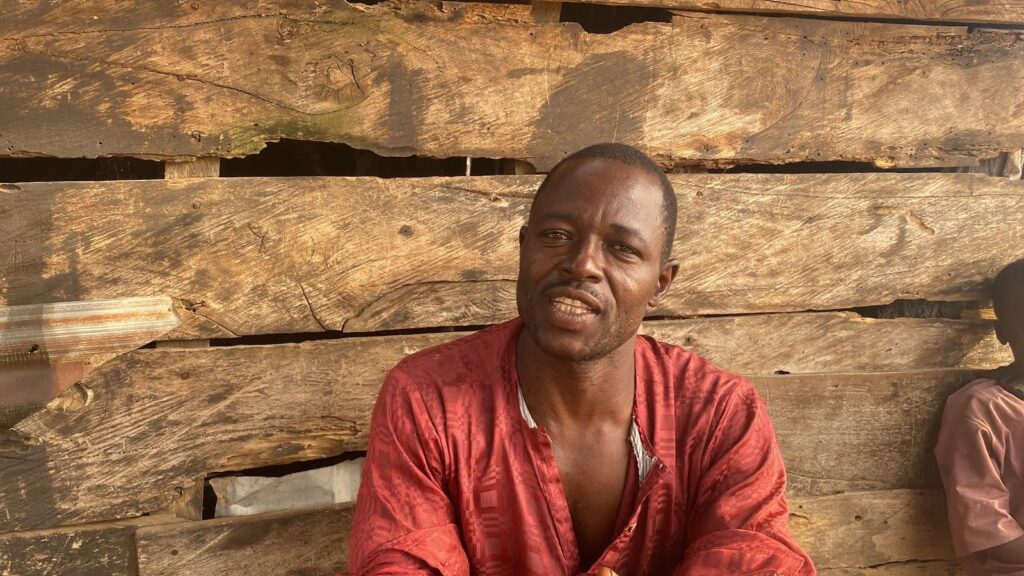

Ali Mainasara can’t forget quickly.

He badly wanted to speak about his plight, but no one would ask. A gang of terrorists raided his Kurebe village in the Shiroro area of Niger state, North-central Nigeria, and disappeared into the forests with his daughter. The villagers combed every corner of the area in search of Zainab, who was just 17 years old. Later, rumours spread like wildfire that Mainasara willingly gave his daughter to a notorious Boko Haram terrorist in exchange for his farming freedom.

Two years later, Mainasara was happy finally speaking to HumAngle about his child’s abduction. “Let’s get it right first,” he said in his local Hausa Langauge. “The terrorists invaded our village one afternoon in April 2022 and abducted some girls, including my Zainab.”

He lived like a fugitive since the ugly incident, burying his head in another village where no one knows his story. The best he knows about his daughter now is that she has been forcefully married to a Boko Haram commander somewhere on the fringes of the Alawa Forest in the state. Zainab’s unholy marriage is a euphemism for rape and sex slavery by shadowy criminals turning Nigerian forests into their fiefdoms of terror.

Due to its biodiversity richness, the Alawa Forest became the new frontier for terrorists building criminal edifices. Using the forest as a shield for their shady schemes, the criminal groups ravage towns and villages to finance their operations, raiding homes, rustling cows, imposing illegal taxes and kidnapping for ransom. They exploited the biodiversity of the wild expanses, depleting the forest.

As Zainab languishes inside the Alawa Forest, her father’s agony lingers. But Mainasara lacks the voice to tell his side of the story. Each time he remembers that his child still stays with the terrorists, his wound deepens in pain, with tears strolling down his cheeks.

“If she is with me now, I would have given her hand in marriage, or she would be in school. But since the incident, her mother has been disturbed, and she gets bonny daily. She was diagnosed with chronic hypertension. The truth is that we are in pain,” he said amid sobs.

Terrorists have built settlements on the patches of green vegetation in the Alawa forest and other national reserves across the country. “I am pleading with the government to help secure the release of my daughter so that she will be reunited with her family safely,” Zainab’s father cries.

