Every morning, farmers at Araromi Oke-Odo, a rural community in the Ife-South Local Government Area of Osun, South West Nigeria, tread the moist paths to their farms. They carry sickles and empty sacks, hoping to fill them with dark brown pods by evening.

One such morning for Micheal Adediji, a cocoa farmer, took a bitter turn. Arriving at his farm, he discovered that his cocoa pods worth about ₦500,000 ($323) had vanished. All that remained was his sickle, lying where he had left it.

“This is where I kept them,” said Adediji, gesturing towards an elevated part where countless pods had been processed earlier.

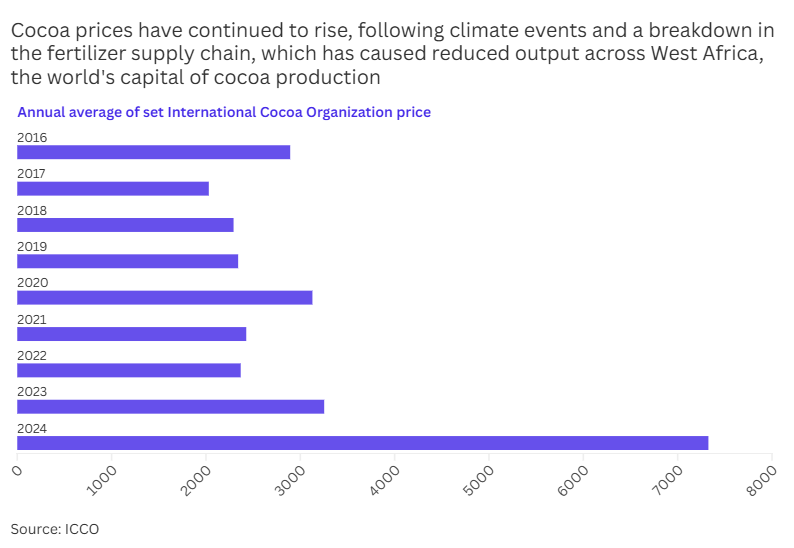

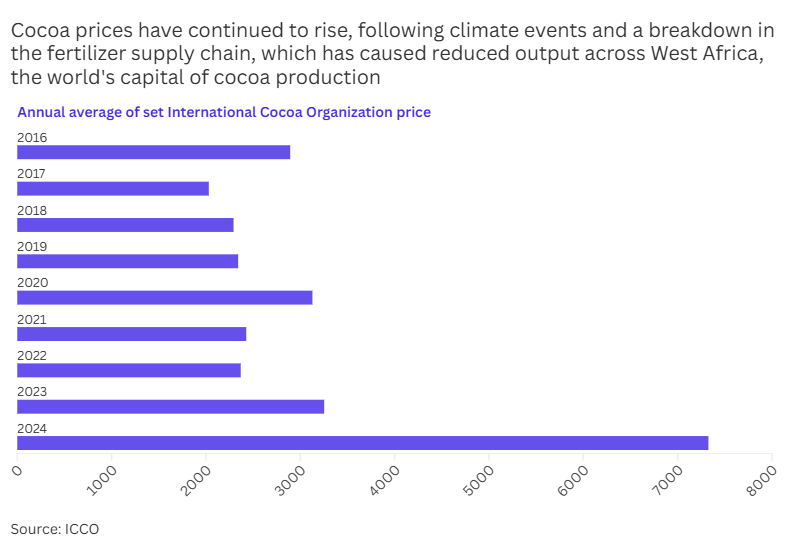

As the world continues to grapple with cocoa shortages, driven by climate change and socioeconomic conditions, which have caused a price hike, Nigerian farmers face an additional battle: the growing menace of cocoa theft.

Multiple sources revealed that, before now, farmers in the Araromi Oke-Odo community usually left their harvest behind for a week until it was done fermenting, and ready to be dried. Today, they only harvest what they can carry home the same day.

‘Cocoa farmers’ prosperity attracts thieves’

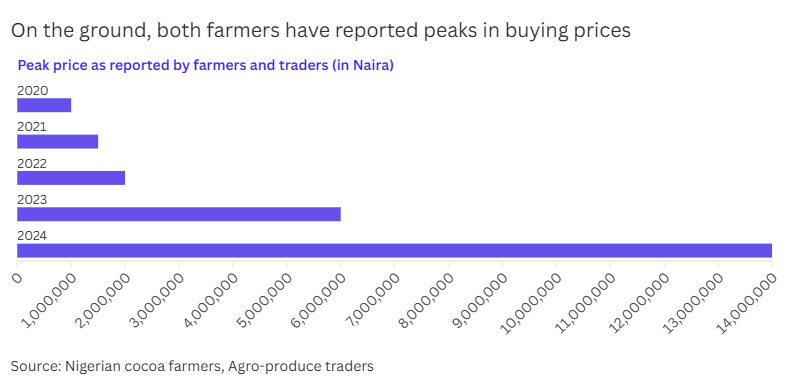

When Adediji started cocoa farming in the late 90s, the profession was wrapped in stigma. Many people saw it as a backbreaking job with minimal return. Over the years, however, it has become a lucrative business.

