Welcome to the L.A. Times Book Club newsletter.

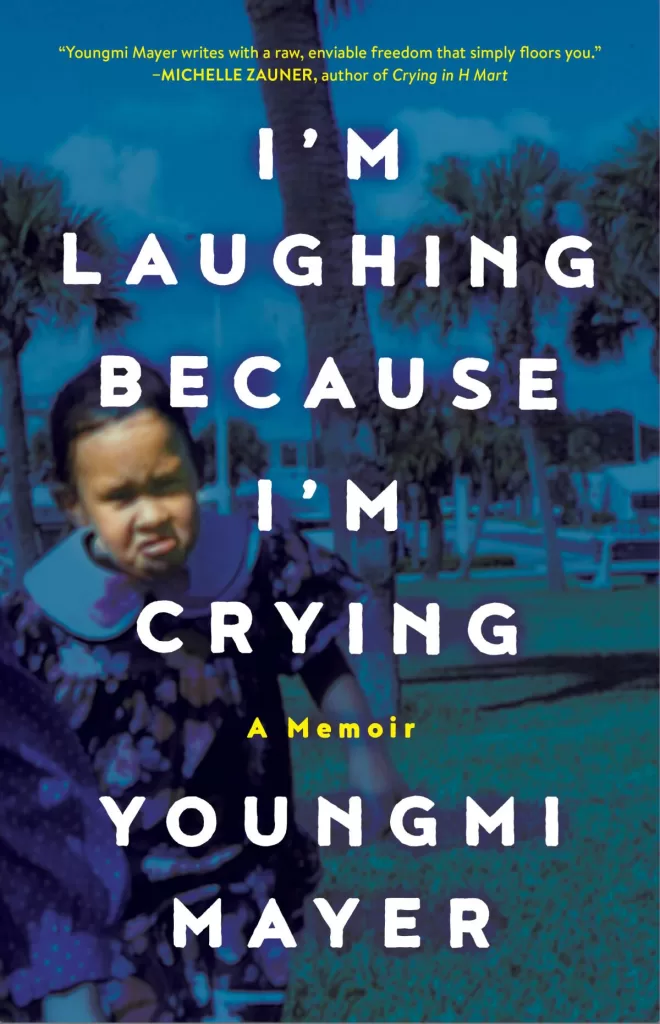

Hello, fellow readers. I’m culture critic and fervent bookworm Chris Vognar. This week we speak with comedian and first-time author Youngmi Mayer, whose new memoir “I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying” chronicles her life as a Korean American grappling with identity, trauma, history — and hilarity. We also look at recent releases reviewed by Times critics. And we recommend some other essential books by Asian American authors.

When Youngmi Mayer was growing up in South Korea, her mother would give her a warning: If you laugh while you cry, hair will grow out of your, er, butthole. It turned out this was an old belief and saying in Korean culture. “It’s like when people say if you masturbate, hair grows on your palms,” Mayer told me. “My mom used to beat my ass, and then I would cry, and then she would tell me jokes and I would laugh. But I don’t know why they would try to deter children from laughing and crying at the same time.” She wears the saying with pride: Her podcast is called “Hairy Butthole.”

“I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying” is indeed funny. Mayer writes about how her mother learned English largely because she grew besotted with Bee Gees lead singer Barry Gibb, whom she came to conflate with Jesus: “She went to worship to gawk at this man on Sundays after dancing to his music all night at a nightclub on Saturdays.” Mayer calls this singer/savior figure “Be’Jesus.”

But Mayer, whose mother is Korean and father is American, also offers trenchant and often painful observations, on growing up mixed race, the suicide crisis in South Korea, and the pervasiveness of white supremacy. “We know what it means when white people can’t tell us apart,” she writes. “It means they can throw us away.”

I spoke with Mayer about her mother’s stories and the strong possibility that her memoir will make some people angry.

Youngmi Mayer looks back on stories told to her by her mother in her new memoir.

