Welcome to the L.A. Times Book Club newsletter.

Hello, fellow readers. I’m culture critic, fervent bookworm and hoops head Chris Vognar.

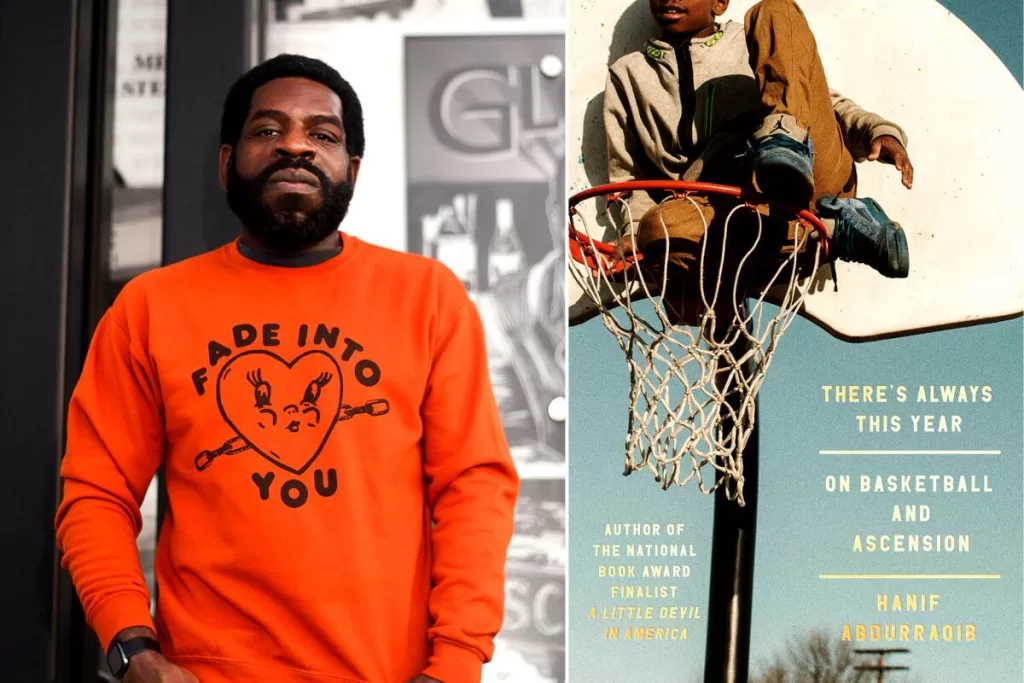

This week we speak with poet and essayist Hanif Abdurraqib about his new book, “There’s Always This Year,” which looks at basketball, place and mortality. We also look at some recent releases reviewed by Times critics. And, in honor of Abdurraqib and the freshly dawned basketball season (huzzah!), we recommend some great hoops books from years past.

“There’s a musical, orchestral nature to being able to control the game to a degree where someone gets to be more free than they were a moment ago,” says writer Hanif Abdurraqib.

(Kendra Bryant; Random House)

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, an essayist and a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant winner. He is also deeply passionate about basketball. Growing up in Columbus, Ohio, he would often trek over to Akron with his friends to marvel at a high school phenom named LeBron James. In his latest book, “There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension,” he recalls seeing “He Who Would Be King, climbing endlessly on the air during warmups, or flinging passes through impossible slivers of unoccupied space.”

But “There’s Always This Year” is about far more than one player, or even the sport he plays. It’s about the passage of time, the importance of place, fathers and sons, and the inevitability of death. It’s about love for the city. It is very much the work of a poet, and a great one at that.

As the NBA season gets underway, I spoke with Abdurraqib about everyone’s favorite Los Angeles Laker and other matters close to his heart.

What was the seed of “There’s Always This Year”?

I’m around the same age as LeBron James, and to have been there during that time is a very unique thing that a lot of people don’t have access to. A lot of people don’t have a window into the world that was Ohio in the era of LeBron James as a high schooler. I felt I had to write about that. But to me there was nothing really transcendent or transformative in that. That seemed to me like a good porch conversation but not a good page conversation.

So I found that the better angle for the book was thinking about LeBron James as an immortal figure, as he has been touted, and to kind of lens that against my realizations of my own mortality and the counting down of time, and all of these things that feel to me urgent and aligned with watching someone ascend for as long as I’ve watched LeBron James ascend. The book very quickly became about the passage of time.