Nigeria’s forests of thousand demons

Nigeria is said to have around 10 per cent of its landscape forested. After gaining independence in 1960, the colonial masters reportedly set aside 97,000km² (9.72%) of the country as forest reserves. Fast-forward to 2021, a Conservator General of the National Park, Ibrahim Goni, publicly admitted that about 1,129 square meters of forest reserves and national parks in the country were serving as enclaves for terrorists.

Long before he made the pronouncement, however, terrorists and criminal masterminds had established a disturbing presence in many Nigerian forest reserves. Boko Haram, for instance, had built a transnational criminal empire in Sambisa, keeping kidnap victims there for as long as their authorities were willing to pay ransom. They also conscripted men, women, and children into their criminal world, sometimes having forced marriage affairs with abducted girls.

Covered with tropical rainforest trees, forests across local government areas in the southeastern Anambra and Imo states were later named after Sambisa, following the violent activities by insurgents of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and the Eastern Security Network (ESN). The terrorists used the forests as criminal cells for kidnap victims and a coven to unleash horror on unprotected people of the states.

In northwestern and central Nigeria, the criminal escapade is scarier, with thousands of rural terrorists exploiting the forests as shelter to commit crimes. The pattern of armed conflict seems different in these regions. A cocktail of deadly violence, including cattle rustling crisis, communal war, mass murder, and kidnapping, is overwhelming the areas, with state actors struggling to conquer the criminal masterminds.

Zamfara, an epicentre of rural terrorism, has over 10,000 terrorists operating in different parts of the state, according to a study conducted by the Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto. The study stated that terrorists had killed at least 12,000 people and displaced over 50,000 as of 2021. The figures have surged since then, and the terrorists have spread cancerously into neighbouring states like Kaduna, Sokoto, and Niger, with hundreds of warlords running criminal empires.

Notably, terrorists from neighbouring countries like the Niger Republic have now found solace in many Nigerian forests. Avoiding military offensives in their countries, they run to Nigerian forests for cover, compounding the scourge of criminal enterprise in the country. In July, for instance, HumAngle revealed how dozens of foreign terrorists were infiltrating Nigerian forests through the Niger Republic borders with Sokoto.

A few months later, the Nigerian authorities announced that Lakurawa, a terrorist group using the Al-Qaeda playbook, are deeply rooted in Sokoto State. Although security operatives seemed to have swung to action immediately, the extremists had already established their cause in the remote areas, winning many of the villagers over.

On Dec. 16, however, the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) announced the arrest of at least 621 criminals using forests and national parks as hideouts. These criminals had taken over parks like Kamuku, Chad Basin, and Kainji Lake, posing a significant threat to park management and nearby communities.

A tale of three forests

Forest inhabitants commonly use traditional Bukkaru grass huts. Photo: Ibrahim Adeyemi/HumAngle.

