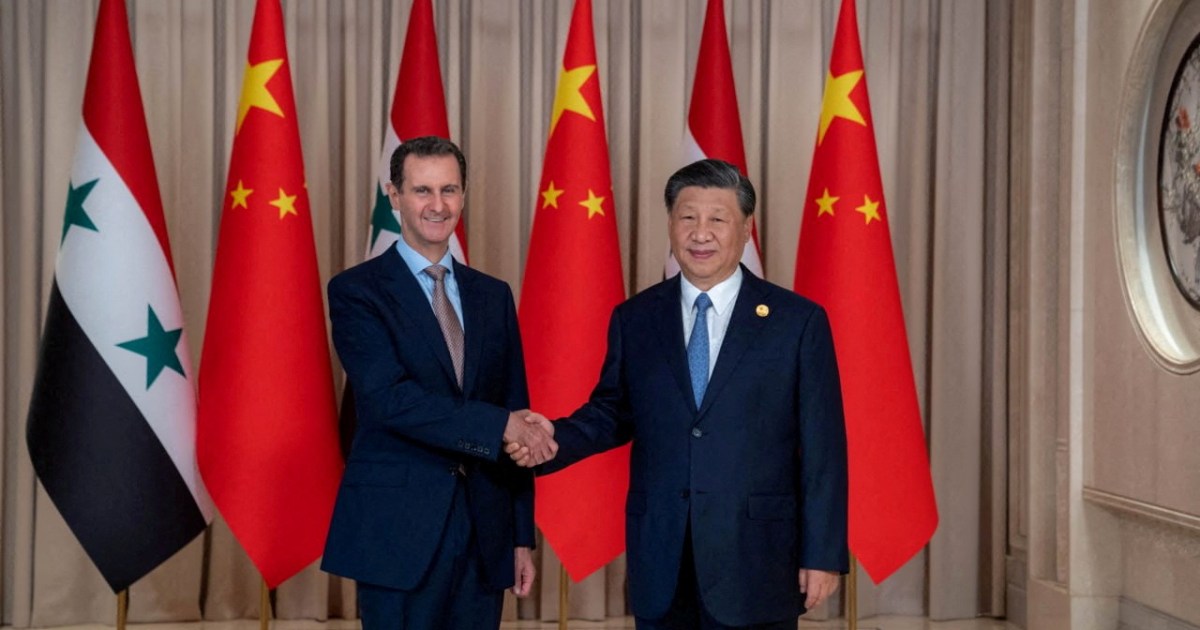

As China hosted the 19th Asian Games in September last year, President Xi Jinping welcomed Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad at a picturesque lakeside guesthouse in the eastern city of Hangzhou.

By the time Xi and al-Assad emerged from their meeting, China and Syria had struck what they called a “strategic partnership.”

A little over a year later, that partnership lies in tatters, after opposition rebel groups, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), took hold of the Syrian capital Damascus on Sunday, overthrowing al-Assad, who has fled to Russia.

Since then, China has been cautious in its response to the rapid shifts in Syria. On Monday, the Chinese foreign ministry said that a “political solution” must be found in Syria as soon as possible to restore stability.

But while that caution also captures how China has approached its relationship with Syria more broadly, al-Assad’s sudden ouster affects the world’s second-largest economy just as it is increasingly trying to expand its footprint in the Middle East, say analysts.

So what has China’s relationship with Syria been, and how will it change with new leadership in Damascus?

What happened in Syria?

The Syrian war sprung up in 2011 after al-Assad cracked down on protests against his government. The protests then developed into a rebellion, with multiple groups involved.

The governments of Russia and Iran, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and some other Iran-aligned groups in the region have backed al-Assad. The United States, Turkiye, and most Middle Eastern nations have meanwhile been critical of al-Assad, and his brutal crackdown on civilian populations and the political opposition.

On November 27, rebel groups, led by HTS, launched a major offensive from their base in the Idlib governorate in northwestern Syria. In three days, opposition fighters took Syria’s second-largest city, Aleppo. A little over a week later, they took over Damascus. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters on Monday that al-Assad was given asylum in Russia.

What has China’s relationship been with al-Assad?

Officially, China has been coy about taking sides over the future direction of Syria since the collapse of the al-Assad regime.

“The future and destiny of Syria should be decided by the Syrian people, and we hope that all the relevant parties will find a political solution to restore stability and order as soon as possible,” Mao Ning, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson said at a regular news conference on Monday.

However, while China has not had direct military involvement in the Syrian war unlike Iran and Russia, the relationship between Damascus and Beijing was cosy while al-Assad was in office.

And it was growing warmer.

The Syrian leader’s Hangzhou visit was his first official trip to the country in almost two decades. During this trip, China pledged to help al-Assad with Syria’s reconstruction after more than a decade of war, at a time when the Syrian leader was a pariah for many nations around the world.

“Faced with an international situation full of instability and uncertainty, China is willing to continue to work together with Syria, firmly support each other, promote friendly cooperation, and jointly defend international fairness and justice,” Xi told al-Assad, according to Chinese state media.

Xi added that relations between the two countries “have withstood the test of international changes”.

