Indonesia’s sanitation is arguably one of the worst in the Southeast Asian region. In line with this, in 2015, Indonesia ranked second with 54 million people who still defecate in any place. This will further increase the risk of environmental pollution and the most risky is water pollution (Komarulzaman et al., 2016). In 2019, Indonesia at least 18% of the population lived without access to clean water, 80% without access to toilet water, and 98% without access to sewerage systems. This then has implications for economic losses that reach 2.3 per cent of the national GDP (Bappenas, 2019). There are still many areas in Indonesia that lack clean water and many water sources are contaminated by bacteria, whether it is due to open defecation or other chemical gases. In fact, in Java alone, the level of water hygiene needs to be improved and more water cubic centres are needed given the increasing population. Furthermore, in 2020, Bappenas issued a new standard to improve the quality of drinking water, healthy housing, and sanitation based on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) where the standard changed from ‘decent’ to ‘safe’ (Satriani et al., 2022).

A brief description of KIAT and sAIIG programmes

The roller coaster-like relationship between the two countries indicates the close and strong diplomatic relations between the two countries, especially in bilateral cooperation. This is because, indirectly, Indonesia can maintain security stability and become Australia’s liaison in the Asia-Pacific region. In response to the continuing water and sanitation problems, one of the efforts made by the Indonesian government is to collaborate with the Australian Government through the Small-scale Infrastructure Assistance for Infrastructure Grants (sAIIG) programme which is one of the specific programmes of the Kemitraan Indonesia Australia untuk Infrastruktur (KIAT) (Bappenas, 2019). KIAT itself is a collaborative initiative between the governments of Indonesia and Australia that aims to strengthen sustainable and inclusive economic growth by increasing the availability of infrastructure for all levels of society. In the process, KIAT has several special programmes, one of which is urban water and sanitation by initiating a grant programme to support the expansion of sanitation and clean water coverage with sAIIG as its implementation (KIAT, n.d.).

sAIIG is a grant program funded by the Australian government that was initiated in 2012 and is scheduled to conclude in 2024. It is subject to the oversight of Australian Aid (AusAID), which administers the allocation of funds to the Indonesian government. The disbursement of grant funds by AusAID is contingent upon the successful implementation of specified sanitation infrastructure projects outlined in the grant agreement by the local government. In alignment with Indonesia’s decentralized governance structure, sAIIG advocates for the empowerment of local governments to oversee sanitation matters. However, observations indicate that local government engagement in this domain remains limited, with numerous communities exhibiting a lack of comprehension regarding sanitation and the absence of established supporting infrastructure. Despite the program’s decentralization, the central government maintains a substantial commitment to sanitation funding. This commitment is underscored by the central government’s allocation of a greater proportion of the total budget, suggesting a potential disparity in local government awareness and engagement with environmental hygiene and health issues.

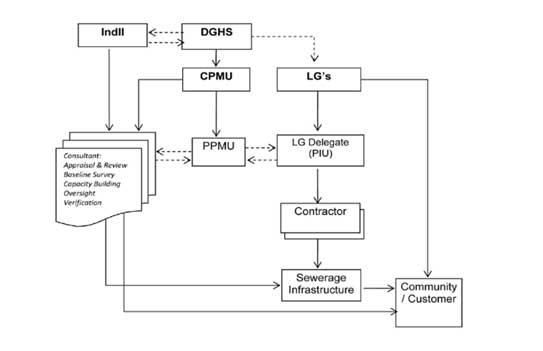

For this reason, the sAIIG programme is designed to re-engage local government in the sanitation sector by incentivising investment and also developing grants as a new means of subsidy to local government. Furthermore, the programme directly engages local governments by entering into direct agreements with local governments on grant provisions with a lengthy process. At the central government level, the programme will be managed by a dedicated coordination unit consisting of a steering and technical team through the Central Project Management Unit(CPMU) and supported by Provincial Project Management Units(PPMU). The CPMU is responsible for the administration of the sAIIG programme, from coordinating with relevant government agencies, selecting local governments to participate, to providing evaluation and monitoring the sustainability of the programme. The CPMU is also the approver of grants to be sent to local governments or not, before being signed by the Government of Indonesia and AusAID. Then, in the local government, Project Implementation Units(PIU), together with the Satuan Kerja Perangkat Daerah (SKPD) will be formed based on the decision of the Chairman of each participating local government. The PIUs will then be responsible for the broad implementation of the project, from the preparation of programmes and documents to preparing documentation for grant payment applications (AusAID, 2011).

