In a year in which the hometown team is the defending World Series champion, its manager stopped by one afternoon to visit with the high school baseball team.

The national media took note. The neighborhood newspaper chronicled the event. Photographs spread rapidly across social media.

However, on the day the Dodgers’ Dave Roberts delivered his pep talk to the Palisades High baseball team, the school newspaper was not there to cover it.

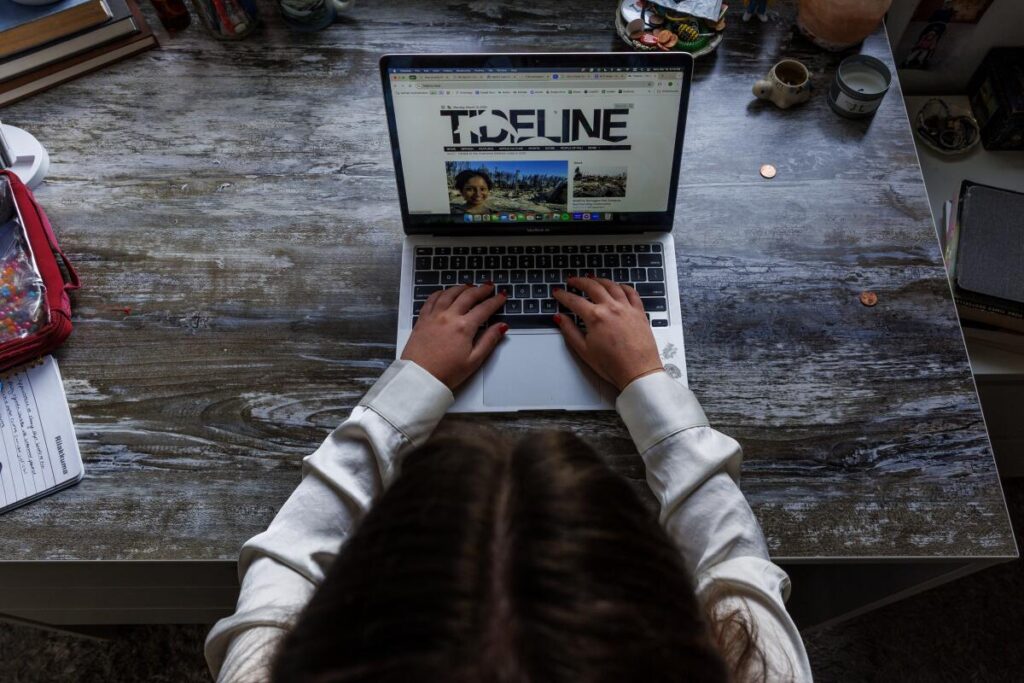

The staffers of the Tideline — the student newspaper at Palisades Charter High School — are living through the story of their lives. The Palisades wildfire destroyed their newsroom, damaged the school and decimated the surrounding village.

The Dave Roberts story would have to wait. There were more urgent stories to tell.

Cloe Nourparvar works on the student newspaper at Palisades Charter High School.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Two weeks after the fire first roared, with the school closed indefinitely and classes shifted to Zoom, the Tideline staff met for its first planning meeting of the new semester. The co-sports editor delivered a heartfelt farewell; he had enrolled in another school. Three other journalism students left too.

One Tideline staffer moved in temporarily with Cloe Nourparvar, one of three editors in chief. Audrey Smith, the managing editor, shuffled with her family from one hotel to another, then to a home in the Coachella Valley for a week, and most recently to an Airbnb property.

“We have it for a month,” Smith said in an interview, “and then we’ll probably move again.”

As the classes moved online, the classwork did not stop. For the Tideline staffers, neither did the reporting on so many vital questions: Would classes resume in person and, if so, where? What happened to all the teachers displaced by the fire? Where would Pali’s athletic teams play their home games?

In the weeks to come, the Tideline would post headlines from a reality far removed from homecoming games and student awards:

Wildfire Damages Pali Campus, Surrounding Community

Price Gouging in Rental Market Hits Home in Wake of Wildfires

Pali Strong: Student Organization Supports Fire-Recovery Efforts

“It’s never really been the case that we have too many stories and not enough writers,” Nourparvar said, “but that’s what it is right now.”

For the young journalists at Pali High, the fires present not just the challenge of reporting the facts. As in professional newsrooms, questions of ethics and sensitivity have arisen.

At that first staff meeting, the students faced this dilemma: Just before winter vacation, the Tideline had posted a satirical article about how no one on campus really paid attention to fire alarms.

This was the second paragraph: “ ‘Imagine if there was actually a fire,’ my desk partner giggled. ‘Nobody would even do anything.’ ”

Nineteen days after the article was posted, there was actually a fire. Should the student journalists alter the story in any way, leave it as is, or remove it from the website?

“I was a little worried about that satire being in bad taste,” one of the co-authors, Cole Sugarman, told his classmates on Zoom. “When I wrote it, I didn’t think the whole town would burn down.”

The journalism teacher at Pali had endured her own trying times. In 2014, Vice called her “the woman who helped change sports writing forever.”

In 1980, even before she had graduated from Cal State Northridge, the Los Angeles Daily News assigned Lisa Nehus Saxon to help out with its baseball coverage. From 1983 to 1987, the baseball beats were hers: first the Angels, then the Dodgers, then the Angels again.

It was not a cordial time for Nehus Saxon or the two other women covering major league beats. Players gave interviews in clubhouses, where women were not often wanted. Four teams barred her from their clubhouse. When she was admitted, harassment was prevalent. For every Tommy John that welcomed her, there was a Reggie Jackson that badgered her.

Lisa Nehus Saxon, advisor to the student newspaper, sits on a bench just outside the school campus, which has been closed due to damage from the Palisades fire.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“That’s probably why I’m handling the wildfire losses so well,” she said. “It’s not as though this is the worst thing that’s ever happened to me.”

