In the latest episode of The Envelope video podcast, “Nickel Boys” filmmaker RaMell Ross breaks down the film’s distinctive style and costume designer Arianne Phillips discusses dressing Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan in “A Complete Unknown.”

Kelvin Washington: Hello and welcome to another episode of The Envelope. I’m Kelvin Washington alongside Yvonne Villarreal, also Mark Olsen. Looking forward to what you all have to talk about today on this episode. Let’s start with you, Mark. Oscar nominations, maybe headlines, big takeaways for you.

Mark Olsen: Well, I think it was an exciting group of nominees. “Emilia Pérez” led the field with 13, followed by “Wicked” and “The Brutalist” both at 10. And then “Anora,” “A Complete Unknown,” “Conclave,” they’re very much in the mix with a lot of nominations. Now that we’re in the sort of postnominations phase of the awards season, it’s become a time for controversies, whether they’re ginned up by competing movies or not is in the eye of the beholder. But there’s been a lot of talk about the use of AI in “The Brutalist”; the lack of intimacy coordinators in “Anora”; there’s been a number of controversies springing up around “Emilia Pérez” involving the director, Jacques Audiard, and the lead actress, Karla Sofía Gascón; [and] the actress Fernanda Torres from “I’m Still Here.” There’s been all these controversies that have been coming up. And so it’s just kind of like that time of the season.

Washington: Par for the course, right? What about you?

Villarreal: Well, I’m excited for Mr. Conan O’Brien, who’s serving as host of this year’s ceremony. And I don’t know, 2025 has been a lot already, and I think we could all use some laughs. I’m just really excited at the possibility of seeing the string dance. Please tell me you know about the string dance.

Washington: I’m going to say yes.

Villarreal: What’s the string dance?

Washington: It’s the dance that Conan does.

Villarreal: Nice save. I’m really looking forward to it. I think if anyone can make us laugh, it’s Conan O’Brien.

Washington: Without a doubt. And you’re absolutely right. We could all use it. January didn’t start the way we wanted it to. Obviously, a lot happened around this country, around the world.

Mark, who did you have a chance to speak with this episode?

Olsen: I spoke to RaMell Ross. He’s an Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker, but he’s made his fiction feature debut with “Nickel Boys.” The film has been nominated for best picture and for adapted screenplay. It’s an adaptation of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead. It’s set in Florida in the early 1960s at a reform school. It follows two boys there as they’re just sort of struggling to survive in the really tough environment. And the film is told in this really innovative way with a kind of a point-of-view camera where you really feel like you’re assuming the position of these characters. And so it’s been just a really thrilling film to see make its way into the Oscar conversation. And RaMell just made for a great person to talk to. Looking forward to hearing that. Yvonne, what about you?