Figure 1 Organisational Structure Chart of sAIIG (AusAID, 2011)

As part of KIAT, sAIIG specifically focuses on improving sanitation and clean water facilities. This is in line with KIAT’s main objective of strengthening sustainable and inclusive economic growth by improving infrastructure for all. Furthermore, KIAT is here to support sAIIG in its efforts to improve sanitation in Indonesia by providing a comprehensive framework. sAIIG will provide grants totalling $40 million over a three-year period to approximately 40 selected local governments to implement sanitation infrastructure using an ‘output-based’ modality. sAIIG will provide improved sanitation to approximately 90,000 households or 400,000 beneficiaries. Grants will be stipulated in a grant forwarding agreement and implementation will follow GoI systems and procedures.

sAIIG’s Success in the Construction of Sanitation Facilities

In its implementation, the sAIIG phase I programme which started in 2013-2017 was followed by 38 districts/cities and in 2017 only 28 districts/cities were granted an amendment to the Grant Forwarding Agreement (GRA) until 2020. During its implementation, sAIIG I has resulted in 23,155 SRs (house connections), which include clean water connections, sanitation, etc., in 28 districts/cities in the period 2013-2018 and as many as 14 thousand have passed verification so that local governments are entitled to receive incentives as promised (Bappenas, 2019). Furthermore, sAIIG phase II, which started in 2018-2020, provided a more tangible implementation. However, due to the lack of sources that discuss the direct implementation of the sAIIG programme, the author only found at least 2 (two) regions that have directly felt the positive impact of sAIIG. Firstly, Cimahi City has experienced a significant improvement in city sanitation with the construction of sanitation facilities sponsored by sAIIG. Since 2011, the Cimahi city government has had a comprehensive plan for sanitation in its area. In 2015, Cimahi City government had three major targets in this development, namely in wastewater, waste, and environmental drainage. In 2020, in terms of waste, the Cimahi City Government has succeeded in reducing 50% of waste generation and has exceeded the target given in 2015. Furthermore, the Cimahi city government built at least 9,000 sanitation channels and completed communal sanitation for 400 houses in two neighbourhoods in Cibabat sub-district. The sAIIG programme in the development of sanitation facilities in Cimahi City has had a specific impact on the environment, sanitation and health (Ginanjar & Harikesa, 2021).

Secondly, the success of sAIIG in the development of sanitation facilities is also seen in Sleman Regency where the Sleman government and residents have succeeded in minimising blockages in wastewater disposal by using fat catchers. However, there is no success without failure, the fat catcher sometimes experiences blockages. A quick response from DLH Sleman made this obstacle resolved quickly enough so that the use of this wastewater connection could return to normal (DLH Sleman, 2021). Looking at the success of the two cities above, the implementation of sAIIG will not be separated from the collaboration between the central government, local governments, and local communities. In addition to improving hygiene and sanitation, effective implementation of this programme can improve the quality of life of the community beyond, because, again, the basic thing that humans need to live is health and health is supported by water hygiene which is influenced by environmental cleanliness and hygienic lifestyles as well.

sAIIG Challenges in the Development of Sanitation Facilities

In addition, there are 3 (three) main challenges faced by Indonesia and local governments in the implementation of sAIIG. Firstly, the government must fulfil the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) target of increasing access to sanitation for around 17% of the population, while investing in sustainable wastewater disposal infrastructure in cities. However, existing sanitation infrastructure tends to be concentrated in commercial and institutional buildings in city centres. This means that sanitation development is only allocated to companies and for commercial purposes such as shopping malls with local governments only tasked to serve the urban poor, thus local governments under-prioritise investment in city infrastructure that can provide sustainable sanitation coverage for the growing urban population. In addition, local governments also often rely on funds from the central government budget to replace their own expenditures, and the traditional view that property owners are responsible for sewage disposal still holds strong which may discourage investment in more robust infrastructure (AusAID, 2011).

Secondly, the Peningkatan Pembangunan Sanitasi Perkotaan (PPSP) project shows ambition to increase sanitation investment by targeting significant funding from local governments. However, a key issue faced is the lack of commitment and funding from the local government for substantial sanitation infrastructure. As explained earlier, local government funding allocations for sanitation facility development are much less than those of the central government. This then leads to the central government, which has allocated large budgets for sewerage or sanitation infrastructure as a whole, being limited by the lack of local government support in allocating their own local funds or increased funds from the central government (AusAID, 2011).

Thirdly, challenges are seen in the distribution of amendments for local governments to independently manage infrastructure in their own localities. As explained earlier, only 28 districts/municipalities have received grants from the programme, while other districts/municipalities have not received similar support, creating an infrastructure gap between regions. This indicates that there are still many other regions that cannot independently manage their infrastructure.

Conclusion: Successful or not?

The cooperation between Indonesia and Australia through the sAIIG programme is one of the concrete efforts in addressing this complex sanitation infrastructure issue. The programme not only aims to improve access to sanitation and clean water, but also to build the capacity of local governments in managing sanitation infrastructure sustainably. Substantively, the sAIIG programme has achieved success, as described through the implementation in Cimahi City and Sleman Regency. However, the inclusiveness of this cooperation still needs to be addressed. By relying on the collaboration of the central government, local governments, and communities with very little intervention from third parties, such as companies or the private sector, it will be crucial to ensure that all parties involved feel heard and represented in the decision-making process and implementation of this programme. Furthermore, given that many people may be affected by poor sanitation, especially vulnerable children and women who are actively involved in water use on a daily basis, the implementation of sustainability of the sAIIG programme is clear. However, it is also important to remember that the Indonesian government cannot continuously rely on foreign aid such as this. Perhaps, in the future, the Indonesian government can run this programme independently or with little foreign assistance to prove the nation’s capability.