Nehus Saxon subsequently covered the Raiders for the Long Beach Press-Telegram. At her last journalism job, for the Riverside Press-Enterprise, she befriended an administrator in the Los Angeles Unified School District who spent her fall Saturdays distributing statistics at USC football games.

“We were the only women in the press box who weren’t serving food,” Nehus Saxon said.

In 2001, after Nehus Saxon lost her job in staff layoffs, that administrator called. The transition to a teaching career had begun. In 2006, she landed at Pali.

On the day the fire broke out, she and her husband, Reed, a retired Associated Press photographer, had been celebrating winter break on a trip to Mexico. The hotel televisions carried KTLA, and Nehus Saxon watched her classroom burn from afar.

She later saw a picture on the front page of The Times, with the LAUSD superintendent standing at the top of a staircase.

“The top of the stairs, to the left, is U-102,” Nehus Saxon said. “Not anymore. But that was my classroom.”

Los Angeles schools Supt. Alberto Cavalho climbs up steps to nowhere, at what had been an entrance to a classroom building at Palisades Charter High.

(Howard Blume / Los Angeles Times)

Her home, within walking distance of Pali, still stands. The damage assessment is ongoing, and she may be unable to return home for a year or two. She teaches from a spare room in her sister’s house in Granada Hills.

Her resiliency is reflected in her students, who do not shy from a difficult story.

“They’re not interested in covering the bake sale or the blood drive,” she said.

Sugarman, the sports editor, emphasized getting it right, because he was disappointed that major media reports did not always do so. No, the entire school had not gone up in flames. No, the Pali students were not on campus the day the fire broke out.

“That kind of annoyed me,” he said.

Teacher Lisa Nehus Saxon views an empty dirt parcel where her classroom once stood. Her journalism students continue to edit and put out the Tideline remotely.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

As the Zoom staff meetings continued, the students debated how to report about the perception that people affected by the Palisades fire did not need financial support. In reality, 47% of Pali students are people of color and 26% are economically disadvantaged, according to data from U.S. News and World Report school rankings.

“The lack of empathy is absurd,” Nourparvar said. “Not everyone in the Palisades is rich.”

Nehus Saxon shared tips on how to find out what everyone wanted to know: Are we going back on campus this year, on any campus?

Tip 1: Ask teachers if they are transferring their own kids out of Pali. That might be a telling indication.

Tip 2: Review the agendas and attend the meetings of the school’s governing board to learn what options are under consideration.

Nourparvar cited one obstacle that every student journalist must learn to overcome, in a time of crisis or otherwise.

“The administration,” she said, “is notoriously difficult to get ahold of.”

The Dave Roberts story eventually got done. Smith, the managing editor, wrote it. Roberts had met with the baseball team in a park about 10 miles from campus, where the team practiced in the shadow of the Fox studio lot in Century City.

“It’s crazy,” Smith said. “That would probably be the biggest story I’ve ever written about.”

In the before times, she meant. In these times, she wrote two fire stories before she could get to the Roberts story, which was in itself a fire story. Roberts had comforted a team that could not play a home game because of a natural disaster.

Firefighters put out a hot spot at Palisades Charter High School on Jan. 7.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The fire stories kept on coming. The staff created a feature, People of Pali, where non-staffers could write about their own experiences in the fires. One wrote a poem.

The questions kept coming too. With Pali hoping to resume in-person classes next month at the old Sears building in Santa Monica, what happens to students who moved away from the Westside when they were displaced from their homes? What determines whether the spring graduation can be held at the Pali football field? How can the Tideline replace all the books, cameras, tablets and microphones lost when the journalism classroom burned?

Journalists are trained to be observers. They report on the story. They are not part of the story. The Tideline staffers found it difficult, and at times impossible, to distance themselves from the story.

Smith interviewed someone she knew, a student who was at one point trapped in a home surrounded by flames.

“He thought he might die,” she said. “It’s really hard reporting about it and trying to stay objective.”

So many fundraisers had sprouted that Tideline staffers looked into where the money would go in those efforts — to the school administration, certain programs, the student body, or perhaps someone not affiliated with the school at all?

The Raise Pali fundraiser is school-run. The Pali Strong fundraiser is student-run.

Palisades Charter High School is hoping to resume in-person classes next month at the old Sears building in Santa Monica.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

In other times, the Tideline might not have written about a fundraiser organized by one of the Tideline staffers, given the appearance of a conflict of interest. In this case, the Pali Strong story appeared, but with a disclaimer: The staffer involved in organizing the fundraiser “was not interviewed for this article.”

The Tideline staff edits every story as a class, so that everyone can learn. The proposed headline for the Pali Strong story started with these two words: “Students Trailblaze.”

As Nehus Saxon told the class gently: “I don’t know if we want ‘blaze’ in the headline.’ ”

That, in essence, explained how the Tideline decided to handle the satire about the fire alarms. There was nothing malicious in it. Since fire alarms often sounded when someone vaped in a school bathroom, who would pay attention when the alarm really did signal a fire?

“I’m not embarrassed by the story,” said Sugarman, the co-author. “I think it brought up good points. It wasn’t about fire mismanagement or brush clearance or anything like that.

“But it wasn’t what we wanted to project, considering whoever reads our website is going to be impacted: a funny story about a fire happening on campus, especially after part of the school burned down.”

The Times and other professional outlets rarely remove published stories. When circumstances arise, an editor’s note can be added to a story. The Tideline staffers considered that. There would come a time when professionalism would be the absolute priority, they decided, but this was not that time. They took the story down.

“We’re going to have some extra tact,” Nourparvar said, “when it comes to something that we feel heavily affects us or our friends.”