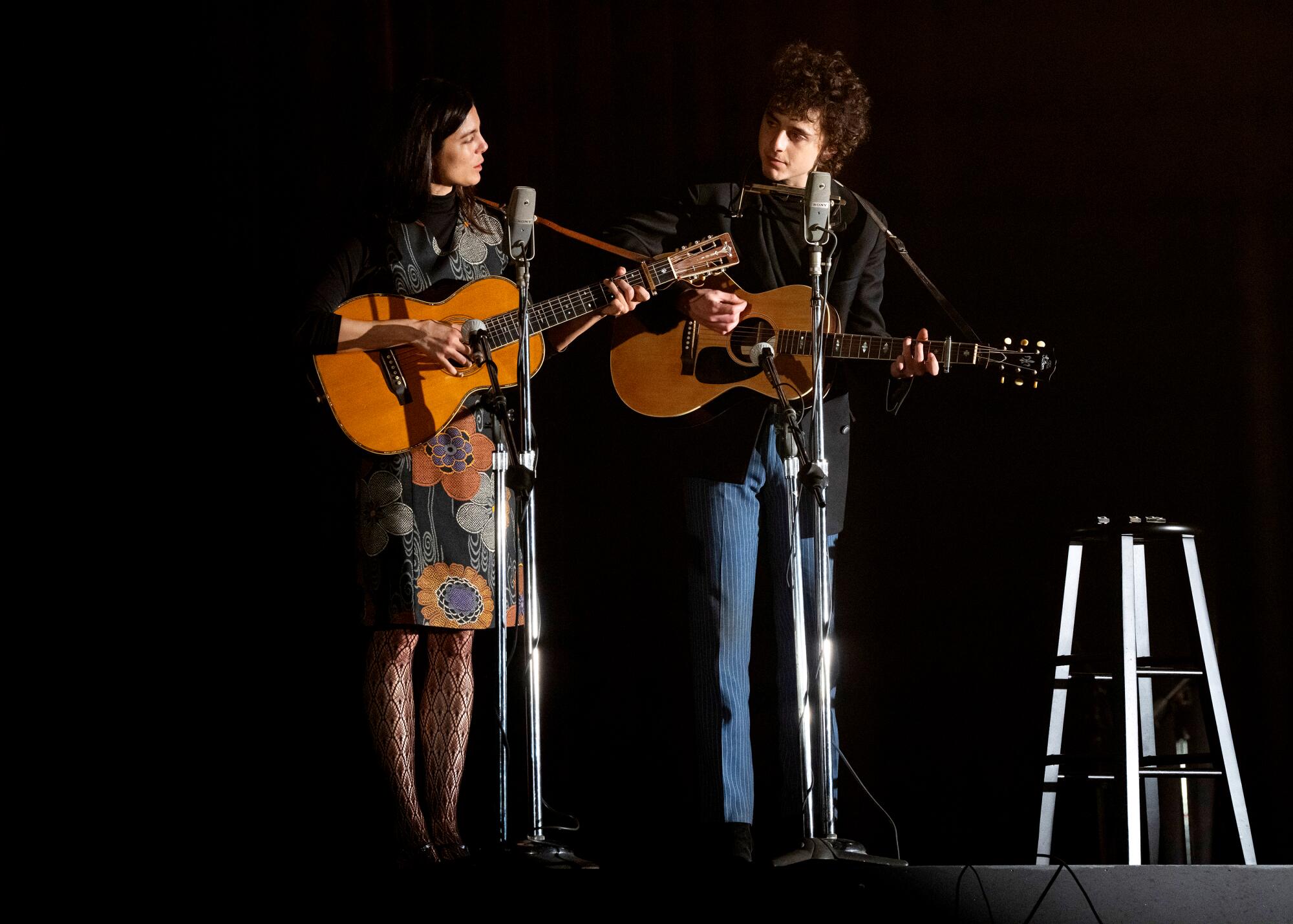

Villarreal: I spoke with Arianne Phillips, who’s the nominated costume designer from “A Complete Unknown,” which tracks the rise of Bob Dylan, played by Timothée Chalamet. You know, it’s a film that mostly takes place in the 1960s, and it feels like maybe that’s not a lot of time to work with. But she really captures the evolution of Bob’s style, whether it’s the early days of him and the sort of working-class look of Levi’s and stuff like that, to maybe his more iconic looks, which is like the leather jacket and the sunglasses. So it was interesting to talk to her. I mean, she’s worked on other things like “Don’t Worry Darling” or “Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.” She’s worked with Madonna, so she knows what it’s like to capture the essence of a musical star. So it was nice speaking with her.

Washington: I should have worn my leather. I missed that opportunity.

All right, without further ado, here’s the next episode.

Ethan Herisse, left, and Brandon Wilson in “Nickel Boys.”

(Orion Pictures)

Mark Olsen: Welcome back to The Envelope podcast. I’m Mark Olsen. And I’m here today with RaMell Ross, director and co-writer of “Nickel Boys.” One of the things that’s so remarkable about the movie is the way that the directing, writing, acting and cinematography of the film combine in this really unusual way. It feels almost like one gesture. Can you talk about what made you want to approach the film in that way?

RaMell Ross: I’ve never thought about it as one gesture. I like that language formation around the film. I think it stems from my documentary practice. I call myself a liberated documentarian to sort of not be beholden to the old ethical values that sort of didn’t really hone into the local myths and the local truths and kind of taking a scientific approach to photography and art. But, separately, I think it’s natural for me to have as many good ideas coming from all directions and to have the sort of hierarchies be fluid, because why not? And I know exactly what I want to do and I know how I want it to look. And so I’m not worried about the film itself swaying, but everyone that is collaborating on a project, they’re like genuinely brilliant people. And how nice is it to have as many brilliant voices in the room at a time.

Olsen: It is so interesting how similar “Nickel Boys” and your documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” are. They use some of the same techniques, they do have a similar feel in a way, and that just seems very unusual in making that switch from documentary to fiction.

Ross: I don’t draw really strong lines between the two because this film, similarly with the documentary, “Hale County This Morning, This Evening,” are just emerging from my art practice. And so the ideas that are in this film, you know, I’ve been working on them and developing them for a fairly long time. And so it’s just about finding collaborators and finding a space for a soup of ideas to manifest into something more palpable or palatable for others. I will say, though, that this project, specifically, because it emerges from a genuinely true story and one that has a specific tragedy about it, that makes you want to stay true to the source content. [Co-writer] Joslyn Barnes and I, we went to the source material, and we realized that the form of the film should emerge from it; it’s not something we should impose onto the project, but kind of how do these images want to be and what is the best way to elevate the Dozier School story to the annals of cinema.

Olsen: Can you tell me a little bit more about your art practice and how you sort of wanted to step forward from that into filmmaking?

Ross: My practice starts with photography, and I take it so seriously and have spent I think around 15 years now, living in a very specific community in Alabama photographing. And when you’re there, and you know people, and you’re trying to represent them and trying to present an experience of the community and the folks for other people, I think you encounter these ethical dilemmas about the limitations of photography and the limitations of film. And my process essentially emerges from trying to figure out strategies to deal with this really complex relationship between the reduction of photography and the cosmic beauty of the human experience.

Olsen: And what for you opens up by stepping forward into filmmaking?

Ross: One thing is the scale of resources. There’s not much money for art just for art’s sake, it seems. And I think the audience is a thing where — millions of people can come across the ideas if it’s in a film form, that is fiction specifically. Also the film medium itself is the most powerful if we don’t consider music, which quite often is not as directly linguistic or conceptual. It’s very emotional, obviously, but [with] film you can really incept someone’s mind. And I think if we don’t think of film as inception, then I think we’re really not thinking about what we’re doing.

Olsen: And so do you feel like you’re exploring the same essential ideas and themes in a fiction film, in a documentary and in your art practice? Like they really do sort of all coalesce for you?

Ross: My documentary, “Hale County This Morning, This Evening,” was about trying to kind of approximate a type of consciousness in film form and trying to expand the image of people of color by using a sort of strategic ambiguity and filming in the community with these specific folks for longer than anyone has ever filmed in order to be there for moments that only family members can witness, which is a sort of universal thing. My sculptures and my photography are interested in very similar ideas, which is bringing people to a place and giving them these expansive but also myopic experiences. And “The Nickel Boys” comes around and Colson’s narrative is so familiar and so powerfully rendered, my co-writer and I realized that we can distill it and we can populate it with the poetry that’s kind of missing from that time period. And, with that, then taking the camera into the body and making it point of view, we’re participating in the same type of knowledge production and expansiveness of the image of specifically people of color and Black subjectivity, but inside a narrative. So it allows you to sort of fall back into understanding and then slip back into poetry. So you’re not just, you know, in this unmoored meaning-making space.

