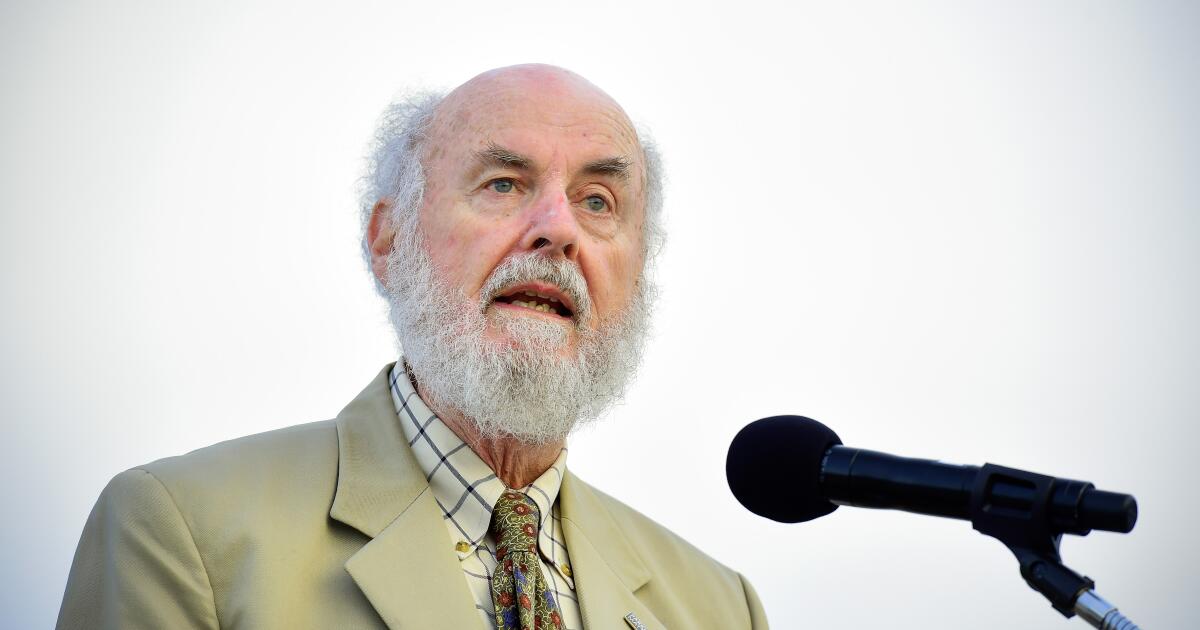

Over more than a half century of clear writing, clever quips and exhaustive scholarship, Donald Shoup became one of the world’s foremost experts and influencers on a topic seemingly as mundane as it is universal: parking.

Shoup, an economist and distinguished professor emeritus of urban planning at UCLA, died Feb. 6 after a brief illness. He was 86.

Shoup’s central argument, published most expansively in his 700-page seminal work “The High Cost of Free Parking,” was that everything that most people think about parking was wrong.

Free street parking, Shoup wrote, makes parking and driving worse. The low cost creates a scarcity of spaces that leads people to spend time and fuel circling blocks in misery. And city planners’ efforts to solve this problem by mandating that homes and businesses provide more cheap parking only worsen the situation.

According to Shoup, this parking conundrum is foundational to many of the ills in modern urban life: congestion, sprawl, pollution and high housing costs.

Shoup presented his ideas with a cheerful countercultural undercurrent and sprinkle of quirky history.

In a 2014 interview with The Times, Shoup noted that the first parking ticket for an expired meter was given to a Protestant minister in 1935. The fine was dismissed, Shoup said, “on the then-novel explanation that the minister had gone to get change for the parking meter.”

Shoup’s message, persistence and style gained him legions of followers around the globe. The most ardent called themselves “Shoupistas.” The professor embraced the attention and happily accepted a playful moniker for himself, “Shoup Dogg.”

Michael Manville, chair of urban planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, said Shoup leaned into the spotlight because he realized it would help spread his ideas and because he just liked talking to people about parking.

“He spent so much time with his writing because he wanted to make it accessible,” said Manville, who first met Shoup as a UCLA graduate student in 2001. “He spent so much time with presentations because he wanted to make them entertaining. He built a method where he was always ready to explain to an activist group or a politician, ‘Hey, the missing part here is parking.’”

