OKLAHOMA CITY — A new study has found that systemic barriers to voting on tribal lands contribute to substantial disparities in Native American turnout, particularly for presidential elections.

Earlier studies have shown voter turnout for communities of color is higher in areas where their ethnic group is the majority, but the latest research found that turnout was the lowest on tribal lands that have a high concentration of Native Americans, the Brennan Center for Justice said.

“There’s something more intensely happening in Native American communities on tribal land,” said Chelsea Jones, a researcher on the study.

The study, released this week by the Brennan Center, looked at 21 states with federally recognized tribal lands that have a population of at least 5,000 and where more than 20% of residents identify as American Indian or Alaska Native. Researchers found that between 2012 and 2022, voter participation in federal elections was 7% lower in midterms and 15% lower in presidential elections among those living on tribal lands than among those living elsewhere in the same states.

Jones said the study suggests some barriers may be insurmountable in predominately Native communities due to a lack of adequate polling places or access to early and mail-in ballots.

Many residents on tribal lands have nontraditional addresses without street names or house numbers, making it even more difficult to vote by mail. The study notes that several jurisdictions will not send ballots to P.O. boxes, which many Native American voters rely on for their mail.

Little to no public transportation and long distances to polling stations that do exist on tribal lands create additional hurdles for Native American voters.

“When you think about people who live on tribal lands having to go 30, 60, 100 miles to cast a ballot, that is an extremely limiting predicament to be in,” Jones said. “These are really, truly severe barriers.”

Additionally, she said, the study found Native American voters were denied the ability to use their tribal IDs to vote in several places, including in states where doing so is legally allowed.

All of these roadblocks to the ballot can create a sense of distrust in the system, which could contribute to lower turnout, Jones said.

The Brennan Center study also highlights an ongoing issue when it comes to understanding how or why Native Americans vote: a lack of good data.

“There are immense data inequities when it comes to studying Native American communities, especially as it pertains to politics,” Jones said.

Native American communities are often overlooked when it comes to polling data, and sometimes studies that do include them don’t reflect broader trends for Indigenous voters, said Stephanie Fryberg, director of the Research for Indigenous Social Action & Equity Center, which studies systemic inequalities faced by Indigenous people.

“Generally speaking, polling is not well positioned to do a good job for Indian Country,” said Fryberg, who is also a professor of psychology at Northwestern University. “There are ideas that are held up as the gold standard about how polling works that don’t work for Indian Country because of where we live, because of how difficult it is to connect to people in our community.”

Fryberg, a member of the Tulalip Tribe in Washington State, was one of several Indigenous researchers who denounced a recent Edison Research exit poll in which 65% of Native American voters who participated said they voted for Donald Trump. The poll surveyed only 229 self-identified Native Americans, a sample size that Fryberg said is too small for an accurate reading — and none of the jurisdictions in the poll were on tribal lands.

“Right there, you’re already eliminating a powerful perspective,” she said.

The Indigenous Journalists Assn. labeled that polling data as “highly misleading and irresponsible,” saying it had led “to widespread misinformation.”

In a statement to the Associated Press, Edison Research acknowledged that the polling size was small, but said the “goal of the survey is to represent the national electorate and to have enough data to also examine large demographic and geographic subgroups.” The survey has a potential sampling margin of error of plus or minus 9%, according to the statement.

“Based on all of these factors, this data point from our survey should not be taken as a definitive word on the American Indian vote,” the statement reads.

Native Americans are not only part of an ethnic group — they also have distinct political identities as citizens of sovereign nations. Fryberg said allowing those surveyed to self-identify as Native Americans, without follow-up questions about tribal membership and specific Indigenous populations, means that data cannot accurately capture voting trends for those communities.

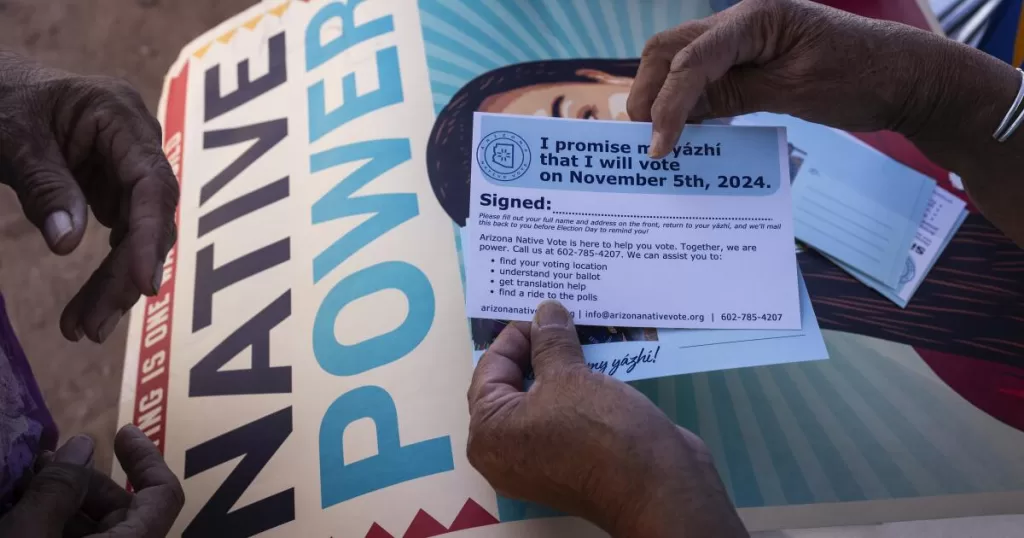

Both Fryberg and Jones said that in order to create better data and opportunities for Native Americans to vote, researchers and lawmakers would have to meet the specific needs of Indigenous communities. Jones said passage of the Native American Voting Rights Act, a bill that has stalled in Congress, would ensure equitable in-person voting options in every precinct on tribal lands.

“This is not an issue that we see across the country,” Jones said. “It’s very specific to tribal lands. So we need provisions that address that uniquely.”

Brewer writes for the Associated Press.