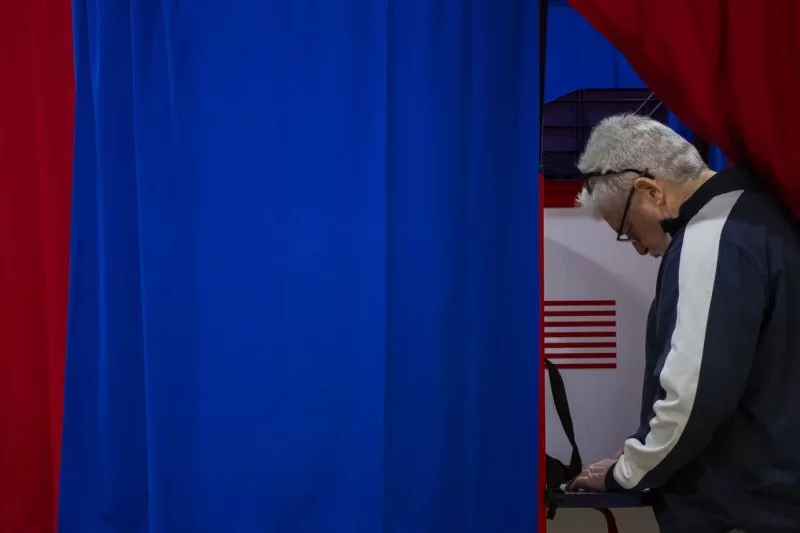

Voters cast their ballots in the New Hampshire Primary at a voting site at Pinkerton Academy in Derry, N.H., on Jan. 23. File Photo by Amanda Sabga/UPI |

License PhotoOct. 25 (UPI) — Ranked choice voting will appear on the ballot in six states and Washington on Nov. 5, possibly changing how those states administer elections.

Voters in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Washington, D.C., will vote on propositions to adopt ranked choice voting for primaries, local, state and federal elections. Missouri will vote on an amendment to pre-empt and effectively ban ranked choice voting. Alaska will vote on repealing ranked choice voting after approving it in the 2020 election.

Ranked choice voting tasks voters with selecting their preferences for office in order. A candidate must receive more than 50% of the first-choice votes to win.

If a candidate does not receive 50% of the vote in the first ballot, the election moves through rounds, eliminating the candidate that earned the fewest votes, until a candidate reaches the 50% threshold, making second place votes critical in determining who moves on.

Voters may still choose to select only one candidate.

Claims and research

Proponents of ranked choice voting believe it can improve the electoral process over the current “pick one” system.

Deb Otis, director of research and policy for FairVote, told UPI candidates are incentivized to focus more on policy when campaigning.

“There is less mudslinging and negative campaigning,” Otis said. “Going really negative can cost you second-choice votes.”

Otis adds that ranked choice voting gives minority populations more voice and levels the playing field for a more diverse and representative slate of candidates to pursue office.

Larry Jacobs, professor of politics at the University of Minnesota, conducted a meta review of ranked choice voting, reviewing a compilation of research. He told UPI that there is little research to support the claims made by ranked choice supporters. In the cases of increasing participation by minority populations and those populations being better represented, the opposite is often true.

Jacobs’ research finds that people of color, with less education, lower incomes or a combination of these factors tend to participate less in ranked choice voting elections than people who are White, have more education and earn higher incomes.

“Those who are White, well educated and have higher incomes are benefitting,” Jacobs said. “That’s what’s adding to the question about whether ranked choice voting, as well intentioned as it is, is contributing to political inequality.”

One of the main issues Jacobs observes with ranked choice voting is that it requires voters to be more dialed in to the many political campaigns and policy issues they will be voting on. They must also have a clear idea about their own positions.

“That is cognitively taxing. I don’t think there’s a way around that,” he said. “Frankly, at the university, a lot of my colleagues are very excited about ranked choice voting. I understand why. It’s a type of voting that caters to those that are in the knowledge industry.”

Cambridge, Mass., has the longest-running ranked choice voting election in the United States. It has been using this method to elect its city council for more than 80 years.

Charles Stewart III is a resident of Cambridge. He is also a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and director of the MIT Election Data and Science Lab.

