An independent expert report on the EU’s Framework Programmes for research and innovation recommends major role for research funding and a restructuring of funding mechanisms.

By Horizon Staff

Europe needs to spend much more on research and innovation and put them at the centre of its economy if it wants to boost competitiveness, the chair of an expert group evaluating the EU’s flagship research funding programme said in an interview with Horizon Magazine.

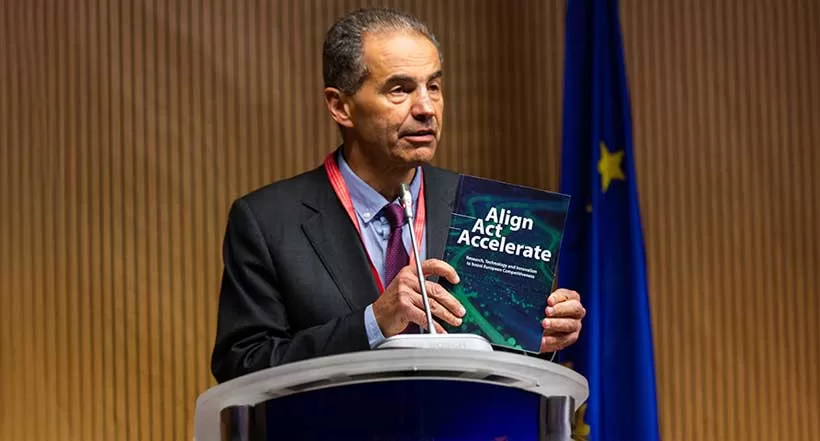

Professor Manuel Heitor, the former Portuguese minister of science, technology and higher education, presented his mid-term report on the Horizon Europe programme in Brussels on 16 October and set out priorities for its successor, which will run in 2028-2034.

Cautioning about a fast-changing world, particularly in technology, he said the EU budget for research should more than double to €220 billion in the next period, while procedures must be simplified and costs for participants reduced.

Horizon Europe, with funding of almost €100 billion during the 2021-2027 period, represents the third-biggest part of the EU budget, after cohesion policy and agriculture.

Heitor said Europe will also need to increase international scientific cooperation, particularly with researchers from China, but also with the USA, Africa and Latin America, to remain globally relevant.

He also proposed the creation of two new councils, for industrial competitiveness and societal challenges, and stressed the need to turn the brain drain of young scientists from Europe into brain gain in the next decade.

Read the interview below for more details on several issues related to research and innovation and Heitor’s recommendations for the future.

Why did you call your report ‘Align, Act, Accelerate’?

We need to align European economic, social and defence strategies in a way to boost research, technology and innovation. Act to make it promptly and boldly, to make sure that research, technology and innovation are at the centre of our economy. Accelerate the regulatory and institutional process to make sure we face the rapid landscape of technical change.

The emerging landscape of research and innovation is dramatically changing, and we therefore need to accelerate the institutional processes to fund and promote research, technology and innovation.

How do you think the context of research in Europe has evolved since the last assessment was published seven years ago? What is different now that should be taken into account for the future?

Seven years ago, we were not able to create start-ups. That has now been achieved and we should be proud. We have created more start-ups than the United States over the last five years. But, the current point is that we have not been able to scale them up and the recent data from the Commission should be a concern for all of us. Most of the start-ups that have really grown to the so-called “unicorns” or start-ups that have become companies with a market valuation above €1 billion, they have grown in the United States, not in Europe. They have grown essentially through American investment funds, and this is a wake-up call for Europe.

Second, we see from the Commission data that the biggest fraction of patents derived from fundamental research funded through the European Research Council have been valorised in the United States through large American companies and large American investment funds, and not in Europe. So something is still wrong with the scaling-up process in Europe.

The last official data from Eurostat shows that in Europe, we have been able to significantly increase the number of researchers to more than 2 million researchers in 2021, accounting for about 1% of the European labour force. The point is that we have attracted young kids and young PhDs for research and innovation, but we have not been able to improve the quality of the research jobs at the same pace.

