Gathered on a sunny morning in Los Angeles on Wednesday, a coalition of criminal justice reform advocates urged voters to pass Proposition 6 and finally rid California of slavery nearly 175 years after it joined the union — as a free state.

“We’re here to confront the uncomfortable truth that in our beautiful, great state of California, slavery still exists in our Constitution,” Tanisha Cannon, managing director of Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, told the crowd of supporters.

Her message was part of a broader campaign pitching support for Proposition 6 as a vote to “end slavery.” Yet according to the official state voter guide, Proposition 6 has nothing to do with slavery.

Instead, the measure asks voters whether to remove a provision in the California Constitution that uses language similar to the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution allowing jails and prisons to use “involuntary servitude” as a punishment for crime. If it passes, Proposition 6 would ban that practice, effectively putting an end to mandatory work assignments for prisoners.

Proposition 6 proponents say there is no difference between slavery and involuntary servitude in prisons because inmates typically have no say over their job assignments and often face disciplinary action if they refuse to work. And, they argue, today’s prison labor industry is an extension of a law California passed soon after joining the union in 1850 that criminalized fugitive slaves and sent them back to plantations in the South.

“Involuntary servitude is slavery by another name,” Cannon said. “Prop. 6 will finally end that cruel practice.”

Despite efforts to peg Proposition 6 as a simple anti-slavery measure, some voters aren’t reading it that way.

Only 41% of likely voters said they planned to vote for Proposition 6, according to a recent Public Policy Institute of California poll. One of the surveyed respondents, Greg Schulter, a registered Republican in Oceanside, said Proposition 6 was “way down on the bottom of importance.”

“We’re already spending tens of thousands of dollars to incarcerate somebody, I mean it’s astronomical,” Schulter said. “Working in the laundry, working in the kitchen, things like that, it’s legitimate work. It needs to be done by somebody. And it doesn’t make sense to pay a civilian $20 an hour for work they can do.”

The campaign supporting Proposition 6 has raised roughly $2 million, a pittance in a huge state with multiple expensive advertising markets. No formal opposition has been filed against the measure or money spent to defeat it.

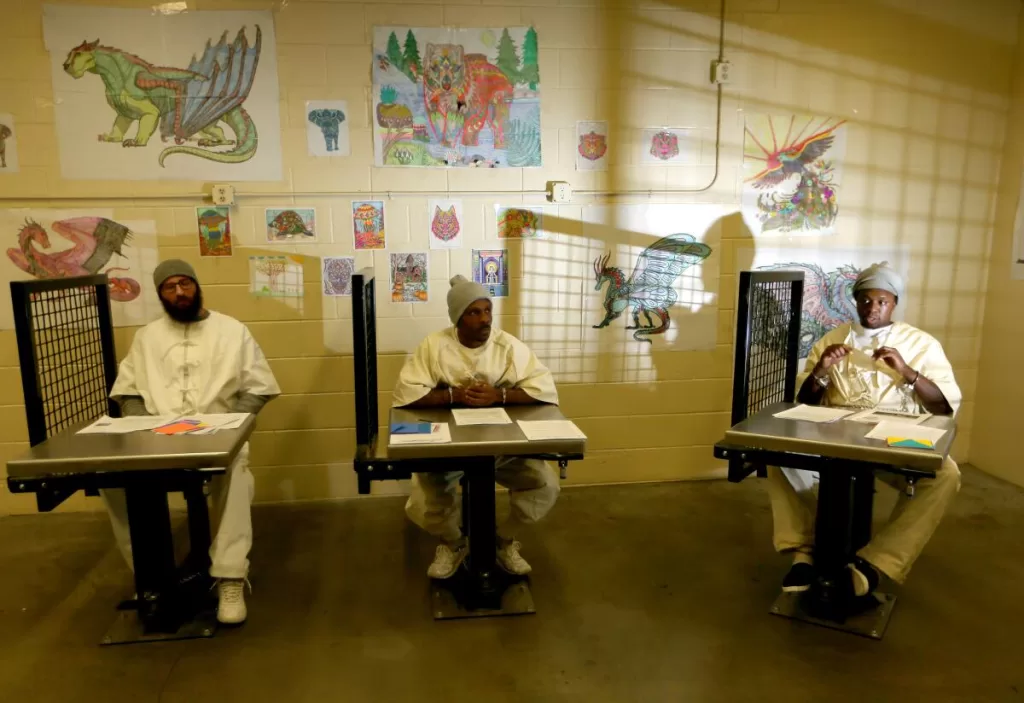

Prisoners attend a class for mental health at California State Prison, Sacramento, in 2023.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Supporters say Proposition 6 would allow incarcerated people to focus more on their rehabilitation by freeing up time in their schedules to enroll in classes that focus on mental health, substance use disorders, anger management and a variety of other self-improvement programs that better prepare them for life after prison.

“When we prioritize work, which is what our current system does … it limits those that are in our carceral system to have personal growth, to successfully reintegrate,” said Assemblymember Lori D. Wilson, a Suisun City Democrat who chairs the California Legislative Black Caucus and wrote the legislation that put Proposition 6 on the ballot.

The caucus backed a recommendation by the California Reparations Task Force to end forced prison labor as a way to address the “ongoing and compounding harms experienced by African Americans as a result of slavery and its lingering effects on American society today.”

The measure doesn’t mandate wages or outline working conditions, details the Legislature, the governor and prison officials may begin to negotiate if the measure passes.

Nearly 60,000 prisoners have job assignments, according to Terri Hardy, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Assignments include service dog training, construction work, clerking positions, computer coding, hospice care and janitorial jobs.

Approximately 5,700 prisoners have work assignments under the California Prison Industry, which runs factories that employ incarcerated people to build office furniture, make license plates and manufacture other items that are sold to state agencies.

Most jobs pay less than a dollar per hour, while a select few offer higher wages. Inmate firefighters, for example, are in some cases paid up to $10 per day.

Last year, prison officials announced plans to nearly double most hourly wages for incarcerated workers. Unpaid work assignments were also eliminated, Hardy said, and most jobs will transition to part-time positions.

Some proponents worry that voters might be confused because the ballot measure includes the term “involuntary servitude” rather than “slavery.” Other states that passed similar measures, including Oregon, Tennessee, Colorado and Nebraska, typically included the term “slavery” in the official language, though several of those propositions did little to affect prison labor.

Jay Jordan, founding partner of the advocacy organization Center for Social Good and a longtime criminal justice reform activist in California, said he understands why voters might be skeptical of eliminating job requirements. But he said most prisoners want to work, and that won’t change if Proposition 6 passes.

The measure would instead allow people to work part-time and use the rest of their days attending classes that will better prepare them to successfully return to their home communities, Jordan said. Besides, he added, the prisons don’t have enough jobs for the roughly 94,000 incarcerated people in California, nor the necessary number of rehabilitative programs. So many inmates already sit around without anything productive to occupy their time, he said.

Jordan spent seven years in prison on a robbery charge from when he was a teenager. He said he spent much of that time painting truck beds for Caltrans, making roughly 6 cents an hour, or $14 per month. A good chunk of that money went to paying restitution, while the remainder helped him stockpile cheap soups from the canteen.

Jordan said it took more than six years to finally land in programs that helped address his problems with substance use and anger management.

“I actually got worse,” Jordan said of his time in prison. “Let’s create something that actually works.”