“Eventually the political system does adapt to whatever election system you have,” Stewart told UPI. “However it adapts primarily around overcoming this information deficit.”

Stewart believes using this voting method in “lower stakes” local elections would be the best way to get voters familiar with it. The challenge is that there is less information easily available to voters about the nuances between candidates and policies when compared to the highest stakes elections like that of the president and members of the U.S. Congress. This is where the information deficit he refers to comes into play.

“With most reforms, advocates oversell the possibilities about what the results are likely to be,” Stewart said. “The research findings are mixed with respect to what the claims are, which are mostly about electing more moderate or less extreme candidates.”

Alaska

A measure will appear on Alaska’s ballots in November to potentially repeal ranked choice voting, established by a ballot measure in 2020 that will remain in effect for November’s election where voters will rank up to four presidential candidates in the general election, including Vice President Kamala Harris, former President Donald Trump and several third-party candidates.

Ballot Measure No. 2 would also revert the state’s primaries back to partisan primaries, allowing voters to vote in only one party’s primary election.

The measure also codifies new rules and penalties related to campaign finance. Any entity that receives more than $2,000 in a year from a donor will be required to disclose all receipts from that donor.

The state’s division of elections estimates it will cost at minimum more than $2.6 million to implement the measure if it is passed into law. These costs will include carrying out a public education campaign to inform voters about reverting to the single-choice election system and political party primaries.

“There are a couple highly publicized examples where a more centrist candidate won because of ranked choice voting,” Stewart said. “Alaska is the poster child of this.”

Stewart refers to Rep. Mary Peltola, D-Alaska, who defeated former Vice Presidential candidate and Gov. Sarah Palin in a race for the state’s at-large House seat in 2022 when Alaska first implemented ranked choice voting.

Colorado

In November, Colorado will vote on Proposition 131, a measure to adopt ranked choice voting statewide and establish all-candidate primaries. Ranked choice would be used for “certain state and federal elections.”

Boulder County, Colo., Clerk Molly Fitzpatrick oversaw the first ranked choice mayoral election in the city in 2023. The city approved it in 2020, giving her more than two years to prepare for the transition.

“It was an enormous lift. I’m very proud of what we did,” Fitzpatrick told UPI. “We delivered a great election for Boulder voters.”

The main argument against ranked choice is that it can be confusing for voters. Fitzpatrick told UPI it can be a more confusing process, increasing the need for voter outreach and education.

Fitzpatrick said she received positive feedback about how her office administered the election, particularly emphasizing voter education on the new method of voting. Yet she has reservations about implementing it statewide by 2026, as Colorado’s Proposition 131 calls for.

Fitzpatrick, who is also president of the Colorado County Clerks Association, told UPI that she worries rural counties are ill-equipped to transition to ranked choice voting so quickly.

“It’s one thing for Boulder County to do it. We’re one of the best-resourced counties in the entire state,” she said. “We put a lot of resources and manpower into it. Honestly, small counties just don’t have that.”

Fitzpatrick adds that Boulder County hired a tech company to develop software that could display how the voter rankings moved from round to round. They also needed to invest resources in outreach to prepare voters.

“The state has to really step up and create the structure to do this successfully,” she said. “When I think about that, I think about a statewide voter education campaign, developing technology that doesn’t currently exist, election official education. They have to be trained on how this impacts their processes. Then of course rulemaking.”

Linda Templin, executive director of Ranked Choice Voting for Colorado, agrees that 2026 may be too soon to implement the new election process in Colorado. While she supports ranked choice voting, she believes Proposition 131 needs more work.

“I’m glad this is a statutory measure so the legislature can make changes as needed to deliver what voters believe they would be passing,” Templin said. “Every step of what [election offices] do changes. It may take until 2028 for it to actually get implemented and for clerks to be comfortable and have everything they need for a good rollout.”

Idaho

A citizen-led initiative in Idaho called Proposition 1 will ask voters if they wish to adopt top-four primaries and ranked choice voting in general elections.

The drive to put this measure on the ballot was led by Idahoans for Open Primaries. The group delivered more than 97,000 signatures to the Idaho State Capitol in July to officially put the measure before voters.

