SEATTLE — A second federal judge in two days has blocked President Trump’s effort to end birthright citizenship for the children of parents who are in the U.S. illegally, decrying what he described as the administration’s attempt to ignore the Constitution for political gain.

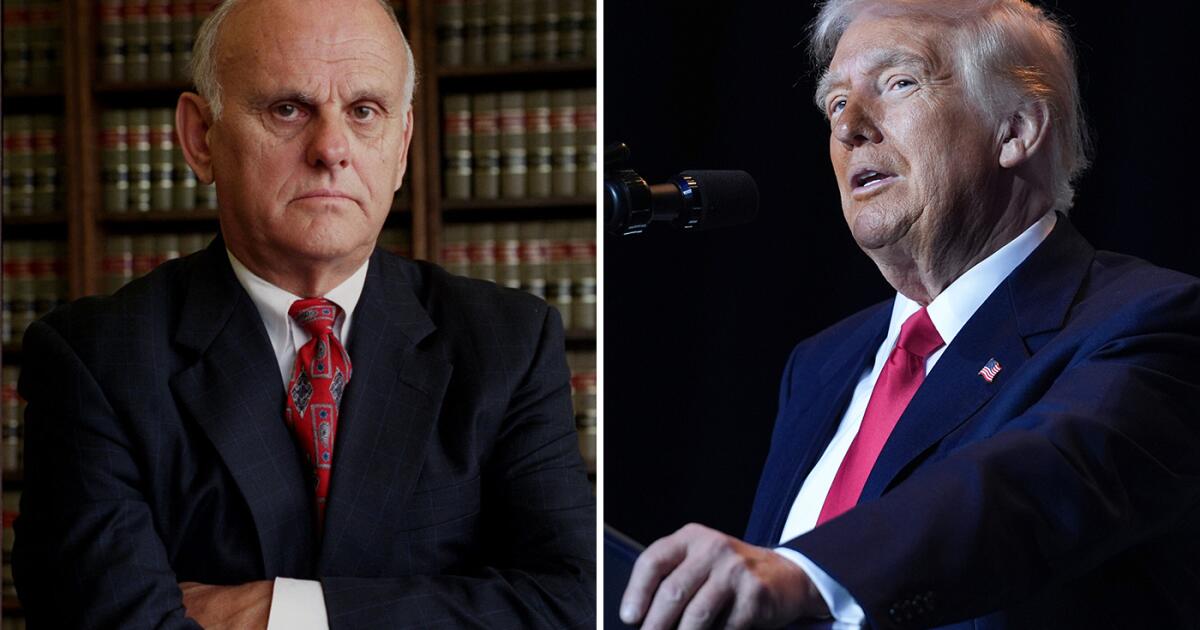

U.S. District Judge John C. Coughenour in Seattle on Thursday put Trump’s order on hold for the duration of a lawsuit brought by four states and an immigrant rights group challenging it. His ruling followed one by a federal judge in Maryland in a separate but similar case involving immigrants’ rights groups and pregnant women whose soon-to-be-born children could be affected.

Here’s a closer look at where things stand on the president’s birthright citizenship order.

Where do things stand on birthright citizenship?

The president’s executive order seeks to end the automatic grant of citizenship to children born on U.S. soil to parents who are in the country illegally or who are here on a temporary, but lawful basis such as those on student or tourist visas.

On Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Deborah Boardman in Maryland placed an injunction keeping it on hold long term, until the merits of the case are resolved, barring a successful appeal by the Trump administration.

Following a hearing on Thursday, Coughenour — a Ronald Reagan appointee who has been on the bench since 1980 — issued his own injunction. Trump is simply trying to amend the 14th Amendment — which grants citizenship to those born in the U.S. and subject to its jurisdiction — for political reasons, the judge said.

“The rule of law is, according to him, something to navigate around or something ignored, whether that be for political or personal gain,” Coughenour said. “In this courtroom and under my watch the rule of law is a bright beacon, which I intend to follow.”

Coughenour’s injunction comes two weeks after he called Trump’s order “blatantly unconstitutional” and issued a 14-day temporary restraining order blocking its implementation.

The Justice Department is expected to appeal the injunctions.

What about the other cases challenging the president’s order? In total, 22 states — including California — as well as other organizations, have sued to try to stop the executive action.

The matter before the Seattle judge involves four states: Arizona, Illinois, Oregon and Washington. It has been consolidated with a lawsuit brought by the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project. Eighteen states, led by Iowa, filed a “friend-of-the-court” brief supporting the Trump administration’s position in the case.

Another hearing is set for Friday in a Massachusetts court. That case involves a different group of 18 states challenging the order, including New Jersey, which is the lead plaintiff. Yet another challenge, brought by the American Civil Liberties Union, goes before a federal judge in New Hampshire on Monday.

What’s at issue here?

At the heart of the lawsuits is the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868 after the Civil War and the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, which held that Scott, an enslaved man, wasn’t a citizen despite having lived in a state where slavery was outlawed.

The plaintiffs argue the amendment, which holds that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside,” are indisputably citizens.

The Trump administration has asserted that children of noncitizens are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States and therefore not entitled to citizenship.

“The Constitution does not harbor a windfall clause granting American citizenship to … the children of those who have circumvented [or outright defied] federal immigration laws,” the government argued in reply to the Maryland plaintiffs’ suit.

Attorneys for the states have argued that it does — and that has been recognized since the amendment’s adoption, notably in an 1898 U.S. Supreme Court decision. That decision, United States v. Wong Kim Ark, held that the only children who did not automatically receive U.S. citizenship upon being born on U.S. soil were children of diplomats, who have allegiance to another government; enemies present in the U.S. during hostile occupation; those born on foreign ships; and those born to members of sovereign Native American tribes.

In 1924, Congress passed a separate law granting birthright citizenship to Native Americans.

The U.S. is among about 30 countries where birthright citizenship — the principle of jus soli or “right of the soil” — is applied. Most are in the Americas, and Canada and Mexico are among them.

Johnson and Catalini write for the Associated Press. Johnson reported from Seattle, Catalini from Trenton, N.J. AP writer Michael Kunzelman contributed from Greenbelt, Md.