Rep. Robert Garcia launched an investigation Monday into Los Angeles County’s emergency alert system following a succession of faulty wireless alerts that urged millions of residents to prepare to evacuate and stoked panic as deadly fires engulfed the region.

Rep. Garcia, a Long Beach Democrat who sits on the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, sent letters requesting information from Los Angeles County, Genasys Inc. — the software company contracted with the county to issue wireless emergency alerts — the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Federal Communications Commission.

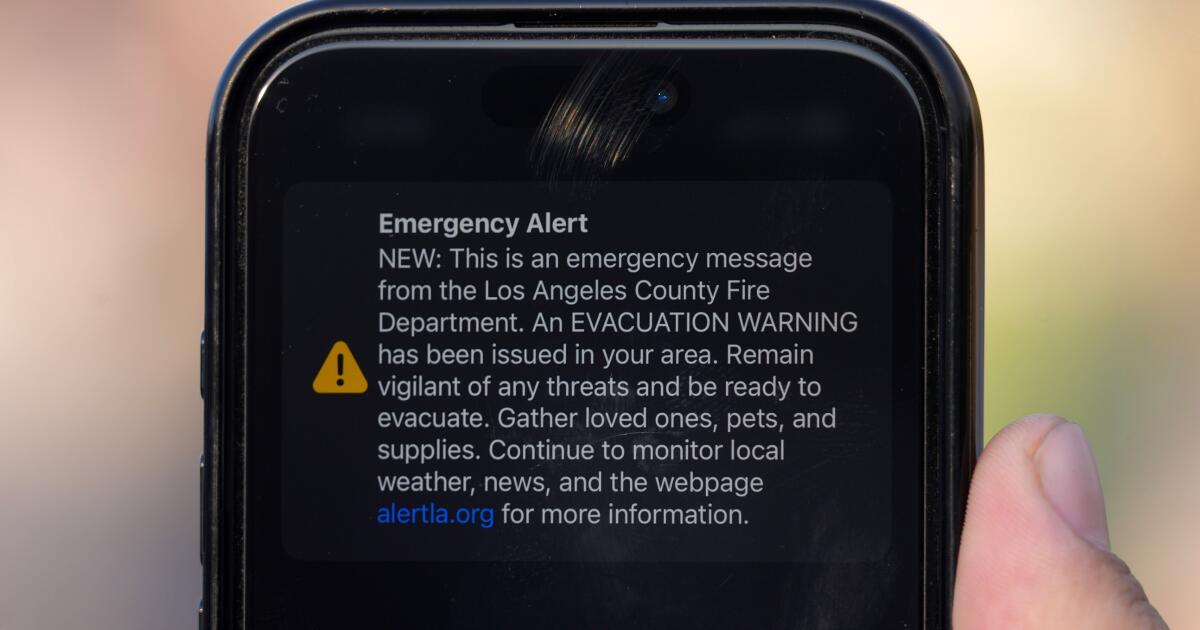

“In life-safety emergencies, appropriately timed, targeted, and clear emergency alert messages can mean the difference between life and death,” Garcia wrote. “However, unclear messages sent to the wrong locations, multiple times and after the emergency has passed, can lead to alerting fatigue and erosion of public trust.”

“In this time of intense grief, loss, and dislocation, we are working to learn all of the lessons of the past weeks, and to swiftly implement reforms to ensure they never happen again,” Garcia added.

The letters, signed by more than a dozen members of L.A.’s congressional delegation, request details on the “precise failures” that led to the erroneous alerts. Garcia wrote that his intention was to determine whether “additional statutory requirements, guidance, or regulations” are needed to prevent future false alarms.

On Jan. 9, residents across the metropolitan region of 10 million people received a wireless emergency alert urging them to prepare to evacuate. A correction was issued approximately 20 minutes later, stating the alert was sent “in ERROR.” But a stream of faulty alerts continued to sound out the following day. Residents as far away as Long Beach — more than 35 miles from any active fire — reported receiving pings on their phones.

County officials later said the alerts, meant to go out to a smaller group of residents in the Kenneth fire evacuation area, were caused by a software glitch. After switching to a different system, the county said in a statement that it was working with Genasys, FEMA and the FCC to investigate how alerts continued to ping out on phones across L.A. County.

“Due to the incorrect warning, millions who were never under any wildfire danger were unnecessarily alarmed and confused, causing distress in a dangerous time of out-of-control wildfires,” Garcia wrote to Genasys, FEMA and the FCC. “This has serious implications for public safety and well-being at a time of intense distress for our community. Further, the incident raises a serious risk that future alerts could be ignored or downplayed by more recipients, placing lives at risk.”

The letters do not mention Los Angeles County’s handling of emergency alerts and evacuation orders to Altadena residents during the Eaton fire. When flames erupted from Eaton Canyon on Jan. 7, neighborhoods on the town’s east side got evacuation orders at 7:26 p.m. But residents on the west side did not receive orders until 3:25 am — hours after fires began to blaze through their neighborhoods. All of the 17 people confirmed dead in the Eaton fire were on the town’s west side.

In a letter to Fesia Davenport, the chief executive of Los Angeles County, Garcia asks the county to provide, no later than April 1, information about how it utilizes Genasys software to provide protective communication tools and to describe the actions taken by both L.A. County and Genasys in the days after the false alarms.

Garcia also asks the county to describe its operating procedures for utilizing Genasys’ evacuation and alert software, the status of its investigation into the cause of the erroneous alerts, what issues were presented by the user interface of Genasys’ alert system, how Genasys has addressed these issues, and whether the county is continuing to use the company for its emergency alerts and messages.

After the incident, Kevin McGowan, director of L.A. County’s Office of Emergency Management, announced the county would overhaul its emergency notification systems: It would suspend its alert system operated by Genasys and switch to a separate system, operated by the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, for any future emergency alerts via cellphones.

The letter asks the county to describe the CalOES system for emergency alert messaging and how it differs from Genasys’.

A separate letter to Genasys CEO Richard S. Danforth asks the company to provide its legal contract with the county and a copy of all emails, text messages or other written communication between Genasys and county officials in the week after the alerts went out.

Garcia also asks Genasys to provide a list of all its contracts with state, tribal or local governments. It also requests the company to describe the operating procedures the county should follow for utilizing its software, what training and oversight it provides staff of public agencies of its software, and if it implements any secondary review, two-person authentication or checklists when targeting and distributing wireless alerts.

In a third letter to Tony Robinson, the senior official performing the duties of FEMA administrator, and Brendan Carr, FCC chair, Garcia asks both agencies to explain the status of the joint investigation between L.A. County and their organizations into the erroneous wireless alert messages and whether the investigation will produce a public after-action report or recommendations.

It also asks FEMA to provide a copy of the minimum requirements for state, tribal and local governments to participate in the public alert and warning system. And it asks what potential problems are posed by the use of third-party technology providers by state, tribal and local government alerting authorities.

This is a developing story and will be updated.