Olsen: I’ve heard you say that in writing the adaptation of “Nickel Boys,” you felt like one of the best ways to pay tribute to the book was to try to get away from the book.

Ross: Strange, right?

Olsen: Can you explain that?

Ross: It’s too good. And I think the more powerful the book, the more concise, the more economical the book, the more its mythology is rendered in every sentence, the more difficult it is to adapt it to cinema, because you can’t do everything. And if you take things out, you’re losing the power of the gestalt, essentially, of the larger gesture that they made. And so, yeah, Joslyn Barnes and I tried to figure out how to, like, just get to the spirit or the essence and then sort of leave the book alone and say Colson did his thing. And we actually don’t want to do that, because we actually can’t. And we’ll do a companion piece. And isn’t that a relief?

Olsen: And then were you in touch with Colson as you were working on the script? Did you get any kind of feedback, or did you talk to him at all about this approach you were taking?

Ross: I didn’t. When I [was] asked before, I always remember writing like a really long email and then getting like one or two words back, like, “Good luck, champ” or something like that. But then I went back the other day and looked at it, and he actually said, “I loved ‘Hale County This Morning, This Evening.’ I’m not going to read the script” — because I think I sent him the script right when we had finished and we were approved to make the film — “I look forward to watching the movie. Best of luck.” But he didn’t want any part in the script-writing process, nor in the movie process. But it’s similar to what he did with Barry [Jenkins] and “Underground Railroad.” It’s just his, I think, relationship to his IP.

Olsen: Has he given you any kind of feedback on the film itself? Has he watched the movie?

Ross: He did tweet, “Go watch the ‘Nickel Boys’ movie.” No feedback, but that to me is a gesture of [respect].

Olsen: But do you want to know?

Ross: I think I’m curious, but at this point in time, given how recently we’ve released it and how chaotic this process has been, I’m not thinking about it at all. I imagine that I’ll be in conversation with him at some point, or we’ll grab a drink, and I’d be really interested to hear specific parts that he enjoyed or specific parts he didn’t. And if he could break it down into those ways. But I mean, at this point in time, I’m much more interested in getting rest.

Olsen: And the one thing I just want to clear up for myself is, I’ve seen in some other interviews as you try to explain the way that you shot the movie, you kind of don’t like the term “point of view” and you prefer this term “sentient perspective.” Can you just explain to me a little bit what that distinction is and what sentient perspective is to you?

Ross: Point of view is, I think, the origin of that camera use. And I think it makes more sense when you’re talking about GoPro footage and action footage and some of those early films like “Lady in the Lake,” or even porn or these ways of just being in a wide frame of view and trying to approximate what it means to be from a single-point perspective but without specificity as to where the person should look and control over the gaze. But I think that’s just the entryway into the idea of trying to make the camera an organ and trying to really attach it to a person’s consciousness to align it with the person who’s watching. And so sentient perspective is something that Jomo Fray, the wonderful DP on the film, and I came up with just as a way to not let the language somehow undermine the way in which we wanted to approach it. Because if you talk about things the same way, then you’re probably going to be towing in some of those values unknowingly. Which is why new language comes in. So since sentient perspective is just way more, I think it just touches the spiritual intent of the project and having the camera do more what vision feels like, not what vision is. And with that, there’s a touch, and there’s a grace, and there’s like a true purpose to it aside from just aligning the viewer’s point of view with the body that the camera is on.

Olsen: What was it like for you moving from writing the script to actually sort of prepping to shoot and working with Jomo, your cinematographer? I’m just curious how you figured out where the camera needed to be and what the viewer needed to see.

Ross: I don’t think that this film would have made it this far if we weren’t deeply meticulous even before we got to the pre-preparation stage. Joslyn and I wrote the treatment with camera movement, which we wrote before the script in order to have a conversation and to write the film about where the characters are looking and the meaning that is being made from where they’re looking and how they’re looking. And so camera location and camera movement was really kind of premeditated. I think the breakthroughs that come when working with someone like Jomo is figuring out how that feels, because there’s a difference between knowing where the camera should go and where to look and how it should feel when the camera’s moving, or how the camera should deal with depth of field in relationship to the range of equipment that we can have and how to produce a scene.

As a documentarian, it’s quite easy to photograph in film because you have a camera, you go into a space and you deal with what’s already there. It’s very similar to, like I love Jon Stewart when he talks about how people are funny. He’s like, being funny is easy. The world gives you the momentum and the context for funny. People can be funny in real life. But to go onstage and to be funny when you have to build it yourself is a completely different thing. And that’s like the fiction film process. You need someone like Jomo and Nora Mendis, who’s the production designer, to build the space so that it feels as real and as palpable and as visceral as our real lives. And then you can go in with the things that you already know how to do really well. And so a lot of it was about touch with Jomo and the shot-listing and actually dealing with the spaces itself. Because what Joslyn and I wrote in terms of location, it’s not the location we find or get because it never really works that way. And so you have to adjust to, “Oh, we’re actually not going to be able to look to the right. We’re going to have to look to the left most of the time, and we can’t go up as far as we want. So how do we want to make those adjustments?” But Jomo and I spent many, many hours with my little DSLR [camera] in his Airbnb reviewing all the camera movements and practicing the hug and making sure that when we went on to set, we at least had a heads-up so that we could make adjustments that were additive and not just trying to accomplish the thing.

Olsen: Were you having to build camera rigs? Were you having to make your own equipment to accomplish what you were trying to do?