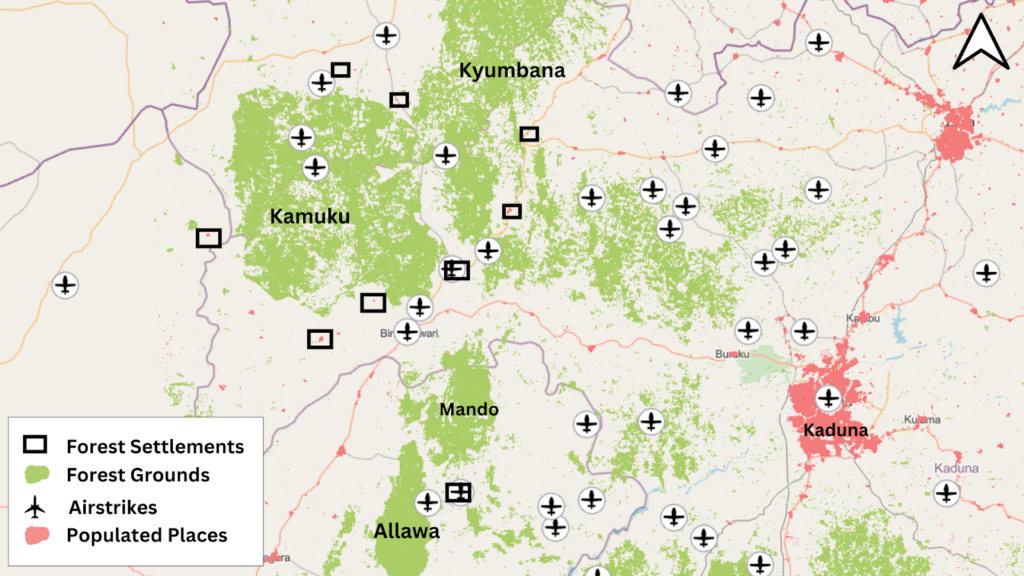

At the heart of armed violence in Nigeria, three forest reserves seem to be more notorious for sheltering terrorists: Kainji, Kamuku, and the Alawa National Parks. While the Kumuku Forest is situated in Kaduna, the Kainji and Alawa reserves are located in Niger State. But these forests share a common trait of providing wilderness cover for terrorists, diminishing Nigeria’s natural resources.

Beyond using the wilderness as a cover to evade military offensives, however, an extensive geospatial analysis of these national reserves by HumAngle shows massive forest exploits of the terrorists. Matched with on-the-ground reporting in Kaduna, Zamfara, and Niger states, the open-source investigation exposes nearly a decade-long industrial-scale logging and malfeasances by park authorities — in the name of protecting national reserves.

When we geo-located the Kainji Forest Reserve, for instance, we found a distinct road network that extends into dense forest areas, leading to isolated locations where massive deforestation is prominent. In several cases, these covert operations were conducted in cahoots with civilians, locals told HumAngle.

The geospatial assessment highlights that the primary threat to the forests and environmental stability in northwestern and central Nigeria arises from large-scale, organised extraction rather than local subsistence activities. The forest resources are intensely harvested in the wooded areas, and there are signs of small-scale mining operations in some deforested regions where soil is excavated.

Data collected on deforestation drivers in New Bussa, the local government area encompassing the Kainji forest reserve, indicate that fuelwood extraction (31.7 per cent), urbanisation (25 per cent), and logging (20 per cent) are the primary causes of forest cover loss. Subsistence farming (15.8 per cent) and population pressures (3.3 per cent) play a smaller role, while commercial farming and socio-economic factors contribute minimally. The main environmental effects include global warming (31.7 per cent) and soil erosion (24.2 per cent), showing the ecological cost of resource extraction in these areas.

Similarly, the Kamuku National Park stretches acrosses five northern states of Kaduna, Katsina, Niger, and Zamfara. The complexity of the forest makes it a natural habitat for deadly terrorists, mixing a cocktail of violence and forcing it down the throats of unarmed civilians. The Alawa forest has traits similar to those of Kamuku Park: complex, complicated, and completely out of control.

Meanwhile, Mainasara’s life hangs in the balance since his daughter vanished into the woods. The thought of his daughter being sexually enslaved in the Alawa forest hurts him. Even worse, Zainab’s mother is dying; she has mourned so much that her health deteriorates daily. But they are not alone in this: dozens of girls abducted have failed to return home since terrorists took them from their civilian villages and dragged them into the dangerous wilderness of the Alawa forest.

Rumasau Husaini, 11, was one of the enslaved girls. When she was abducted in 2022, her father, Haruna Husaini, searched for her, believing he could retrieve her by simply paying a ransom.

“When we contacted the terrorists, we asked them to return her, but they told us it was impossible to do so because she had already been taken to the forest,” Huseini recalled. “They said we should talk about her dowry, but I refused to collect it. I told them I just want my daughter.”

A walk through the terrorist camps

We found a pattern of emerging terrorist camps in the Kainji, Kamuku, and Alawa forests, with an expanding network posing threats to human existence. The setup and nature of these camps vary: sometimes, camps are situated near each other, while in other cases, they’re scattered across wider areas. Like Zamfara, where forest inhabitants commonly use traditional Bukkaru grass huts, similar structures are found on the fringes of Kainji and Alawa forests.