If passed, voters will be allowed to participate in primary elections without being declared to a specific party. This will open the primary process up for independent voters, Ashley Prince, campaign manager for Idahoans for Open Primaries, said in a statement.

The Foundation for Government Accountability is one of the leading organizations to oppose the measure. In an informational packet the group submitted to the Idaho legislature, it alleges that ranked choice voting will slow down ballot counting, make the count less accurate and diminish voter confidence.

FGA also claims that ranked choice voting causes ballot exhaustion. It describes this as votes being tossed out because they were filled out incorrectly or the candidates voted for are no longer in contention.

“Ballot exhaustion leaves voters and voices uncounted — ballots are literally thrown in the trash because the RCV voting process renders their votes meaningless,” the packet reads.

The Foundation for Government Accountability did not respond to requests for comment.

Missouri

Missourians will vote on a state constitutional amendment that would pre-empt any legislation attempting to implement ranked choice voting, effectively banning it in the state.

Under the amendment, voters will continue to have a single vote for each office up for election. It will also maintain the primary process that selects a single candidate to represent a political party in the general election.

State Sen. Ben Brown sponsored the amendment.

“Ranked choice voting initiatives further erode trust and disenfranchise voters,” Brown told the elections committee and senate earlier this year during a hearing. “Under ranked choice voting, the ultimate winner of the election is often not even the candidate who is even the first choice among voters.”

The state does not use ranked choice voting currently but St. Louis conducts a similar form of voting in local non-partisan elections, stateSen. Doug Beck said during a senate meeting in April.

St. Louis passed a proposition to enact approval voting in its mayoral elections in 2021. This offshoot of ranked choice voting allows a voter to select as many candidates as they want for office. The candidate that receives the most votes wins.

Nevada

Voters in Nevada already voted in favor of open primaries and ranked choice general elections in 2022 but they must do so again for either measure to be adopted.

The state requires constitutional amendments to pass two consecutive ballot measures to be adopted.

Question 3 received more than 52% of votes in 2022, about 525,000 votes in total. If passed again in November, it will allow voters to participate in any primary election they choose, regardless of party. They will also be able to rank candidates for U.S. Congress, governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, treasurer, state controller, attorney general and the state legislature.

Unlike some states, Nevada’s proposed ranked choice system gives voters the option to rank their top-five choices.

Supporters of the measure in Nevada argued to the Ballot Question Committee that it will give voters “more voice” and “more choice.”

“Ranked choice is a simple change to our general elections that allows voters the opportunity to rank up to five candidates who best represent their positions, rather than having to choose between the ‘lesser of two evils,'” the report from the Ballot Question Committee reads.

The argument against the measure states that it will make elections more complicated and will be costly for taxpayers.

“Currently, Nevada’s voting process is straightforward: voters pick which candidate they support, and the candidate with the most votes wins. Ranked-choice voting makes casting ballots more confusing and tedious, and decreases participation in our elections,” opponents argued.

Oregon

The Oregon legislature passed an election reform bill in 2023 to implement ranked choice voting. For it to be amended into the state constitution it must be adopted by voters in the general election.

Measure 117 aims to adopt ranked choice for state and federal offices. This includes the office of the president.

The estimated financial impact to the state government for implementing Measure 117 is about $1 million between 2023 and 2025, according to the Legislative Fiscal Office. This impact will grow to about $5.6 million for 2025 to 2027. The office notes that the cost to local governments is more difficult to discern.

County clerks project that it will cost about $2.3 million to improve voting technology, train staff and test new systems. Each statewide election will cost about $1.8 million for additional printing and planning. Software and maintenance contracts are expected to cost about $400,000 per year.

Washington, D.C.

Initiative 83 is a voter initiated ballot measure to implement ranked choice voting and open primaries in the capital city of the United States.

Like Nevada, voters in Washington would be allowed to rank up to five candidates in an individual race for office. Voters may also participate in the primary election regardless of party.

As of Oct. 23, more than 24,000 drop-off ballots have been received. More than 36,000 have been received by mail. The D.C. Board of Elections began gathering ballots on Oct. 12. Early voting begins on Monday.

There were 344,356 votes cast in the 2020 presidential election in Washington.