Ross: Yes. And that’s the wild part. I would have shot the whole thing handheld if we had to, because the camera needs to be in certain places. But how do you have, as Jomo would say, as little amount of artifice as possible? And with [handheld], there’s so much artifice behind the camera. The rigging that him and his rigging crew did and the inventive methods they did to get us so close to the body with a 6K camera — this is a Sony Venice, Rialto mode, like some of the same cameras they used on “Top Gun” that they’re putting in those jets, Imax quality — to get that to be able to move relatively close to the human head and to be able to be in proximity to the body so that it’s at least conceptually convincing that it is one’s eyes, is a feat in itself.

Olsen: And then what was it like in explaining this to your actors, to Ethan Herisse and Brandon Wilson because, you can tell me I’m misunderstanding this, but there are scenes in which they’re in that scene, but they’re physically maybe not present on set in that moment, where Jomo was operating the camera, you sometimes are operating the camera. What was it like for the actors to have to adapt to the process of making the movie in this way?

Ross: I think Aunjanue [Ellis-Taylor] had it the hardest because she didn’t have a scene partner in any traditional sense. Like at least Brandon and Ethan had each other most of the time. Most of the time that they have scenes, they’re with each other, and they could hang out, and one was always behind the camera. But Aunjanue was kind of an island to herself. I think one benefit of the process was that I underestimated how difficult it would be for them, and maybe, in fact, I didn’t even think about how difficult it would be for them. And so they never asked about how we were going to shoot it. They knew it was POV, but they concentrated on their lines and and doing their character thing. And so on Day 1, I’m like, “All right, guys, look here.” And they’re like, “What do you mean?” And then we go about making the film. So I think trial by dropping them into the water and asking them to swim — they can all swim, so they just had to kind of unload a bit of the previous modes that they’ve learned to get through this stuff.

Olsen: Because it strikes me [that] there’s something so selfless about it on their part, because they so often are less in the scenes that their characters are more in. I find that so striking.

Ross: It’s a strange thing. The writing process for that is also interesting because if you read the script when they’re speaking, if they’re the character, it always says “OS,” it always says “offscreen.” And so we knew that we’d have to, at least in the sound design as well, figure out a way to give their character — who is not being seen, who is the camera, who is the camera operator, who is also the audience — a voice that felt tactile, that felt embodied but also through the screen. And so it was a strange process. But I must say, for almost every one of those scenes, each one of them was behind the camera and they were delivering their lines. It’s just that the person in front of the camera, the actor in front of the camera, could not look at them or really take that person that’s beside the camera operator as the person. And many times, of course, we’d have to cut because someone would accidentally look at the actual character and not the camera because that’s most natural. Yeah, it was a fun process.

Olsen: And then there’s a scene in the cafeteria at the school that we see twice, from each of their perspectives. Can you talk a little bit about why you wanted to do that and what it meant to you to have that one scene run through from two perspectives?

Ross: It was scripted that in that moment in the cafeteria, we would jump to Turner’s point of view, but it wasn’t scripted that we would run the same scene twice. That’s something that was developed over the editing process. Joslyn and I knew that we wanted to run one scene twice from each perspective at some point in the film. And we knew the gesture had power. But we didn’t know where and how that power would be revealed, even to us. And we were having a bunch of trouble with that scene, because some could argue it’s one of the most important, if not the most important, like the first time you see Elwood. At some point in time, Nick just ran it twice from each perspective. Nick Monsour is our editor. And it was a game changer for the film because it sort of instantiated something that we’d always talked about but we’d never materially articulated in the edit, which is that at all points in time there are two perspectives going on, and they’re having two completely different experiences of the moment. And this was important in the writing process. They have different timelines that are going on conceptually while they’re in each moment that sometimes plays out over their visuals, which is very subtle. But that instantiated it and offered the audience a gesture that I think gave them a curiosity to the point of view that I guess you can’t predict until sometimes you get into those editing moments.

Olsen: I think what’s so remarkable in that moment is, for me at least, it opened the movie up in a way where instead of feeling like I’m locked in with this one character, you felt like it could bounce around. It did open up what the perspectives were going to be like. To me, it’s just like suddenly the movie just unfolded in a way that I found really compelling.

Ross: That definitely was by intent. But the power of the moment is the hardest part. How do you get to it working? Because you saying that you felt that is not the gesture. It’s the power of the alchemy of the moment and what comes before and maybe what’s after too.

Olsen: You mentioned Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, and there is something in her performance, she seems particularly adept at this style. She seems very comfortable with the direct address.

Ross: Which is strange because she wasn’t. Even during the Q&As, she talks about how difficult it was, and when she’s talking about it, you can see on her face her recounting it and that emotion coming back up. And she was like, “Man, it was wildly difficult.” But she did say that it was a challenge that she’s always wanted. Not that specific moment — she’s wanted to be asked to do things that she’s not typically asked when she’s acting that force her to be, I guess, in a type of present.

Olsen: And what was that like for you as a director on set? I mean, you don’t have a lot of experience working with actors. Aunjanue, obviously, is someone with a lot of experience. She really knows her craft, knows what she’s doing. What was it like for you to maybe feel her discomfort or how did you work with her in those moments?

Ross: I think I only have coaching metaphors or sports metaphors because I played sports for so long. But like, when you said that, it made me think of, if you’re coaching someone and they’re the best on your team and they’re amazing, and all of a sudden you play a team that has a formidable opponent, what’s your job at that point? It’s just to reassure your guy, or your person, that they’ve done all the work, they have the skills, they’re being presented with someone who’s as fast as them or as dexterous as them. To quote Denzel [Washington] in “Fences,” take the crookeds with the straights. I think it was just about helping Aunjanue not feel insecure about the way that she was assessing the situation. Because in this first moment, in the same way that when someone does something new for the first time, their assessment of the quality of it is mostly off. How do they have a comparison? So we know that Aunjanue is doing amazing, but she doesn’t know she’s doing amazing. Everything that she did was was deeply powerful and meaningful. And as a director, it’s mainly about making sure that it aligns with where the character is in their arc relative to that scene. But she already had it.