Unlike in other parts of northwestern states such as Zamfara, where some insurgent factions build temporary shelters deep within forested areas, reports from Kainji and surrounding forests indicate that the terror groups tend to move through forested areas, using nearby abandoned villages as temporary bases and traversing the woods to reach new targets. The scattered ruins of abandoned communities along forest axes serve as temporary waypoints rather than established bases. We found a pattern of motorcycle trails leading in and out of these abandoned sites, suggesting perpetuated habitation of the forested areas.

When kidnap victims are taken to these forests, they are often held in makeshift camps, according to sources. In the Alawa Forest, for instance, a mobile, transient approach minimises their impact on the local ecology compared to the thriving logging and mining activities in the Kainji forest. Our geospatial analysis takes us to Mando Forest, a dangerous wilderness lying between the Alawa forest in Niger state and Kamuku reserve in Kaduna.

We have recorded intelligence of terrorists from Mando Forest reserves in Kaduna travelling as far as southern Niger state by foot or with their motorcycles. Terrorists nested in this forest attack communities in Birnin Gwari, making it a pivotal transient zone for these groups. Villages in this axis have been destroyed and abandoned due to their location and proximity to the forest. The discrete emergence of motorcycle routes to some shelters within the ruins of the destroyed area is visible. Looking at the 2024 satellite data of the area, several markers show that numerous communities along these roads have been destroyed and potentially housing terror elements in these outposts of the network.

Through the roads marked in red, terrorists, especially on motorcycles, transverse between the different forest reserves. Here, there are hotspots (Red Points) that consist of abandoned communities, vulnerable ungoverned localities, and forest camps.

Satellite imagery has been instrumental in identifying the distinctions between different types of camps. Logging sites, for instance, display significant deforestation in satellite views, with freshly cut logs sometimes piled high enough to be visible from 500 meters altitude. In the northeastern part of Kainji Reserve, bordering the Kainji Dam, satellite images from this year alone show more than 20 large deforested areas with evident industrial-scale logging activity. These areas are connected by well-defined road networks, linking smaller dirt paths that facilitate access to logging sites.

HumAngle spoke to dozens of locals who are knowledgeable about the terrorists’ inner workings and forest exploits. They confirmed our geospatial reporting, noting that most of the existing herder settlements on the shore of the Alawa forest have been taken over by terrorists. They added that sometimes, the terrorists hide in these settlements to evade surveillance.

Zakariyau Abubakar, a local hunter and an unofficial ranger in the Alawa Forest, told HumAngle that he had encountered the shadowy terrorists on several occasions. He has operated in the forest for decades, he said, but the past years have been horrible for locals, with the emergence of different terror groups hiding in the wilderness to perpetrate crimes.

“Alawa is now a complete mess, a shadow of the reputable and great place it once was. Anyone who goes there now risks their life,” he said, stressing that communities near the forest reserve have turned into ungovernable spaces. “I once ran into them on the road while hunting in the wilderness. They didn’t see me. They’re usually on bikes and clad in black clothes; they are merciless and heartless.”

Using multiple satellite data, we studied the geography of the Alawa forest following insight from locals. Due to human interference, the reserve is divided into two main areas, the west (left) contains the remaining habitats where forest, land and water animals occupy, while the east (right) has already been altered by intense human activities including logging and mining.

Evidence from the sky

For months, HumAngle examined the logging activities in the Alawa and Kainji forests, following claims by local sources that terrorists work in cahoots with civilians to conduct industrial-scale logging at the expense of green vegetation. The massive tree-felling escapade is more exasperating in Kainji, with criminal masterminds taking charge of the illegal logging in the forest, according to several locals we interviewed, including tree fellers, rangers and local hunters.

The locals admitted that most times, they had to work with commandeering terrorists to cut down hundreds of trees in the lush woods. Amid the thick forest, locals take orders from criminal masterminds to let the trees bleed and share in the gains.

“The terrorists prevent loggers from going to the forest to work unless they negotiate with them,” one local told HumAngle, a claim corroborated by several others. “They once sat down and discussed what (share) they would get from us. They said they would collect all the items we got that day, and henceforth, any dealer going for operations would have to pay them.”