Farmers like Adediji have worked tirelessly to build a better life from the business. It has enabled him to acquire plots of land, a motorcycle, and a car, while also providing the basic necessities for his family.

“The business has changed for good,” Adediji said, swinging his cutlass against a tree’s dead branches. “I am able to do more financially.”

But the growing fortune of cocoa farmers like Adediji has drawn the attention of armed and unarmed thieves who now stalk farms, stealing valuable pods, and leaving farmers with devastating losses. The problem is so dire that 88.89 per cent of cocoa farmers in a southwestern state cited crop theft as their major concern, as it lowers their output and revenue.

Jamiu Omiwole, a retired village teacher, went to the farm and came back to find that the cocoa pods he left in his sitting room to air-dry had been stolen.

“Farmers put in a lot of hard work and money into the cocoa tree,” Jamiu said. “You have to fertilise the land, clear the bush, and spray the trees. Yet, the thieves are not letting us reap the fruits of our labour.”

Woman narrates ordeal

We learnt that the problem is more existential for women, who are not only deprived of economic autonomy but also see their social standing erode, undermining their influence within their communities. When cocoa is stolen, some women, especially widows who inherited their husbands’ cocoa farms, are forced to work longer hours to compensate for the losses, exacerbating their already heavy workload.

Oladayo Lateefat is one such widow. Twice in 2024, neighbours caught thieves, one of them being her worker, stealing from her farm.

“We were able to get a hold of some that have been terrorising us in April 2024,” she said. “It seems like no place is safe for our cocoa; it is stolen both indoors and on the farm. He (the thief) was one of my employees. He would return at the end of each workday to get the cocoa he had retained.”

When asked what happened to thieves caught on people’s farms, Lateefat explained that they are usually beaten and reported to local vigilantes, as the community lacks a police station. However, not all encounters with thieves end well. Villagers recall the grim fate of a man whose hand was hacked off when he tried to stop a group of thieves from stealing cocoa from his employer’s farm.

“On another occasion, a farmer was tied to a tree and made to watch as all his harvest was stolen before he was killed by armed robbers who invaded his farmland last year,” Lateefat said. Multiple sources, including local vigilantes in the community, corroborated her account.

Following the recent security threats, women farmers in the community said they try to work together, with at least one man present, to make them feel more secure. They also ensure they look out for each other’s farms.

The absence of security agents in Araromi Oke-Odo has left its about 6000 residents feeling abandoned and vulnerable, forcing them to defend themselves against attacks from armed robbers—or risk abandoning their farms altogether.

Fearing that the relentless thefts and violent attacks could lead to a breakdown in law and order, the community set up a local vigilante group, led by Oluseyi Oladosu, head of hunters in Araromi Oke-Odo.

“Whenever a thief is caught, we still have to transport them four hours to the nearest police outpost,” Oladosu explained. “Since the surge in cocoa prices and a positive change in the lives of farmers, we see different people coming into the town. We need the government’s intervention.”

Though the villagers have dedicated a building for a police station for the past four years, no police personnel have been deployed to the community. When we contacted Yemisi Opalola, spokesperson of Osun State Police Command to make enquiries about the alleged neglect of the cocoa-producing community, but she had not responded to several calls and text messages as of the time of filing this report.

Like Araromi Oke-Odo, many rural communities across Nigeria are without police officers and stations. Yet, a 2018 report revealed that over 150,000 police personnel were attached to VIPs and unauthorised persons in the country. While police authorities have repeatedly announced the withdrawal of personnel from dignitaries to address rising security challenges, the situation remains unchanged.

‘Bad roads in Araromi Oke-Odo’

Cocoa traders sourcing from Araromi Oke-Odo have also raised concerns about the neglect of the roads connecting the community to major towns. They noted that the poor condition of these roads has created a haven for criminals.

“When we turn to our elected officials for assistance, they usually say funds are insufficient,” said Abdulwahab Lawal, the traditional head of Araromi Oke-Odo. “The government must step in.”

Olawale Rasheed, spokesperson of Osun State governor, also did not respond to inquiries about the state of roads, police presence, and overall security of the village at the time of filing this report.

Rahman Sanusi, a professor of agricultural economics at the Federal University of Agriculture in Abeokuta, explained that the threats against farmers might force them to abandon the cocoa business, exacerbating the global shortage and gradual decline of the community’s economy.

“While others may have goods to sell, someone whose goods have been stolen won’t have the motivation or even the resources necessary to put back into the business,” Sanusi argued.

Until lasting solutions are found, the farmers continue to cling to the hope that their resilience, as always, will outlast challenges.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center, and is part of a series exploring the complications of Cocoa across West and Central Africa.