TIJUANA — Outside the white gates that secure the entry to this Tijuana customs facility, a steppingstone to U.S. soil, migrants sat on a sidewalk in quiet disbelief this week, their futures suddenly feeling much darker and clouded in uncertainty.

Like thousands of others during the last year, they had arrived at the border to meet with U.S. officials for formal asylum interviews, appointments that many had worked months to schedule. Getting there, for some, had meant crossing the Darién Gap, a dense and treacherous jungle on the border of Colombia and Panama. Others had traversed multiple countries by bus, and yet others had crowded for months into shelters and local hotels hoping for confirmation of an asylum appointment via the mobile app, CBP One, that the Biden administration had utilized since early 2023 to ease the process of applying for asylum.

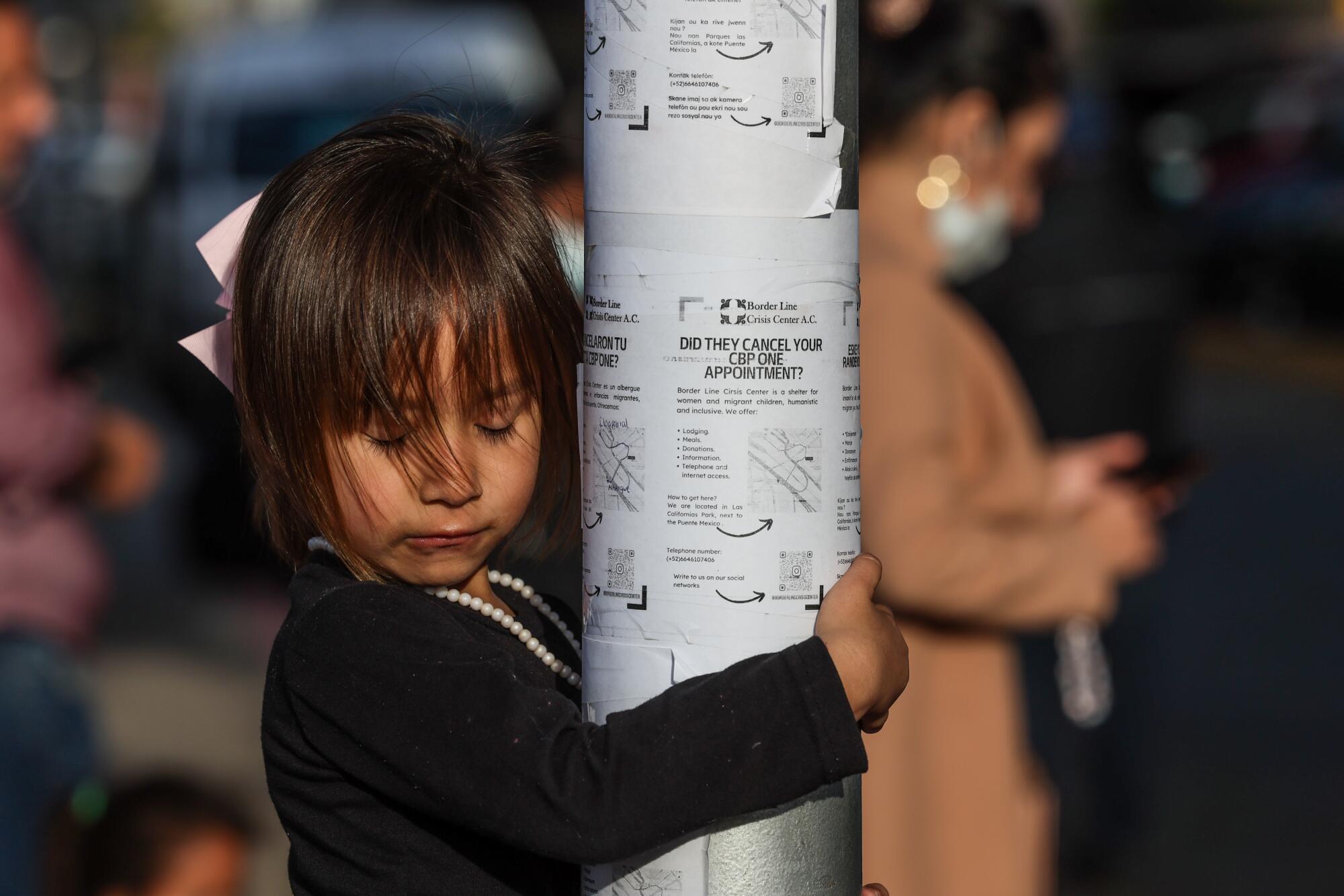

Solange Murzi passes the time as she waits with her parents outside a customs office in Tijuana.

Whatever their journey, they arrived this week to find their appointments canceled without notice or fanfare.

On Monday, shortly after President Trump took office, his administration announced it was disabling CBP One and canceling all asylum appointments. In a separate executive order, he declared migrant crossings at the southern border to be a national emergency.

“Trump signed, and everything is over,” said Roberto Canastu, 40, of Guatemala, sitting on a curb across from the customs building. Canastu had secured an appointment for 5 a.m. Tuesday — after spending more than a month loading the CBP One app every day to see whether luck would break his way with the lottery-style system. When it did, he borrowed about $9,000 to make the journey north and arrived in Tijuana the Sunday before his appointment.

