It has become a predictable talking point around baseball the last couple of offseasons, amplified every time the Dodgers sign a star on what has become an increasingly common contract for the club.

Nine times in the last five years, the Dodgers agreed to deals with significant amounts of deferred money — large portions of salaries that won’t be paid out until well into the future, after the deal is complete.

And on each occasion, the scrutiny of such maneuvers from rival fan bases has become louder and louder, with the Dodgers’ ability to put off long-term payments while reaping short-term benefits raising new fears about a competitive imbalance in a sport many worry is losing league-wide parity.

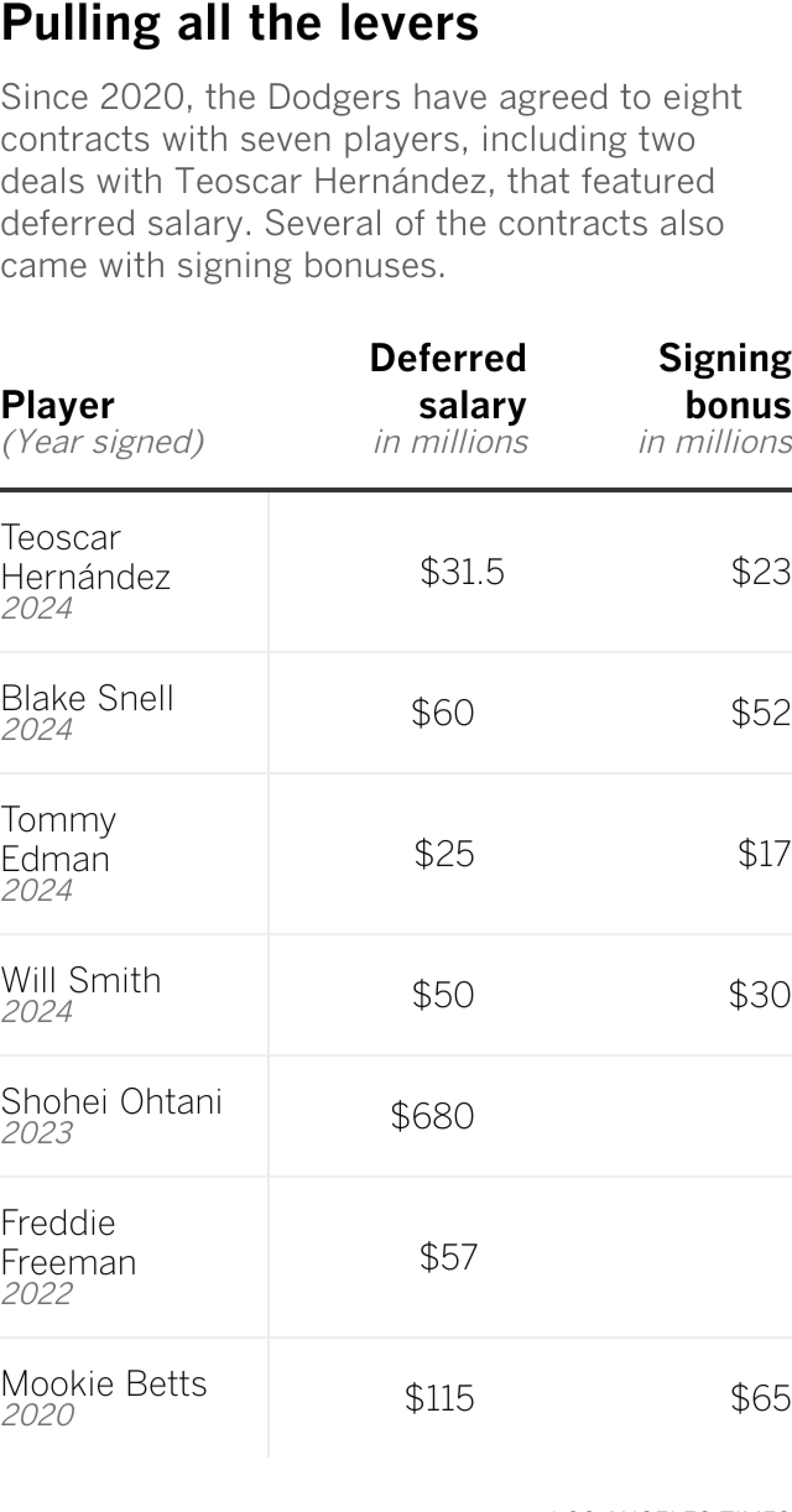

Deferred money played a prominent role in the recent signings of top free agents such as Blake Snell ($182-million contract, $60 million deferred), Tanner Scott ($72-million contract, $21 million deferred), Freddie Freeman ($162-million contract, $57 million deferred), and Teoscar Hernández (who has deferred $31.5 million of the $89.5 million guaranteed in his two Dodgers contracts).

It also was featured in extensions for Mookie Betts ($365-million contract, $115 million deferred), Will Smith ($140-million contract, $50 million deferred) and Tommy Edman ($74-million contract, $25 million deferred).

Most of all, the deferrals are what made Shohei Ohtani’s $700-million contract ($680 million deferred) such an appealing proposition for the Dodgers, a structure Ohtani personally concocted and presented to teams during his free agency last year.

As a result, the Dodgers have now accrued $1.039 billion of deferred salary over the last five years. For comparison, only the New York Mets and Boston Red Sox top even $50 million in current deferrals, according to Spotrac.

While the team’s 2025 luxury tax payroll (which is calculated using the average annual value of deals, rather than the actual amount of cash paid out each year) now stands at roughly $378 million, their use of deferrals means their actual cash payroll is only expected to be around $312 million, according to Cot’s Baseball Contracts.

Both numbers still represent MLB-highs for next season; a reminder that, for all the Dodgers have deferred of late, they are still outspending the league in present day dollars as well.

But, the imbalance has nonetheless made the Dodgers’ use of deferrals a hot-button topic around the sport — especially as they have bolstered their star-studded roster with increasingly more talent in recent offseasons.