However, we found evidence of large-scale logging through extensive geospatial analyses, matching claims by our local sources. The scale of the deforestation gleaned from the Kainji forest shows that it is highly industrialised and sophisticated. The vast forest floors are cleared of tons of trees with geospatial markers suggesting logging activities in commercial quantities.

The image below, for instance, reveals a large-scale tree felling spree on the northwestern edge of the forest reserve. The May 2024 satellite imagery shows where the largest and most prominent trees were concentrated before they were felled, especially the point circled in red.

Yet, in another part of the reserve, we can see large woods from trees lying on the ground, signalling logs pulled up in preparation for transportation. In the western part, the circled areas suggest large numbers of logs piled on each other, showcasing a massive deforestation spree and environmental degradation.

Like Kainji, the Alawa forest reserve — an area spanning 313.38 km² in Niger state — is neighbouring several communities, including parts of Kaduna. Key settlements around the Alawa include Shadidi, Alawa town, and Gidan Umaru. Terrorists operating in this forest exhibit a more sophisticated campaign of horror, using heavy artillery weapons, land mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to cause mayhem in neighbouring communities.

Kamil Ismail, a local vigilante in Niger state, told HumAngle that he encountered the terrorists in the forest on several occasions. He noted that the criminals have mastered the geography of the forests, exploiting the lush vegetation to their advantage. Sometimes, he said, the terrorists ride dozens of motorcycles when they’re going for operations or even upon return.

“The problem we’re facing here is a combination of rural banditry and insurgency,” he said curtly. “It’ll take a strong collaboration among Nigerian military operatives to wipe out these terrorists from the forests. Many of the soldiers fighting terrorists do not know the terrain, and this gives the criminals more leverage over the military.”

The terrorists’ daily exploits have consequences, notably high-handed forest depletion, resulting in massive cover loss. The satellite images below explain this in detail.

Over ₦500 million drained for obscure projects

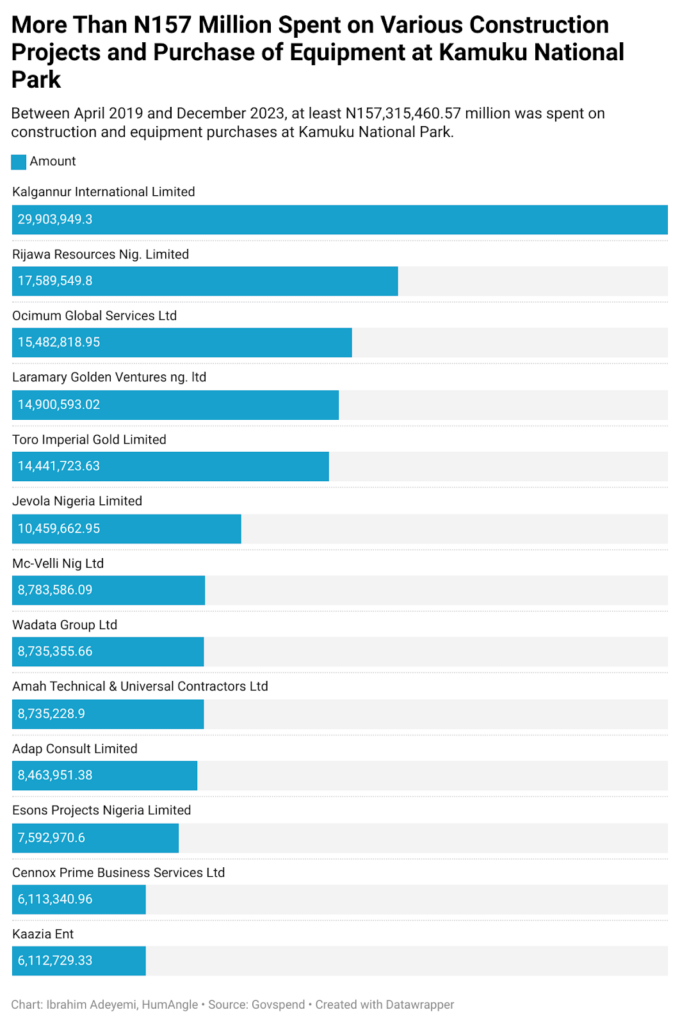

Amid escalating insecurity threatening conservation and local Nigerian communities, the National Parks Service suspended operations and research in Kainji, Chad Basin, and Kamuku national parks in 2021. Despite the suspension of operations, the authorities of the Kainji and Kamuku continued to award contracts to various companies in the name of maintaining the closed reserves.

