Book review

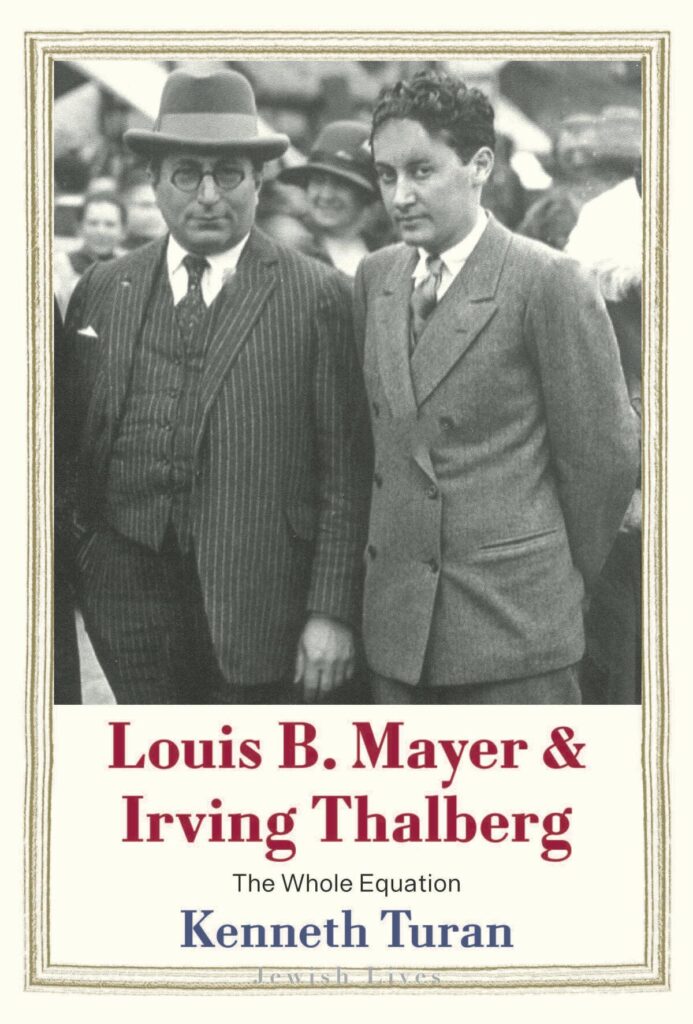

Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation

By Kenneth Turan

Yale University Press: 392 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Kenneth Turan’s splendid book about Hollywood titans Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg is the first in 50 years to tell their story in a single volume. Part of Yale University Press’ “Jewish Lives” series, “Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation” centers on the years in the 1920s and ’30s when the two men made MGM the most successful movie studio in Hollywood.

On one side of that equation was Mayer, the platonic ideal of a movie mogul, once described as “a shark that killed when it wasn’t hungry” and a man who was the highest-paid executive in the U.S. in one seven-year period. On the other was Thalberg, a sickly but energetic man whose youthfulness meant he was often mistaken for an office boy even as he oversaw and shaped behind the scenes more than 400 movies in his time at MGM. Their commitment to giving the public what they believed it wanted and to proving that motion pictures were a serious art form transformed movies.

Mayer, “a tough junkman’s son,” was born in 1884, possibly in Ukraine, and emigrated to the U.S. as a child. At 12 he was bidding at scrap-metal auctions for his father. On his journey of self-invention, he added a middle initial and claimed, with immigrant patriotism, that his birthday was July 4. Meanwhile, Thalberg, “a cosseted mama’s boy,” was born to German Jewish New Yorkers in 1899. An excellent student, he entered adulthood with a wit and emotional intelligence that would become useful for offsetting Mayer’s brasher, more impulsive behavior.

Mayer went into movies early, acquiring his first theater in 1907 and making a bundle off exhibiting the racist blockbuster “The Birth of a Nation.” He moved to L.A. when Hollywood’s industrial practices were still being developed. It was only when Adolph Zukor pioneered vertical integration at Paramount in the late 1910s that the production-distribution-exhibition business model became the standard for studios. When theater chain owner Marcus Loew brokered the merger of Mayer’s fledgling production company with two others, Mayer found himself heading up operations at a new studio called MGM.