“I think everybody’s making deferred-money jokes now,” general manager Brandon Gomes said this offseason.

In reality, however, the Dodgers’ newfound spending spree is being fueled by more than just deferred money.

For all the money they’ve kicked down the road, after all, they’ve also needed to dish out large sums to players up front.

In six of those nine deferral-laden deals over the last half-decade, the Dodgers have also included large, immediate signing bonuses to sweeten their offers to big-name players.

Snell got a $52-million bonus when he signed in November. Hernández received a $23-million bonus when he re-signed last month. Smith’s 10-year extension included a $30-million bonus. Edman’s five-year deal had a $17-million bonus. Betts’ 12-year mega-extension featured $65 million in a signing bonus (though that amount is being paid out in equal annual payments over 15 years). Scott then got a $20 million signing bonus in the deal he struck with the club.

Add other recent deals without deferrals that also included big bonuses — such as the $50 million Yoshinobu Yamamoto got in his $325-million signing, or the $10 million Tyler Glasnow got in his $136.5-million extension — and that’s $295 million in signing bonuses the Dodgers doled out over the last half-decade, using an equally beneficial tool in wooing players at levels few other teams can match.

“I don’t know if any team could do what they’re doing,” one official with a rival club said, “other than maybe the Mets or the Yankees.”

It’s a contractual double play the Dodgers have increasingly used to their advantage in recent offseasons. And while big deferrals and signing bonuses are tools available for any team to use in contract negotiations — MLB’s collective bargaining agreement places no restrictions on either in contracts — there’s a reason the Dodgers have been uniquely positioned to capitalize upon it with such regularity.

For one, the Dodgers’ decadelong dominance has made them a desired destination and, therefore, more likely to convince players to take deals with deferred money. At times, deferrals have been a sticking point in negotiations, including in Hernández’s drawn-out re-signing this winter. But on the whole, they haven’t impeded the Dodgers from acquiring top talent in recent offseasons.

In some cases, it’s been the opposite, with the high-deferral/high-bonus structure serving as the framework for each of the team’s three signings of $70 million-plus this offseason.