Data from the Open Treasury Portal reveals that since 2021, the management of Kamuku and Kainji national parks have spent over half a billion (₦509,200,956.77) on various projects, including renovations, equipment purchases, boundary clearing, and purchase of communication equipment.

Between 2021 and 2023, the management of Kamuku National Park engaged 14 companies for different projects amounting to about ₦200 million (₦189,948,525.51). Some companies paid for projects include Rijawa Resources Nigeria Limited, Mc-villi Nigeria Limited, Amah Technical & Universal Contractors Limited, Laramary Golden Ventures Nigeria Ltd, Kaazia Ent, Wadata Group Ltd, and Kalgannur International Limited.

Rijawa Resources Nigeria Limited, a company incorporated in Niger state in the year 2000, was paid a total of ₦17,589,549.80 for “renovation and equipping of Kamuku head office”. The payment was made in two tranches — October 29 and November 10, 2021. One year later, the management of Kamuku National Park paid another company, Mc-villi Nigeria Limited, the sum of ₦8,783,586.09 to furnish the head office.

Amah Technical & Universal Contractors Limited, a company specialised in the supply of technical and scientific equipment on October 29, 2021, was paid the sum of ₦8,735,228.90 “for the reopening of 40 kilometres of park boundary at Kamuku.”

A similar project was awarded to a construction company, Laramary Golden Ventures Nigeria Ltd. On December 24, 2022, the company paid ₦5,959,917.21 as a 40 per cent payment for clearing 40 kilometres of [Kamuku] park boundary. On February 22, 2023, the company was paid a balance of ₦8,940,675.81.

Surprisingly, Kaazia Ent, a company specialising in building materials, was awarded a ₦6,112,729.33 contract to supply the Kamuku National Park with “communication equipment” on December 31, 2022.

On April 23, 2023, the park management engaged Wadata Group Ltd to construct a standard workshop at the park. Six months later, it also contracted Toro Imperial Gold Limited, paying the company the sum of ₦14,441,723.63 for “renovation and furnishing of charlet at Kamuku head office”.

The following month, Kalgannur International Limited, a company incorporated in Abuja in 2019, was paid ₦29,903,949.30 in two tranches to supply patrol vans. Both payments were made on December 30, 2023.

