Article content

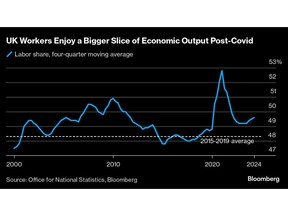

(Bloomberg) — British workers are getting a bigger slice of the economic pie than before the pandemic, signaling a shift in the balance of power away from employers after chronic labor shortages delivered unprecedented bargaining power over wages.

The share of the economy that workers take in wages has climbed to its highest level since the early 2010s, when excluding distortions during the pandemic, analysis of official statistics show. The proportion taken by profits meanwhile has been falling.

Article content

The findings indicate that instead of passing higher wages onto consumers, firms have taken a hit to their margins and are struggling to raise prices to compensate. That will comfort the Bank of England, which is seeking signs that underlying inflationary pressures are being contained as it calibrates how quickly to cut interest rates.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said the labor share could be sustained if wage growth settles above pre-Covid levels.

“It’s being driven by wage growth really, so before the pandemic, wage growth was unusually low by historical standards,” he said. “But since the pandemic wage growth has gone up quite a lot. It’s still unusually high.”

The figures also raise more doubts over claims of “greedflation,” a hotly debated topic at the height of the energy-price shock when firms were accused of ripping off customers by using the cover of inflation to raise prices more than they needed.

In practice, both businesses and workers have sought to recover income lost to the steep increase in prices triggered first by pandemic supply disruptions and then by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which sent energy and food costs soaring.

Article content

Workers have been helped by a surge in health-related inactivity that has left sectors from construction to hospitality struggling to fill vacancies. Regular wage growth hit around 8% little more than a year ago and is still almost 5%, while pay is once again growing in real terms.

The budget last month threatens to tip the scales further in favor of workers, with the Labour government announcing another hefty increase in the minimum wage and a £26 billion ($32.9 billion) increase in the national insurance payroll levy paid by employers.

The labor share had declined before the pandemic during a decade marred by stagnant real wages following the global financial crisis, falling to 47.7% of gross domestic product in 2017. It has recently settled at just under 50%, reversing some of the sharp decline seen in the last 50 years.

Firms may be taking a hit to their profits because a weak economy means their pricing power is not strong enough to pass on higher wage bills to consumers. Calculations by the Bank of England suggest the profit share has fallen to its lowest level since 2007.

Article content

The central bank pointed to evidence of profit margins being squeezed in its Monetary Policy Report earlier this month, highlighting dwindling cash reserves for smaller firms. It said there is a risk this trend could result into firms laying off workers, adding that consumer-facing services, such as retail and hospitality, are struggling to pass on higher costs due to subdued demand.

Benjamin Caswell, senior economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said it is too early to say whether the uptick in the labor share was the start of a trend.

“It’s something to keep an eye on, especially over the next few years as we see strong wage growth and as we see the measures being announced in the budget,” he said. “It will be interesting to see if the labor share does budge based on some of these announcements that we saw in the budget last month.”

Share this article in your social network