We have increased the number of researchers, particularly young researchers, but at the same time, we are facing a very serious brain drain of young PhDs, particularly to the United States. And this does not affect just small countries in eastern or southern Europe; it affects, above all, large Central European countries like France, Italy, Spain and Poland. Therefore, we need to take it very seriously.

How has the international research scene changed?

Recent literature shows in many ways that in quite a few areas, it’s Chinese scientists that lead in science fields. We pointed out that this is a wake-up call for Europe, for a completely new way to understand international collaboration with the United States, but certainly also with China, and also with Europe’s unique capacity to collaborate with Africa and with Latin America. The way we need to understand international collaboration is completely different.

We give a clear example in our reports that despite the economic fight between the United States and China, you see that the same scientific collaboration between American and Chinese scientists has increased dramatically over the last decades. And European science, the collaboration between European and Chinese scientists, is still very, very low compared to that in America. […]

Your report includes 12 recommendations. If there was just one that you could highlight, which would it be?

We need a robust framework programme. We need a budget of at least 220 billion euros, including a radical simplification in the application process. This sentence includes three main messages: a robust framework programme; an adequate budget; and radical simplifications, with radical innovations in critical areas (global cooperation, innovation procurement, defence research).

A robust framework programme requires including a portfolio of four interrelated and interconnected “spheres of action”: competitive excellence; industrial competitiveness; societal challenge; and the European research and innovation ecosystem. […]

We have observed an increasing complexity of the process, not necessarily on the Commission side, but on the beneficiaries’ side…The application forms started introducing a number of needs to describe the social impact, economic impact, and technical people passed that to consultant firms to write.

So this dramatically increased the complexity of the programmes, which has resulted in many leading innovative companies, small and large companies, saying: ‘We don’t want to be involved in that complex issue’. This is bad, it is unacceptable. So the framework programme needs a radical simplification in order to reduce the complexity for the beneficiaries, not necessarily only for the Commission. […]

This should be a people-driven programme, user-driven, and should be more bottom-up, with a much better compromise between bottom-up and top-down research, by using less prescriptive calls.

How many of the 12 recommendations do you think could be delivered during the lifetime of the current Horizon Europe programme?

Our recommendations are clearly to be implemented in the next three years of Horizon Europe, that’s to say 2025, 2026 to 2027, to experiment with new ways to govern the programme in a way to build the next framework programme. So, for instance, the two new councils we suggest to govern industrial competitiveness and societal challenges should be created in 2025. […]

And we introduce the need to better consider the quality of the research jobs created, in parallel with the quality and impact of research results. But this needs new assessment methods, strengthening “peer review”, but using the support of new advanced technologies and systems (including AI-based), together with new tools to reduce “time to funding”.

There are several tests, particularly in private foundations throughout the world, and the Commission should test these in the coming three years to implement new assessment and funding schemes which need experimentation. We don’t know how to do them, so we need top people considering these, and testing and experimenting with new schemes.

Because again, the time to funding in the current programme and in Horizon 2020 is becoming unacceptable, almost one year. But also the time to prepare proposals is enormous. So, we need to decrease those times, making use of new tools and artificial intelligence, particularly, to speed up these processes.

What do you think would happen if the recommendations in your report aren’t followed up?

We will continue to see a decline in European competitiveness. Therefore, this set of reports, the Letta report, the Draghi report, Ursula von der Leyen’s Europe’s Choice, should be used as a wake-up call for Europe. We should be proud of the European project. But this idea should not be to do business as usual. We should also be proud of our capacity to do better. We have the capacity to do better. And this, our report, wants to be a wake-up call for ‘don’t keep doing business as usual’. […]

Over the next two to three years, we will have a strong discussion in the EU Member States and in the Council, certainly, in the Commission, and above all, in the European Parliament.

Stakeholders need to use these reports to do their advocacy. And the final decision will certainly be a very collective process. Therefore, this report, the Letta, Draghi reports, von der Leyen’s Europe’s Choice, they are instruments to be used in the advocacy.

The views of the interviewee don’t necessarily reflect those of the European Commission.This article was originally published in Horizon the EU Research and Innovation Magazine.