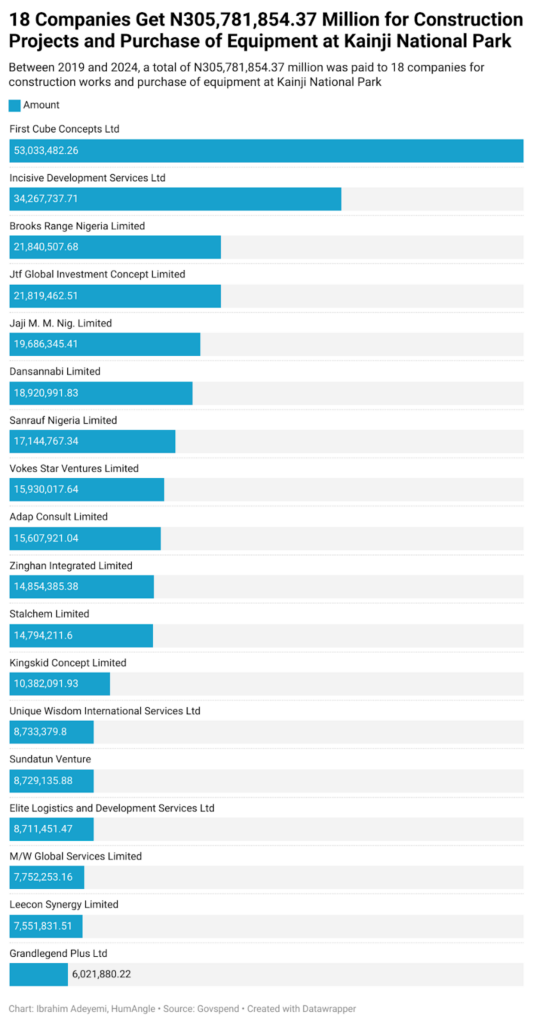

The situation is not different in Kainji National Park, where data revealed that its management had spent at least ₦319,252,431.26 on different projects since it was shut down.

Between 2021 and 2022, for instance, Dansannabi Limited, a company registered in Katsina in 2001, was paid a sum of ₦18,920,991.83 for “the re-opening of 52km Adelodun jeep track and construction of one culvert in Kainji Lake National Park”.

The sum of ₦85,912,886.46 was also spent on construction, renovation and furnishing of rangers barracks inside the Kainji National Park. The contracts were awarded to five companies — Grandlegend Plus Ltd, Jtf Global Investment Concept Ltd, Brooks Range Nigeria Ltd, Incisive Development Services Ltd and Sanrauf Nigeria Ltd — between 2022 and 2023.

Among these companies, Incisive Development Services Ltd was paid ₦13,059,232.91 million twice for the same project.

On May 20, 2024, Vokes Star Ventures Ltd was paid ₦15,930,017.64 million to procure and install CCTV cameras and trappers at the park. That same day, First Cube Concepts Ltd was paid a sum of ₦29,125,944.96 to supply patrol equipment.

A week after, Kingskid Concept Ltd was paid the sum of ₦10,382,091.93 million for the “supply of cameras and trappers” in the park. Other unspecified payments totalling ₦13,470,576.89 million were made in June 2024 by the park’s management.

HumAngle contacted officials of the National Park Service on several occasions in October and November, but their lines were either unavailable or not picked up. In the first week of December, we sent a Freedom of Information letter to the National Park Service headquarters in Abuja, asking authorities why they continue to award contracts in millions despite shutting down operations in the Kainji and Kamuku forest reserves. They have refused to respond to our request as enshrined by the Nigerian law.

When we attempted a site visitation at different project locations, we were stopped over a lack of access to the forest areas due to the operational shutdown. Locals told HumAngle that since the forest reserves were closed, no civilian could access them unless they colluded with terrorists or protected with military-grade weapons.

Zamfara, Kaduna and the River between

Traversing through the fringes of Zamfara state in our geospatial analyses, we examined the Guinea Savanna vegetation of the Kyumbana forest, a wilderness characterised by sparse trees. The thin vegetation of the forest seems to make it less appealing for logging activities compared to the Kamuku and Alawa forests.

The Kyumbana Forest hosts diverse occupants, including wildlife and wilderness settlers, some of whom are suspected of being part of terrorist camps. These settlements typically emerge in previously bare ground areas surrounded by vegetation. Over time, they leave identifiable road paths on the landscape, altering its configuration. These changes are minimal due to the settlers limited use of technology and resources.