Shoup acknowledged that inveighing against free parking was not popular. He began a 2006 article in academic journal Transport Policy by nodding to parking conventional wisdom through a quotation from George Costanza, the obsessive sidekick from the 1990s sitcom “Seinfeld.”

Parking at a garage, Costanza said, was “like going to a prostitute.”

“Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I can get it for free?” Costanza said.

While Shoup mostly traveled by bicycle, he told The Times for a 2010 profile that, when he drove, he often circled the block searching for free parking.

“I don’t like paying for parking,” he said with a shrug. “But free parking is ultimately not beneficial.”

Shoup’s policy prescriptions attempted to take into account the public’s prevailing views. He believed that cities should charge market prices for street parking and that the resulting revenue should be directed to improvements in the surrounding community.

This blending of classical economic theories on supply and demand and understanding political realities helped build his practical influence, wrote Bill Fulton, a former student of Shoup’s and an expert on California planning issues, in a remembrance published this week.

“If you give that money back to the neighborhood where the paid parking is occurring, you can provide a tangible benefit to that neighborhood — and begin to overcome political opposition to paid parking,” Fulton wrote.

Shoup was born in 1938 in Long Beach. His father was a captain in the U.S. Navy and the Shoups were stationed in Honolulu when Pearl Harbor was bombed.

In 1968, Shoup earned a PhD in economics at Yale and, in six years, became a professor at UCLA. He remained there his entire career, retiring in 2015.

Fulton recalled that Shoup used to joke that he came upon parking as his life’s work because it was “the bottom of the barrel.” Most public policy academics studied more prestigious national and state issues leaving few interested in plumbing the depths of local policy. Among the few who explored local government, everyone ignored two issues: parking and sewage.

“Don didn’t want to study sewage,” Fulton wrote. “So he studied parking.”

As mayor of Ventura in 2010, Fulton brought Shoup’s ideas into reality through a parking strategy for the city’s downtown. The city began charging for some of its parking spaces, which spurred employees of local businesses to use nearby free city lots, freeing up curb spaces for customers.

By that point, numerous cities around the country were experimenting with Shoup’s ideas. The Parking Reform Network, a nonprofit founded to advance Shoup’s ideas, has documented policies in more than 3,000 cities that rely on Shoup’s research.

On the nonprofit’s website, over 70 people — including mourners from Bogotá, Colombia; Mexico City; Istanbul; Brisbane, Australia; and elsewhere — have shared memories of Shoup and celebrated his scholarship.

One of the biggest changes inspired by Shoup’s work came in 2022 when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation that eliminated mandatory parking requirements for most developments near mass transit across California. Newsom said the law would reduce the cost of housing while lowering climate change-inducing car trips.

“Housing solutions are also climate solutions,” Newsom said.

The law took effect when Shoup was 85 years old.

Shoup liked to acknowledge his later-in-life success, according to his wife, Pat Shoup. He published “The High Cost of Free Parking” when he was 67.

“He always said it was fine to be a late bloomer if you made it to the flower show,” Pat wrote in her husband’s death notice. “He made it and left a long trail of blossoms in his wake to benefit others.”

Shoup remained active following his retirement from UCLA. He continued to teach and was often seen within the Luskin School of Public Affairs building, per a remembrance published by the university.

Rep. Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) marveled at Shoup’s energy and how the professor continued to inspire people. Recently, she watched a crowd filled with people of all ages rapt as he gave a lecture on reforming handicap parking laws to increase access for people with disabilities.

Friedman, who authored the 2022 parking law when she served in the state Legislature, said the army of Shoup adherents provided a critical mass of support as she tried to move the bill forward.

“He inspired a passion among his students and fellow academics that turned his work into a movement,” Friedman said. “That’s what was unique about him.”

Shoup is survived by his wife Pat, brother Frank Shoup, his niece Allison Shoup, nephew Elliot Shoup, Elliot’s wife Megan and their three children.

There will be no funeral or church service, but UCLA will celebrate his life at a later date. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Donald and Pat Shoup Endowed Fellowship in Urban Planning at the UCLA Luskin School or the Parking Reform Network.