(Little, Brown)

You write about some very serious stuff here, including the Korean suicide epidemic and the many Korean women who were murdered or disappeared in the wake of the Korean War. What pushed you in this direction?

A lot of that kind of history in other countries and other parts of the world is probably not as well known in America, because it’s just not taught and it didn’t happen here. I have gotten a lot of response from Korean Americans who are like, “I’m so glad you wrote about this, because my parents won’t talk about this for obvious reasons, and I always wonder about stuff like this.” But they just don’t really discuss it. I think it’s been helpful for them to hear somebody talking about it.

The title of your book is very appropriate. Some of these stories are both brutally funny and extremely sad, often at the same time.

All of the stories in the book that happened before I was born were told to me by my mom. And every single one of them, she told me like it was a funny story. So I grew up thinking that those are funny stories. In the book there’s a story she told me about a leper, and I think until I wrote the book, I didn’t realize that it was not funny. It was really sad. And so when I wrote the book I started getting sad about these sad stories. But before then, they were all funny to me or told to me in a funny way.

You also write about the imperative to conform in South Korea.

There’s a big part of the culture where Koreans will tell you if you’re doing something wrong. All my Korean friends talk about how if you’re walking on the wrong side of the sidewalk, or you’re wearing the wrong thing, somebody will tell you. The pressure and the fear of that becomes annoying.

You mentioned on your podcast that you’re worried your family will be angry if they read the book. But I kept thinking South Korea might get angry.

Who’s going to be mad at me? Korea, Japan, my parents. I also lived in San Francisco, and I really talk [expletive] about San Francisco, too. Everyone’s going to be so mad.

(Please note: The Times may earn a commission through links to Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.)

Newsletter

You’re reading Book Club

An exclusive look at what we’re reading, book club events and our latest author interviews.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The week(s) in books

A one-off appearance on “Family Matters” turned into a career for Jaleel White, author of “Growing Up Urkel: A Memoir.”

(James Anthony)

Ilana Masad reviews Edwin Frank’s “Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel.” Masad writes that Frank “makes the case for what, exactly, a 20th century novel is, what its authors’ methods and goals were, and how the unprecedented events of an ever more interconnected world shaped it.”

Leigh Haber reviews Maya Kessler’s sex-fueled debut novel, “Rosenfeld.” To Haber, “this mostly seductive novel would have benefited from a little less intermingling of fluids and a little more merging of souls.”

Malia Mendez reports on Los Angeles author Percival Everett winning the National Book Award for Fiction. His novel “James” reimagines “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” from the perspective of Jim. “I hope that I have written the novel that Twain did not and also could not have written,” Everett said in an August interview with the Booker Prize Foundation. “I do not view the work as a corrective, but rather I see myself in conversation with Twain.”

And Chris Vognar (c’est moi) speaks with Jaleel White, best known as super nerd Steve Urkel on the ‘90s sitcom “Family Matters,” about his new memoir “Growing Up Urkel.” Yes, he did that.

Asian American stories

A bookstore patron wanders through the aisles inside Skylight Books in Los Feliz.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Youngmi Mayer is just the latest in a long line of writers to tell vital Asian American stories. Here are some essential works for further exploration.

“The Woman Warrior” and “China Men,” by Maxine Hong Kingston: Kingston blends memoir, family history and folktale in these two seminal works of Chinese American literature.

“Dogeaters,” by Jessica Hagedorn: Hagedorn’s novel, later adapted into a play, digs into the culture and politics of 1950s Manila.

“The Big Aiiieeeee!: An anthology of Chinese American and Japanese American Literature”: A groundbreaking collection of prose, poetry, songs and excerpts from novels and plays. (I still have my copy from college).

“The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration”: An expertly edited and curated anthology from Penguin Classics, about a shameful chapter of history: The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

“The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” by Moshin Hamid: A searing portrait of a Pakistani man in New York questioning his success and just about everything else post-9/11.

That’s all for now. Until next time, keep on readin’.