Olsen: Tell me a little bit more about the hug. It’s so tactile. It’s something I don’t know I’ve ever seen or felt watching a movie before. You’ve mentioned how you had to rehearse and figure out how to do it. That simple idea of like, “the two characters hug,” was that really difficult to figure out how to make that work?

Ross: It was and it wasn’t. In the writing process, Joslyn and I were like, “We want a hug to happen here.” And you write it in, and they’re going to hug, and it’s going to work or it’s going to not. And there’s no other option. And with Jomo and having the DSLR and practicing it, it was about having the least offensive hug. Because you’re not hugging, you are moving the camera forward. How much are you asking the audience to suspend disbelief? And so we would practice like where the rack focus would go, how much of the shoulder would be inside the frame, the kind of speed of approach and the speed of release, just to get to something where we thought the audience could not genuinely be offended. Because I think Jomo’s best example of the quote-unquote failure of POV, typically, to have an emotional connection and to approach something that’s reasonable, is in “Lady in the Lake,” the main character, who’s the camera, gets a kiss from a woman and she kisses the lens and so she’s kissing the eye. It doesn’t make any sense. And there’s no human being that watches that and is like, “Oh, I got a kiss.” It’s like, “That’s weird.”

Olsen: There’s a whole other element to the story where we’re meeting one of the boys as an adult having survived the reform school. We come to understand what it means to carry trauma forward in your life. Can you talk a little bit about that adult portion of the story? What did that part of the film mean for you?

Ross: This is the Chickie Pete moment in the bar, essentially. Man, what an amazing scene. That guy’s name is Craig Tate. He blew everybody away. The film is very impressionistic and very expressionistic, and it’s kind of more interested in the sort of oneiric aspects of life, the more daydreaming, visual use of the camera as it relates to realism, as opposed to the sort of gritty, hard, “The Wire” type of footage or approach to reality. And I think in that moment, with our camera language, we wanted to get to something gritty and something really real and something that felt truly inhabited and human. And I think everyone knows a person who is like Craig Tate in that moment, who is like Chickie Pete, who is so much a victim of their circumstances that it plays itself out in almost every readable way. And it’s hard to not read into everything they do as a product of whatever’s happened to them. And I think it’s just the most devastating part of the film to watch because it just feels so spot-on. What Craig Tate did was spot-on.

Olsen: And was it hard to cast that role? Because I have to say, to me, that’s the kind of supporting performance that I just love, when somebody comes in, does one scene, just blows the doors off and then they’re gone.

Ross: It was. I’ll say that it was near impossible to find Craig. When you’re casting, you’re genuinely, or generally, at the whim of your casting directors. And so Megan Lewis was local in New Orleans and Vickie Thomas was our national casting director. She brought Craig Tate. And we asked very specifically, because there were two main fellas for that role ,and we were like, “Which one would you choose?” And she was like, “I’d go with Craig.” And we went with Craig.

Olsen: Especially coming from a fine art world where only you are the person working on the project, what has it been like for you, first on a documentary, now in a fiction film, to realize that you have to trust in other people, your local casting director. I don’t know how you are as a delegator or what it’s like for you personally, but is it difficult to sort of learn how to let people like that do their job?

Ross: Yes and no. It’s quite easy, because I don’t want to do it, like I wouldn’t want to cast. I think maybe my personality in some ways fits the role that I have in the film as a director. I see myself more as an image maker than anything. I actually don’t like telling people what to do, nor do I like choosing people over other people. And so, when we were doing Ethan and Brandon, when we’re choosing the main roles, Elwood and Turner, and I’m like looking at the casting thing, I’m just like, “All you boys would be so good. Like maybe for not this movie, but, like, your life is going to change. I don’t want to say no.” And so it’s actually quite hard for me personally, because I get emotionally invested in every aspect. It’s nice to have people who are experts to be able to narrow the field and then present a nondizzying amount of information to be integrated into the project.

Olsen: When we meet one of the characters later, he’s trying to understand what’s happened to him, what was done to him, as he’s researching into the school, learning more about the history of the school. That part about the story from the book, and just the real history of what happened at that school, what did that mean for you as far as how it connected to the story?

Ross: I think it takes on a sort of hypothetical or a speculative element in my life, because I don’t have a relationship to that type of trauma. But it’s a beautiful thought experiment to take oneself through what it would be like and to try to empathize, and in this case, to live vicariously through someone who has experienced that, especially through Colson’s narrative. And I think it was really meaningful to develop an adult character that is invested in self-exploration in a way that could not only restore his own sense of self, which he hadn’t even realized he had lost, but then also do justice to a historical injustice and also kind of embody the values of the person who changed his life the most. It’s kind of like you just have an ideal scenario for self-revelation as it relates to societal injustice or something. So it’s meaningful to imagine in these ways.

Olsen: What has it meant to you to have the movie coming out in the moment that it is, when so much of what’s been reduced down to this concept of “DEI”? The very notion of how we teach history, what kind of history we’re going to talk about or not talk about, has become so charged and controversial. And this movie does in its way, address a lot of that.