Thalberg began his lightning career as personal secretary to Universal co-founder Carl Laemmle. His brilliance was obvious, and he rose quickly to a role with production oversight. When he clashed with Erich von Stroheim over a movie’s runtime, the director allegedly griped, “Since when does a child supervise a genius?” Thalberg was 23 when he joined Louis B. Mayer Studios as vice president, shortly before the merger that minted MGM.

Turan writes that Mayer and Thalberg’s collaboration at MGM “was arguably the most consequential in Hollywood history.” Though he tenders too many examples to cite, the “alchemy” of their working relationship was particularly evident, Turan suggests, in 1932’s “Grand Hotel.” Transcripts of story conferences demonstrate Thalberg’s detailed interventions as well as his confidence that, done right, it would prove a hit. (It won the best picture Oscar.) It’s perhaps telling that, even as Turan calls it “a high-water mark in the Thalberg-Mayer relationship,” he focuses overwhelmingly on Thalberg. Mayer holds our interest less: For all his histrionics and fainting spells — one star called him “the best actor on the lot” — he was kind of a blunt instrument, the business rather than the creative brain. Though he outlived Thalberg by 20 years, those last decades merit only a small portion of the book.

While many MGM movies haven’t stood the test of time, the studio had at least one best picture nominee annually through 1947. Mayer and Thalberg were perceptive talent scouts, notably signing Greta Garbo, whose entire Hollywood career was at MGM, alongside Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford and Clark Gable. Whether or not they made MGM the “dullest” of the studios, as film critic David Thomson claims, their commercial success was irrefutable. In MGM’s first year, only Fox Film Corp. was more profitable. By 1926, MGM was top, meriting comparison to “Athens in Greece under Pericles.” Parent company Loew’s “was the only film company to pay dividends all through the bleak years” of the Depression.

Turan does a fine job exploring how Mayer and Thalberg’s Jewishness affected their business and artistic lives. At a time of widespread antisemitism, both were cruelly caricatured and attacked for their movies’ perceived immorality — never mind Mayer’s conservative taste for buttoned-up, 19th century-style moralizing. Both men contributed to the building of legendary Hollywood rabbi Edgar Magnin’s Wilshire Boulevard Temple. Both had a strong sense of Jewish identity — Mayer tearfully recited kaddish, a Jewish prayer of mourning, on the anniversary of his mother’s death. Nevertheless, what made business sense for MGM took precedence: It was one of three studios to remain operational in Germany even after the Nazis forbade the employment of Jews.

Repeated arguments over profit percentages, Thalberg’s declining health and Mayer’s treacherous maneuvers eventually withered the men’s partnership. When Thalberg died in 1936, his relationship with Mayer was bad enough that Mayer is reported to have remarked, “Isn’t God good to me?”

Turan is well paired with his subject. He grew up with Jewish immigrant parents going to thriving Brooklyn movie palaces. He’s written about how the “tradition of Talmudic exegesis” prepared him for life as a critic. Decades of it — including more than 30 years writing for The Times — has equipped him with a breadth of reading that enables him to pepper his historical canvas with a dazzling range of perspectives. In his hands, Golden Age Hollywood bristles with backchat, and not just from obvious characters. Ever heard of Bayard Veiller? He directed MGM’s first dramatic talkie, and Turan has, naturally, read his “charming autobiography.” He’s dug through the boxes at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library. He’s read the unpublished memoir of Thalberg’s wife, Norma Shearer.

The result is a panoramic view of an era that’s fading fast in popular awareness. The dual-biography format perhaps precludes Turan going deeper on some of the seamier sides of the story, including Mayer’s alleged molestation of Judy Garland, mentioned only briefly, as well as the unforgivable intrusions of the studio system into its stars’ private lives. But as a record of a paradigm-shifting partnership, this is an entertaining, literate and beautifully crafted contribution to Hollywood history.

Charles Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, films and music.