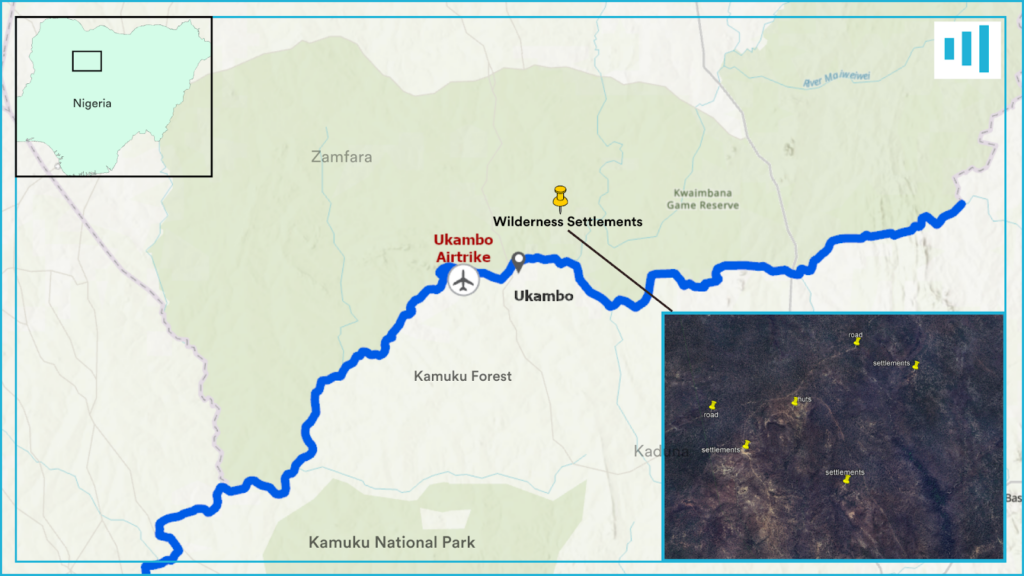

One interesting thing about Kyumbana is that it shares geographical borders with the Kamuku forest, and only a river separates it from Ukambo, a wilderness community in Kaduna state. Although it is technically situated within the official administrative boundaries of Kaduna state, the Ukambo is a stone’s throw away from the southern fringes of Zamfara’s Kyumbana forest, with only an imaginary line and official records.

Ukambo is artfully embedded in the southwestern part of the Kyumbana reserve, exemplifying a typical wilderness settlement. Satellite imagery reveals signs of airstrikes in the area, destroying villages allegedly perpetuated by terrorists dodging military operations.

The forest has settlements scattered across the landscape and connected by dirt roads and footpaths. Many of these settlements are near water sources, such as streams, which support basic domestic needs.

Suspicious settlements are visible on satellite imagery on the east of the Ukambo wilderness. The settlements feature road networks linking barren land patches within the wilderness and a nearby river for water access.

Around the Doka area — about 25 kilometres away from Ukambo — is another known hotspot for terrorist operations. Notorious terror leader Dogo Gide and his group are active in this region, often operating from neighbouring communities such as Dokka, Dansadau, and Dandala. The communities bordering the forest serve as supply hubs for both forest settlers and terrorists.

Historical satellite imagery from over a decade ago shows that many current settlements are situated on barren patches of land that predated their arrival. Roads and paths connecting these settlements have become more pronounced over time, possibly due to the cyclical presence of nomadic families.

While many settlers are engaged in subsistence activities, these settlements also serve as camps for terrorist groups. Such camps are often used to hold abductees, especially those brought from distant locations across state lines. Testimonies from kidnap victims corroborate this pattern. Towns bordering the forest provide essential supplies, as even wilderness dwellers periodically rely on nearby urban centres.

Way to go!

For too long, authorities have left Nigeria’s forests ungoverned, creating a smooth way-in for terrorists to take over. The way out of this problem, experts said, is to scale up security and surveillance in the seemingly ungovernable forest reserves and deploy technological tools to fight criminal elements killing the people and depleting the forests.

While some experts believed terrorism and insecurity are beyond a problem of “ungoverned spaces”, others urged the federal government to employ military measures to curb the forest exploits of the terrorists.

“All these approaches have failed because, in my view, they are focused on short-term fixes devoid of long-term solutions through socioeconomic interventions. The military might succeed in quashing the myriad criminal gangs but not the ethnic grievances or material frustrations of the pastoralist communities where thousands of armed bandits are recruited,” said Promise Ejiofor of the Central European University.

By law, the forest expanses fall under the government’s protection obligations. Still, experts said the Nigerian government has failed to secure them because of their huge size, lack of personnel and poor surveillance technology.

“Forest spaces must be properly governed. Special security forces, trained to work in this terrain, must be deployed,” Azeez Olaniyan of the Ekiti State University argued. “The government must also invest in technology – like CCTV surveillance systems – to monitor criminal activity. Taking these basic steps will act as a deterrent and perhaps put a stop to some of this activity.”

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Centre.

Satellite image analysis and map illustrations by Mansir Muhammed.