Ross: Man, I just have to say, it’s so weird. And I think I maybe saw this on the internet yesterday. It’s, like, a room full of white guys is merit, but any time that there’s a woman or a person of color in the room, it’s DEI. It’s so baffingly stupid. But, hey, we’re here. I can’t help but smirk. I think maybe humor is a defense or a coping mechanism that comes more easily to me than others. But the idea that over 111 years, the Dozier School for Boys literally murdered people and tried to bury that history. And in 2024, that history not only has been unearthed but it’s been elevated to the annals of cinema and cinema history. And now it will never be forgotten. It’s kind of incredible. And I’m happy to be the person to usher it, with all my collaborators and producers. But I think it means more than the world. I wish people took that as a sign that whatever they do will become known, and so to maybe be a little bit more longitudinally considerate of how people relate to their legacy.

Olsen: Considering the film is so unconventional, what has it been like for you just sort of seeing it through its release, being a part of the marketing, the release of the movie? What has that aspect of just getting the movie out into the world been like for you?

Ross: It’s been one of, like, constant learning, because I’m just most interested in ways of communicating, ways of translating or placing ideas into form. And I just get to learn how people engage with their world, the world that we made, art itself. And there’s been nothing more interesting than the conversations with people who have watched it, having conversations with interviewers who are interested in all the elements of the film and its release. It’s been a rewarding discourse that I think is kind of just starting.

Timothée Chalamet and Monica Barbaro in “A Complete Unknown.”

(Macall Polay / Searchlight Pictures)

Villarreal: Congratulations are in order. With “A Complete Unknown,” this marks your fourth Oscar nomination, right?

Phillips: I still can’t even fathom it. My 8-year-old self is still in shock.

Villarreal: It almost feels full circle in a way, because your first nomination was for 2005’s “Walk the Line,” which also had you collaborating with [director] James Mangold. That was also a musical biopic. What do you remember about that time of your life, both professionally and personally, when that project came your way?

Phillips: It was thrilling. I had been working on a movie called “Identity” with Jim Mangold. At the time, Johnny Cash was alive and he was working with him on the script [for “Walk the Line”], and I was so excited. I actually was a Johnny Cash fan as a teenager. I wasn’t raised around his music, but he was kind of a punk-rock folk hero. And I was really into his music. And so that was exciting. So I got a little head start on that, just immersing myself in that world. And that movie was really seminal for me in so many ways, being able to tell a story about a musician. I started in music videos, which was my dream when I was a teenager. And I have found, looking back 20 years, that I’ve chosen a lot of films that have had music in the center point. I really love music and film because it adds a levity and an emotional layer that not only lifts the audience in the story but the crew when we’re making the film. Also, I met my partner and my husband during “Walk the Line,” so it will always remain special for me in more ways than one.

Villarreal: Did you have expectations of what having an Oscar nom would mean [for your career]? And did it meet those expectations?

Phillips: I think it was just like a wish fulfillment of an 8-year-old. It wasn’t anything that I thought that I was going to ever experience. I have to say I’m an awards-show junkie. So I think the first awards show I remember seeing was when “Oliver!” won best picture. And that dates me. I think I was 5 or 6 years old. It’s wonderful to be a member of the academy, and it’s one of our most hallowed institutions. It’s thrilling to be part of the community in that way.

Villarreal: This reunites you with Mangold for, what, the fifth time now?

Phillips: This is our sixth film.

Villarreal: So, when he tells you, “Hey, I’m doing this project on Bob Dylan,” what are those initial conversations like?

Phillips: Well, Jim called me up. Our schedules haven’t meshed for a while. So he called me up way in advance in 2019 and said, “Hey, I think I’m going to make this film about Bob Dylan. I’m not ready to share the script with you, but you should read the book ‘Dylan Goes Electric!’ by Elijah Wald — that what the script will be inspired by.” And I did immediately. I was raised with Bob Dylan’s music. He’s my parents’ generation. And I’ve found out since [that] I have so many parallels: I was born in New York City in the West Village at the time when Bob Dylan was living in the West Village. And just a lot of, for me, personal, similar experiences as a young person moving to New York, looking to find my way. So learning about his early story of how he came to New York was really exciting, because I only really knew Bob Dylan through the icon, the Nobel Prize winner. I was a fan as a kid. My parents had the records. And as an adult, I’ve seen him play many times live. So having that layer of connection, both nostalgic from my childhood and then also as an adult, it was the most exciting research to dive into to learn more.

Villarreal: What era [of his] did you watch Bob Dylan perform? What was that like?

Phillips: I saw him in the ’90s in New York and the late ’80s, kind of like the Traveling Wilburys era. The records that really influenced me were the two records my parents had. My dad is a jazz musician, and we mostly had jazz and opera and classical, but we did have “Nashville Skyline” and “Blonde on Blonde.” Those two records remain two of my favorite records. They are in me. They’re kind of in my DNA as a little kid dancing in my pajamas on like a Sunday morning to Bob Dylan.

Villarreal: I used to, in college, track my drive from home to school by listening to “Like a Rolling Stone” [on a loop] — see how many I could get through. It would sometimes be like six or seven times.

Walk me through the research process for you. I know when I take on a story, my favorite part is the research. And I know Bob took a look at the script, but that was, like, maybe the extent of his involvement. What’s the balance for you — how much are you looking at archival footage to really help you in this process and how much are you wishing for the personal archives? What is crucial for you to get your job done?