“It’s just a way for us to get at a deal when there’s a gap,” Gomes said.

“We have no hard and fast rule,” president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman added. “We just like to get deals done.”

The Dodgers’ monstrous revenue streams — which have only grown more flush with the arrival of Ohtani — have helped with that too, giving them more cash to burn on gaudy signing bonuses.

While deferrals lower the overall value of contracts (since money earned in the future is less valuable than money in the present), signing bonuses serve as a counterbalance, providing players with large sums they can receive in their lower-income-tax (or sometimes zero-income-tax) home states.

“We want the players and their individual representation to have as many tools in the tool bag to work with the team to find common ground, when there’s an interest in doing so,” Tony Clark, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Assn., told The Times last year of the union’s stance on deferred deals.

The Dodgers, meanwhile, benefit from such deals in two general ways.

In the short-term, the team can minimize the amount of luxury tax penalties it incurs for annually exceeding MLB’s competitive balance tax thresholds, because MLB calculates luxury tax payrolls based on the average annual value of each team’s contracts (which, again, are lowered when deferrals are involved).

And in the longer term, deferrals present a de facto investment opportunity; an especially useful tactic for a club owned by Mark Walter, whose Guggenheim Partners investment firm manages more than $335 billion in assets outside of baseball.

While MLB does require teams to “fund” future deferral payments by essentially setting money aside, a team such as the Dodgers can still have “that money go to work for you” in the meantime, as Friedman put it — funds the Dodgers seemingly have used to reinvest in the roster.

“We’re not going to wake up in 2035 and be like, ‘Oh my god, that’s right, we have this money due,’” Friedman said. “We’ll plan for it along the way.”

Shohei Ohtani, speaking with Dodgers president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman during spring training last year, agreed to defer $680 million of his 10-year, $700-million contract.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

What remains to be seen is whether the Dodgers’ use of deferrals will prompt MLB to reevaluate its rules.

Commissioner Rob Manfred voiced some caution over excessive use of deferrals in a recent interview with Chris O’Gorman of the website Questions for Cancer Research, saying that too much deferred money can become “problematic.”

“Historically, we did have one franchise, Arizona, that got itself into financial difficulties as a result of excessive deferrals,” Manfred said, referring to the financial mess the early-2000s Diamondbacks created by deferring too much salary. “We’ve strengthened our rules in terms of the funding of deferred compensation in order to avoid that kind of problem. But, you know, look, obviously the bigger the numbers get, the bigger the concern.”

Yet, the appetite for immediate change seems limited. Clark said last year that the union would defend players’ right to sign deferred deals if they want.

“For us, it’s fundamental simply making sure that the player, the individual representative and the teams that may be otherwise engaged have as many options at their disposal,” he said.

Prominent agent Scott Boras, who represented Snell during the pitcher’s negotiations this offseason, also downplayed concerns about deferrals and the competitive imbalance some worry they create.

“In sport, we want the excitement of intellect operating,” Boras said. “[If] we have rules that prevent certain owners from doing certain things, you get … what you see in the NBA and NFL. Here, you have chances for goliaths. Goliaths, I think, in the game are always good.”

There is no doubting the Dodgers’ status as a goliath now — a reality that was further crystalized this weekend when the team not only made Scott its latest deferred-contract signing, but also landed 23-year-old Japanese pitching phenom Roki Sasaki on a bargain $6.5 million contract (Sasaki was limited to such a contract because he was under the age of 25 and therefore classified as an international amateur).

And while deferrals have become the rallying cry of critics concerned about their skyrocketing spending, the mechanism is really only an expression of the team’s financial might, one of the many ways the Dodgers have turned their cash-rich business into a talent-rich team.

“I mean it’s just a lever,” Friedman argued, when pressed on the deferral topic at Snell’s introductory news conference. “There are times where [negotiating a] deal lines up in a more straightforward way. There’s times where it’s less straightforward. Including deferrals helps as a lever to find that overlap.”

When asked if he thought the Dodgers’ use of deferrals could be bad for the sport, Friedman then smirked.

“I think,” he said, “we’re rewarding our incredibly passionate fans.”