Speaking of LeBron and the passage of time, there was an extraordinary moment in the Lakers’ season opener last week when he entered the game with his son and rookie teammate, Bronny. No father and son had ever played together in the NBA.

That was a great moment, and I’m glad the Lakers got it out of the way early in the season because I think it would have been hovering for a long time if it didn’t happen. I’m just thankful that I got to see it. I think it’s a testament to the longevity of LeBron, and I think people are just now maybe starting to grasp a little bit that he will be gone one day. It might not be the end of this year or even the end of next year, but we’re not going to have him in the NBA forever, and there’s a void there that’ll be left.

You are a poet, and you’ve written this great book about basketball. Where do you see poetry in the game?

The thing that intrigues me most is watching players move off the ball. I love watching Stephen Curry run around and fight for slivers of daylight through the bodies. I love motion offenses where people are running off multiple screens. I think there’s a musical, orchestral nature to being able to control the game to a degree where someone gets to be more free than they were a moment ago. Movement off the ball is the most intriguing and most beautiful part of the sport to me.

(Please note: The Times may earn a commission through links to Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.)

Newsletter

You’re reading Book Club

An exclusive look at what we’re reading, book club events and our latest author interviews.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The week(s) in books

Former Sports Illustrated journalist Melissa Ludtke shares behind-the-scenes stories of her fight for gender equity in her new memoir, “Locker Room Talk,” including the time the support of Dodgers pitcher Tommy John prompted the MLB to ban female reporters in the clubhouse.

(Greenawalt/Associated Press)

Margot Mifflin reviews “Gather Me: A Memoir in Praise of the Books That Saved Me,” by Well-Read Black Girl book club creator Glory Edim. Mifflin writes that the book delivers “a dramatic life story full of hairpin turns and interwoven leitmotifs that might seem ingeniously crafted if it weren’t all true.”

Lorraine Berry reviews Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz’s “The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America.” As Berry writes, the book “amplifies the accounts of many who have been affected by a flawed one-size-fits-all notion of identity.”

Chris Vognar — yo, right here — reviews Tom Clavin’s “Bandit Heaven,” which takes us inside the hideouts of late-19th century outlaws. As Clavin describes, the violence of the period often was perpetrated by consortiums of big land owners intent on swallowing up their smaller competition.

Plus, an excerpt from Melissa Ludtke’s new book “Locker Room Talk,” in which the author, a pioneer in securing equal access to women sports journalists, recalls how the Dodgers supported her right to report from their locker room during the 1977 World Series (before then-MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn said nah, not so much).

Further hoops reading

Kareem Abdul–Jabbar restrains Magic Johnson from going after the ref, as a technical foul was called on Magic in 1985.

(Joe Kennedy / Los Angeles Times)

As “There’s Always This Year” shows, the best basketball books cover terrain far broader than basketball. Here are some classic titles to whet your appetite for the season ahead.

“The Breaks of the Game” by David Halberstam: Halberstam could write brilliantly about almost anything. Here he applies his reportorial and observational powers to the ill-fated 1979-80 season of the Portland Trailblazers, reeling from the injuries of star center Bill Walton.

“Boys Among Men” by Jonathan Abrams: Abrams provides an incisive look at the generation of high school hoops stars who jumped straight to the NBA, including LeBron James and Lakers superstar Kobe Bryant.

“Black Ball” by Theresa Runstedtler: Runstedtler, a sports scholar who used to dance for the Toronto Raptors, looks at the 1970s NBA players who led the league toward a more socially conscious awareness of Black pride and showmanship.

“Showtime” by Jeff Pearlman: The basis for the HBO series widely criticized for playing fast and loose with the facts, Pearlman’s book delivers a lively look inside the ’80s Lakers dynasty.

“Blood in the Garden” by Chris Herring: From the opposite coast, the bruises and lunch-bucket brutality of the ’90s New York Knicks.

And a pick from Abdurraqib: “’Hoops,’ by Walter Dean Myers, was the first basketball book I loved,” he says. “I just love the way he writes the game, and I love the way he writes the architecture and landscape of a place where the game happens. My book is mostly about place, and I think I am pulling from Myers in a great way.”

Thus ends this week’s newsletter. Happy reading, remember to play defense, and we’ll see you next time.