Phillips: I would say research is always my favorite process. It’s quiet time. It’s alone time. It’s when I become inspired. It’s where I start the layering process of design in my head, and also tone and mood. And in this case, I had an unusually long research period, an unofficial period, because Jim asked me to design this maybe in 2019 to shoot in summer of 2020, and [then] COVID happened. And then when we came out of COVID, we had many scheduling delays with availabilities with Jim and Timothée. So it took us a minute. We finally got going in 2023. It was four years I had since I read the book. So while I wasn’t on salary, especially during COVID, it was a wonderful, purposeful project for me. So during COVID, I got a real head start in starting to read a lot of books about characters in the film, whether it was Joan Baez or Alan Lomax or Pete Seeger or Suze Rotolo [in the movie, the name of Dylan’s muse, played by Elle Fanning, is changed to Sylvie Russo] — just learning about Bob through the people in his life, which is really in sync with how our story unfolds. Jim had quite a few conversations with Bob, and I think they happened mostly during COVID. So knowing that he was engaged in the script really gave gravitas to the whole experience, much like “Walk the Line,” knowing that Johnny Cash was giving [Mangold] his notes.

It was just creating a timeline first, excavating and forensically looking at the script on what we were re-creating on known events, and then in between [that] is the private story. Bob Dylan was very well photographed; [there was] a lot of news conferences and newsreels in the early part of his career. Now, he’s more press-shy. So, we’re lucky in that we had a lot of access to footage and photos. And, of course, I read a lot of books which really filled in a lot of blanks. But we didn’t have personal photos. We were able to find a couple via his archive or randomly other people who took photos of him. Having that is always a challenge. Same with “Walk the Line” — we didn’t have access to Johnny Cash’s personal photos. So really it’s about, for me, creating a fluency and an understanding on Bob’s aesthetic and learning, from just being immersed in the research, what is the through line. I think if you look at your own photos or family pictures and films from our own lives, we can see there are certain things that we carry on aesthetically that we lean into. With Bob, which really helped me in terms of his silhouette was his boots. He always wore boots. He wasn’t wearing tennis shoes or loafers.

Villarreal: He was doing the boot-cut before people were doing the boot-cut, right?

Phillips: I found out some amazing gems, especially from reading Suze Rotolo’s book, “A Freewheelin’ Time,” where she spoke in detail about how Bob, when he first arrived in New York, spent hours in the mirror cultivating that very proletariat workwear look, which was really surprising to me because I just thought he was a more haphazard 20-year-old. And then she also spoke about [how] his jeans never fit quite right over his boots. He wore cowboy boots around ’63, these rough-out boots. So she made a little denim insert in the inside of his jeans, which I spoke to the Levi’s people quite early on too, so they could vet the denim he’s wearing because he also consistently wore denim. And they were saying that basically that little denim insert that Suze Rotolo put into Bob’s jeans was kind of the first boot-cut jean, in a way, and it would definitely be the precursor to the flare, the Summer of Love, down the line in the ’60s.

And his hair — I worked with the brilliant hair designer Jaime Lee McIntosh, and we worked together with Jim on these three different points in our story: when we meet [Bob]; when he starts to get known in the West Village, in the coffeehouse scene. So, we meet him in like ’61, ’62 and then ’63, ’64 and then, of course, ’65, when he’s adopted this very mod look, having been to England. And you see his style has really evolved. And it’s so interesting, from a 19-year-old to a 24-year-old, not only how much incredible music he wrote, enduring music that is some of our most important music of the 20th century, but he also evolved so much in terms of his style, which would mirror kind of the evolution of this young artist.

Villarreal: Typically with musical biopics, or often with musical biopics, it’s sometimes a cradle-to-grave story. Here, like you said, it covers ’61 to ’65, such a short time frame. And yet, as you discussed, there’s so much evolution that happens for him and his style. But when you hear that you’re covering a short span of time, are you like, “This is going to be so challenging?”Or is this like a perfect sort of window or time frame to dive into?

Phillips: For me, telling this story from ’61 to ’65, four years of his life, for costumes was a huge opportunity and really exciting because I could help move this story along visually. Usually, we’re working with the production designer just in terms of how technology changes over time or automobiles change over time or even architecture, depending how long the story is. So with just four years, I knew that the onus would really be on this evolution visually that would mirror the evolution of his music. Those first recordings are all traditional music. He’s dressing himself like his hero, Woody Guthrie, the working man, the proletariat, which is very indicative, I think, of any 19-year-old who’s really left home and trying to figure out their way in the world — and, in this case, it’s musically and visually. And we see him evolve as he’s playing in the coffeehouse scene and gaining notoriety and becoming more the artist he wants to be. And then eventually we really see it in ’65 where he clearly doesn’t want to be limited [as] a guy with a guitar, solo; he’s putting a band together, his music is evolving and so is the way that he dresses himself. He’s influenced by his travels to London. He adopts this mod look. He’s very influenced by the Beatles. [There’s a] confidence that he gains, [a] point of view, [from] not adapting to the expectations of saving the folk world and just being on his own trajectory of an artist wanting to play music, and now he’s 24 and wants to be in a band.

It was really wonderful to be able to parallel the work that Timmy is doing and the music is doing as it’s evolving in our story, visually, to express that, along with Jaime Lee McIntosh with the hair. When I think of Bob Dylan, I think of him onstage, the hair light — that beautiful halo — and being in his silhouette. It was really a thrilling opportunity to be able to be part of helping move the story along visually for the audience. The thing that I love about my job so much is that a costume can work as an assist to an actor to help them kind of get there, to be a “beam me up” suit to help feel what it’s like to embody the character. Having that evolution of Bob in our story from even just thinking about the shoes he wears, from the kind of work boots to the cowboy boot to the Chelsea boot, really tells a story, and also a story of personal confidence. When we leave him off, he’s the rock ’n’ roll archetype, the Bob Dylan that that we know. So that was thrilling to be able to be part of that process.

Villarreal: Tell me about working closely with Timothée. I know he’s talked about that he had to gain like 20 pounds. What did that mean for you in your job, checking in with him or fitting him?

