracy more effectively than any of its predecessors.

As the saying goes, no good deed goes unpunished.

President Trump’s second term presages the most anti-labor labor board appointees ever (his first-term NLRB had that same distinction). And equally or more troublesome, Trump, through his arbitrary dismissal of Biden-appointed board member Gwynne Wilcox has joined a position advanced by management labor lawyers at Starbucks, Trader Joe’s and Elon Musk’s Space X, among others. Together they wish to take a wrecking ball to labor law, asserting that the 90-year-old National Labor Relations Act and the independent agency it established are unconstitutional.

On March 6, in a sweeping opinion both eloquent and scholarly, U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell pushed back against the president’s unlawful firing of Wilcox. Now, as was surely the plan all along, the question of control of the NLRB can and will go to the Supreme Court. If the conservative, Trump-appointed majority agrees with the president — instead of upholding nearly a century of precedent — independent due process for labor and management will be wiped away.

Of course, politics and labor law have always had an uneasy coexistence. By virtue of the National Labor Relations Act’s system of five-year staggered appointments to the NLRB, presidents are able to influence the board’s direction during their four-year terms, but they cannot dominate it or dictate the outcome of a particular case that is before the labor board.

If, however, board members can be dismissed by a president any time he or she disagrees with their votes on the reinstatement of a dismissed worker, say, or a conclusion that labor or management has not bargained in good faith, the rule of law can easily be denied, along with well-accepted principles of independent conflict resolution.

Such a prospect is an ominous cloud over a labor movement that even during the friendly Biden era lost ground. Today unions represent only 11.1% of employees in the workforce. Does all of this mean that organized labor law is a doomed dinosaur, irrevocably headed toward irrelevance? Not necessarily.

First, as important as legal protections have been to organizing, law has proved to be a subordinate factor in union growth or decline. In the 1930s, union militancy was in place at least four years before the National Labor Relations Act became effective. The 1947 Taft-Hartley amendments to the act placed restrictions on unions and workers, yet unions continued to grow for nearly a decade after its enactment. Labor won considerably more of its workplace elections in the George W. Bush era than under a more pro-labor board during the Obama administration.

As important, according to U.S. Labor Department data, unions hold $42 billion in financial assets. They can use these monies to finance costly and protracted campaigns in many different businesses, hiring dedicated workers who will give their wholehearted attention to the difficult, time-consuming work of organizing. And these positions could be made more attractive by the promise of advancement to union leadership positions, now too often the province of those who process membership grievances rather than working to widen unions’ reach.

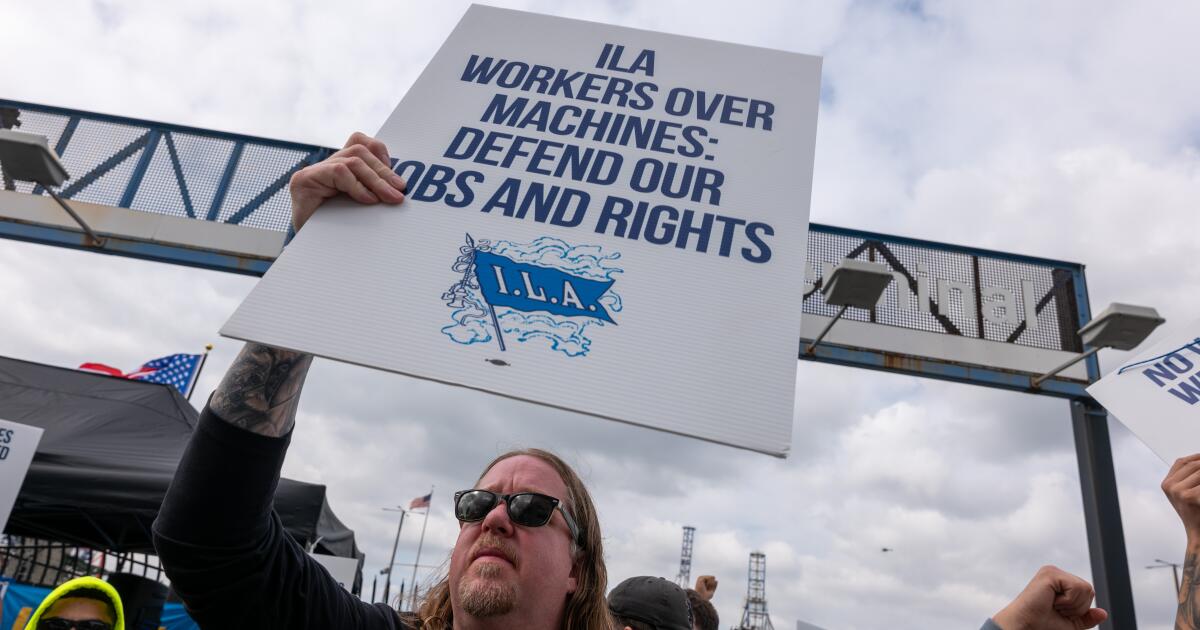

The stage has been set for just such organizing, with recent effective uses of the strike weapon. In 2023, the United Auto Workers new rolling strike strategy against the Big 3 auto companies produced substantial wage and benefit increases. In January, the International Longshoremen’s Assn. obtained more than a 60% pay increase over six years, plus an apparent ban on automation, on the basis of a short stoppage last fall at ports on the East and Gulf coasts.

Further, if Trump is even partially successful in his attempt to rid the country of immigrants, a result will be a shortage of workers, which will slant the labor market toward the sellers. The impact in construction, for instance, a sector that is already short hundreds of thousands of hires, will only improve the prospects for unions.

And lastly, if the Supreme Court uses Wilcox’s case to deem the National Labor Relations Act and an independent NLRB unconstitutional, or contrives to consign them to irrelevance, states such as New York, California, Michigan, Illinois and others can work to occupy the vacuum with more robust labor legislation.

The fight is not over.

William B. Gould IV , a professor of law emeritus at Stanford Law and chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, is the author of “Those Who Travail and Are Heavy Laden: Memoir of a Labor Lawyer.”