Diplomatic shield for al-Assad

China has used its veto power in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to block draft resolutions critical of al-Assad on 10 occasions. That’s out of 30 resolutions related to the Syrian war proposed at the UNSC.

In July 2020, for instance, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution to extend aid deliveries from Turkiye to Syria. The reason behind the veto, the countries said, was that it violated Syria’s sovereignty and that the aid should be distributed by Syrian authorities. The remaining 13 members voted for the resolution to pass.

China’s UN ambassador Zhang Jun blamed unilateral sanctions against Syria for worsening the humanitarian situation in the country. The sanctions have been placed by the United States and the European Union.

In September 2019, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution that called for a ceasefire in Syria’s Idlib, a rebel strong-hold.

“I think the Chinese, as they have done a fair few times, have gone along with the Russians for solidarity but it really was the Russian objection to this resolution,” Al Jazeera’s Diplomatic Editor James Bays said then.

Chinese money in al-Assad’s Syria

But China has been more than a sidekick to Russia in Syria. In the last decade, China ramped up its financial assistance to Syria, an indicator of its backing of al-Assad’s government.

In December 2016, the Syrian government secured a victory against the rebels when it retook the city of Aleppo. This marked a turning point in China’s aid strategy, according to the Cyprus-headquartered independent risk and development consultancy, the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR).

China’s aid to Syria jumped 100 times from roughly $500,000 in 2016 to $54m in 2017, according to COAR reports. In October 2018, China donated 800 electrical power generators to Latakia, Syria’s largest port.

Beijing has also made major, long-term investments in Syrian oil and gas – totalling about $3bn.

In 2008, China’s petrochemical enterprise Sinopec International Petroleum Exploration and Production Corporation brought Canada’s Calgary-based Tanganyika Oil company in a deal worth about $2bn. Tanganyika had a production-sharing agreement with Syria and held operating interests in two Syrian properties.

In 2009, China’s state-owned multinational company Sinochem bought British oil and gas explorer Emerald Energy, which operates in Syria, for $878m.

And in 2010, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed an agreement with Shell to acquire a 35 percent stake in Shell’s Syria unit.

Earlier this year, Syria’s Minister of Electricity Ghassan Al-Zamel confirmed a 38.2 million-euro (about $40m) contract with a Chinese company to construct a large photovoltaic plant near Syria’s western city Homs, according to Berlin-based publication, The Syria Report.

In 2022, Syria also joined Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a network of highways, ports and railroads that China is building, connecting Asia to Africa, Europe and Latin America.

Investments in Syria since its entry into the BRI have been slow, and facing the threat of secondary US sanctions, China has divested from some of its projects in Syria in recent years.

Still, China has been Syria’s third-biggest source of imports behind Turkiye and the United Arab Emirates, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity. In 2022, China’s exports to Syria stood at $424m, driven by fabric, iron and rubber tyres. Syria’s exports to China are negligible by comparison and are dominated by soap, olive oil and other vegetable products.

How will the situation in Syria affect China?

For China, “the fall of Assad does represent the loss of a diplomatic partner,” William Matthews, a senior research fellow for the Asia Pacific Programme at London-based think tank Chatham House, told Al Jazeera.

“China’s overall approach in the region has been one of pragmatic engagement,” Matthews added.

He said that while the HTS is “unlikely to be keen to work with China as a close partner, China will most likely seek to maintain engagement with the new government, including with a view to opportunities for cooperation”.

Matthews explained that China’s engagement with the Taliban in Afghanistan could provide a potential comparison “but it is too early to say so definitively”.

On January 30 this year, Xi’s government was the first to officially recognise a Taliban diplomat since the group seized power in 2021. While no country officially recognises the Taliban-led government, Beijing recognised Bilal Karimi, a former Taliban spokesman, as an official envoy to China. In 2023, many Chinese companies signed business deals with the Taliban government.

The fact that “China remains on good terms” with the Taliban, said Andrew Leung, an international and independent China strategist, suggests that “HTS is unlikely to pose a critical problem for China.” Leung, who has held many senior government positions in Hong Kong, added: “Indeed, China’s infrastructure building capacities are likely to be sought after in the war-torn Middle East.”

However, how China will respond to that demand for investments is unclear.

“Given that China has adopted a more cautious approach to overseas investments in recent years, while it is possible that China might make new investments in Syria, these will likely be calibrated against the risk of instability and potential opportunities for increased longer-term influence,” Matthews said.

He added that al-Assad’s fall poses a challenge for China because “China has growing interests in the Middle East region as an economic and development partner, and increasingly in areas such as technology and defence”.

In March 2023, China brokered a diplomatic detente between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The deal came as a surprise, after years of simmering tensions and a formal cutting of ties between the two countries in 2016.

In July this year, Beijing hosted rival Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah, alongside 12 smaller Palestinian groups. After three days of intensive talks, the groups signed a “national unity” agreement aimed at maintaining Palestinian control over Gaza after Israel’s war on the enclave is over.

According to Matthews, “the key setback for China is the risk Assad’s overthrow poses for regional stability, including the spillover of conflict into neighbouring countries”.