But on Monday, he could not load the app on his phone. And shortly after, he was told that all appointments had been canceled. He arrived at the gate, known as El Chaparral, on Monday hoping it was untrue. Mexican officials offered no answers. On Tuesday, he arrived again to see whether something, anything, would change.

Already, the organization Border Line Crisis Center had printed fliers. “Did they cancel your CBP One appointment?” the papers asked in Spanish and English. The group offered housing, meals and information to migrants in need.

Thousands of asylum seekers discovered this week that their appointments to interview with U.S. officials at a Tijuana customs facility had been canceled.

On Tuesday, people still lingered outside the customs building, unsure what happens now. Some families sat on their luggage, appearing dazed. Children, unaware of the crisis their parents confronted, nurtured dolls and played along the fence.

“Look at all these people with their bags, with their luggage. I brought a backpack and hope,” Canastu said. He felt he could cry. “On the inside, I’m dying.”

“The only thing we can do is wait,” he added.

The scene in Tijuana was mirrored at ports of entry across the U.S.-Mexico border this week. Migrants have in effect become stranded in Mexico. Their advocates on both sides of the border are bracing for what they expect will be chaos as Trump orders mass deportations.

Mexican officials told the waiting migrants they could stay at a government-run shelter more than half an hour away by car, but they could not stay at the gate. By Tuesday evening, fewer than a dozen migrants would board a van headed for the shelter, while others left on their own, some intending to return the next day.

Children of asylum seekers chase a Trump piñata carried by an activist at a local migrant shelter.

CPB One was originally developed to help prevent backups of travelers entering the country legally. After downloading it to their phones and entering their passport information, foreign nationals could use the application to smooth their way through border crossings and airports.

In January 2023, the Biden administration expanded use of the app in a bid to help bring order to a crush of asylum seekers arriving at the southern border. The program enabled 1,450 people a day to schedule appointments at a port of entry to request asylum. In the two years since its launch, CBP One had facilitated the entry of almost 1 million people. The vast majority were interviewed, then given notices to appear in U.S. immigration courts for adjudication of their cases.

Rosaura Rubio cried as she spoke of the difficult decision to leave her native Venezuela, where she had been a political activist. She said she fled the country’s instability to give her daughters, Solange, 4, and Sofia, 10, a better future. She said she spent three months trying to secure an appointment through the CBP One app and was thrilled when they were finally accepted.

But all of that came crashing down at 11:11 a.m. Monday, when she received an email saying the appointment had been canceled.

“If they implemented the program, they should respect it,” she said. “We’re human beings.”

“We came here for something, and we believe in God. Something will happen,” says Jesus Correa, right, pictured here with his wife, Marcela Medina.

Marcela Medina, 57, her husband, Jesus Correa, 61, and their 15-year-old son were among those waiting outside the gate Wednesday, hoping their circumstances would change.

Medina cried with gratitude as she embraced a local volunteer who offered the migrants hot tea and pan dulces for breakfast. The family, from Venezuela, said they had crossed seven countries by bus after fleeing their country’s instability and violence.

They had spent five months in Mexico City, trying to register through the CBP One app, and on Jan. 2 received notification they had secured an appointment for 5 a.m. Tuesday.

Two days before, they traced the path from their hotel to the customs office to make sure they knew the way. On Monday, they watched migrants with evening appointments get turned away.

“It was not easy getting here,” said Correa, describing the violence and injuries they witnessed on their trek north. “We came here for something, and we believe in God. Something will happen, and we need to be ready, and we have to be here and make an effort.”

Asylum seekers rest in tents at the Movimiento Juventud 2000 shelter after learning that all appointments for those seeking U.S. asylum had been canceled.

Some advocates worry more migrants might consider crossing illegally, an often dangerous undertaking that still happens almost daily along the southwestern border. On Wednesday, a deportee who identified himself only by his first name, Manuel, 28, sat at a table smoking a cigarette. He carried his few belongings — eye drops, his Mexican passport, a pack of cigarettes — in a red straw bag.

Manuel said he had tried to jump the border wall Tuesday night but was caught. He hit his head on the way down. Still, he said, he intended to give it another go.

“I don’t have another choice,” he said. “Everything is possible in this life.”

Asylum seekers board a van for transport to a shelter after waiting hours outside a Tijuana customs office.

Families who had no other housing options turned to nonprofit shelters. At Movimiento Juventud 2000, several families whose appointments had been canceled were camping in tents set up inside a giant warehouse.

Outside, activist Sergio Tamai Quintero from the organization Angels without Borders lashed a Trump piñata with his belt as he sought to send a message to the U.S. president. Children, laughing, played along.

The shelter was less than half full, but director Jose Maria Garcia said he felt that would change soon.

“With this announcement from the new president, he said there will be mass deportations. What does that mean?” Garcia asked. “It means we’re going to have more deported Mexicans coming across the border, while displaced migrants continue to come north. They’ll be coming from both fronts.”

Asylum seekers cook a meal at the Templo Embajadores de Jesús shelter.