Phillips: I think one of the great things about this movie overall is it’s not just Bob. We had so many costumes on everyone. We had 120 speaking parts. We had almost 5,000 background [actors], a third of which we dressed twice for different concert scenes. So we had a lot to track. My department, an amazing costume team in New York, we had a lot to track along with Bob’s evolution. It was an embarrassment of riches to work with such actors: Timmy, of course, Elle Fanning, who is my personal muse, Monica Barbaro, Ed Norton — it’s actually a reunion for Ed and I because we did “The People vs. [Larry] Flynt” together at the very beginning of both of our careers — Boyd Holbrook, Norbert Leo Butz, just many great actors.

Timmy was incredibly generous with his time. He had 67 costume changes, so we had to do a lot of fittings. And it’s not 67 costume changes set in one year. It’s set over time. So we had to fit it in chunks. And it was really great. It was kind of like summer camp in a way. We started our fittings in the beginning of June 2023 in L.A., when Timmy was either coming from or going to music rehearsal. So it was really great to live in that feeling of like, “We’re all working on this incredible project, and we play music in the fitting room.”

Villarreal: Was he singing in the fitting room?

Phillips: He was singing. It took me aback the first time I heard him sing because it was so moving. He’s committed, and he’s really focused, and he really does the work. That’s the best quality that you can hope for in an actor, especially when you have so much to achieve.

Villarreal: Did he ever pull you aside either during or at the end [of shooting] and say, “Hey, can I take this home? I really like this outfit. It really fits my vibe.” Was he like, “I need this”?

Phillips: No. The producers generously gave him a couple of things at the end of the movie, which I’m always thrilled when the actor gets to take costumes home, because that’s like the ultimate memento. I actually do this thing on every movie that [I’ve done] for the last few movies is that I’ll take the remnants of fabric, because we built most of Timmy’s costumes, and I make pillows. So I made him a black leather orange shirt pillow. I think I made him a polka-dot shirt pillow with a denim side. I do that as a little memento.

Villarreal: Were there looks that you were particularly excited to see come to life onscreen or ones that you were like, “If the audience only knew how much work it went into doing this look” — either for the Bob character or any of the characters?

Phillips: The polka-dot shirt has a life of its own. And for a film where the costumes are fairly quiet, that shirt, people remember it. When I saw it in the research, I just couldn’t believe it. I saw him wear that shirt in photos at Newport [Folk Festival] in the sound check, not at the performance. And we didn’t have the sound check in our script. I remember showing Jim the photos. One of the beautiful things about working with him over time is there is a shorthand there and and Jim wasn’t so sure about that polka-dot shirt because it’s so loud. And the thing that I love about working in Jim’s movies is kind of underscoring an emotional tone of the scene and not eclipsing what the actors are doing or being sensitive to those moments. So, Jim wasn’t sure. And we made the shirt because I knew that Al Kooper would be wearing it at Newport at the concert at night. So we made the shirt. Timmy loved the shirt and so did I. And at first, we didn’t know what color it was. But then I found a colorized obscure album cover of Bob in the shirt, and it was green polka dot, which even made it, I think, less attractive to Jim. Like, “Oh, OK, polka dots and they’re green.” But one of the things that I love about that shirt is that really shows us — like, Bob in 1966 goes completely wild with the way he dresses. He goes very mod. He’s wearing polka-dot suits, striped suits. So I thought it was really important that we see — and it existed — [that] we have hints of this aesthetic that would carry on beyond our film.

Villarreal: You have this experience in the rock ’n’ roll sort of sphere and also in costume design, which are sometimes at odds. How have you come to understand how to dress celebrity clients as characters in real-life narratives, and how does that sort of align, or maybe work differently, when you’re thinking about film characters as real-life people, real-life stars?

Phillips: I don’t dress people for the red carpet. My work with musicians — I started with Lenny Kravitz, worked with Courtney Love and Hole, and I worked with Madonna for 20 years. And the thing I would say about Madonna is that I was also, in tandem, working as a costume designer in film in between. So my first film was in the early ’90s. I met Madonna in ’97. I had already designed a few films. The great thing about Madonna is that Madonna understands: She takes on these characters and personas, and she’s famous for it and brilliant at it. And so with her, I had so many different opportunities, whether it was the cowboy persona of “Music” or referencing traditional Japanese dress. And part of the wonderful dialogue with her is she would read a book — like, she read “Memoirs of a Geisha” and then she wanted to become that character, [Hatsumomo]. It’s her ability to communicate in her music and also create characters. And then eventually I worked with her as a director for “W.E.” [She has a] deep understanding of how costume helps move a narrative along. And when working in music videos, you have performance music videos and narrative music videos. And [in] narrative music videos, you’re creating characters because you’re telling a story to music. It is intrinsic. That’s probably why I stayed with Madonna so long because she’s so prolific and works across genres that I got the opportunity to hone my skill as a costume designer and have all these incredible experiences with her, whether it was music videos or tours. I designed six of her tours and designed a lot of costumes. And working with her as a director is unparalleled.

Villarreal: And if that Madonna biopic ever gets off the ground, you have to be behind that.

Phillips: I am. Yeah, we’re just waiting for it.

Villarreal: We’ll have you back to talk about that. Before I let you go, we often hear from actors that they are not into watching themselves on film. So my final question to you is, do you watch your work?

Phillips: Yeah, I do watch my work. My husband has a tendency, any time a movie is on that I’ve worked on, he’s always watching it. So I definitely see it. I’ve seen “A Complete Unknown” more than I’ve seen any other film, because every time I see it, I’m emotionally moved. I love the film in a very deep way. I don’t know if I’ll ever look at this interview. I don’t particularly like looking at myself on camera, but I do love the work, especially because it is a time capsule for me creatively and the collaboration of the people I got to work with — my crew members, the directors, the actors and hold good memories.