Until the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 last year, an Israel-China trade relationship, particularly across sectors like advanced technology, seemed to be fast growing. Now, China stances and pronouncements on the war, leave its Israel strategy in some disarray, and its broader Middle East approach about to face stark truths about the old, internecine rivalries in the region.

Over the last several years, or at least until October 7, 2023, China attempted a careful, cautious and calibrated balance between Iran and other rival powers like Saudi Arabia and even Israel. China’s policy for the Middle East, and indeed a wider West Asia, has been layered, somewhat dichotomous, and complex. It’s not one that’s easy to sustain in the long-term.

There’s one layer that is diplomatic and strategic. It’s ostensibly designed to convey through its statements and stances at the UN, and across the Middle East, and indeed across the Global South, that China has a new ideological vision for the globe, untrammeled by the US There’s another layer that’s driven by economics and the rising economic ties between China and some of the leading economic powers among the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar. Much of Beijing’s Israel strategy, too, was tied to economics.

However, in the aftermath of the attack, and the subsequent hard-hitting war that Israel has waged against Iran’s proxies like Hamas, the Hezbollah and the Houthis, Beijing’s difficult hedging game, which is as much about perception as it is about reality, leaves China in a position where it’s construed as taking sides. Beijing stances since October 7, 2023, have left it somewhat hampered as an unbiased and objective peace keeper in the ongoing conflict. Further, from Beijing’s long-term point of view, choosing sides between rival Middle East powers is the least favorable option.

THE DICHOTOMY

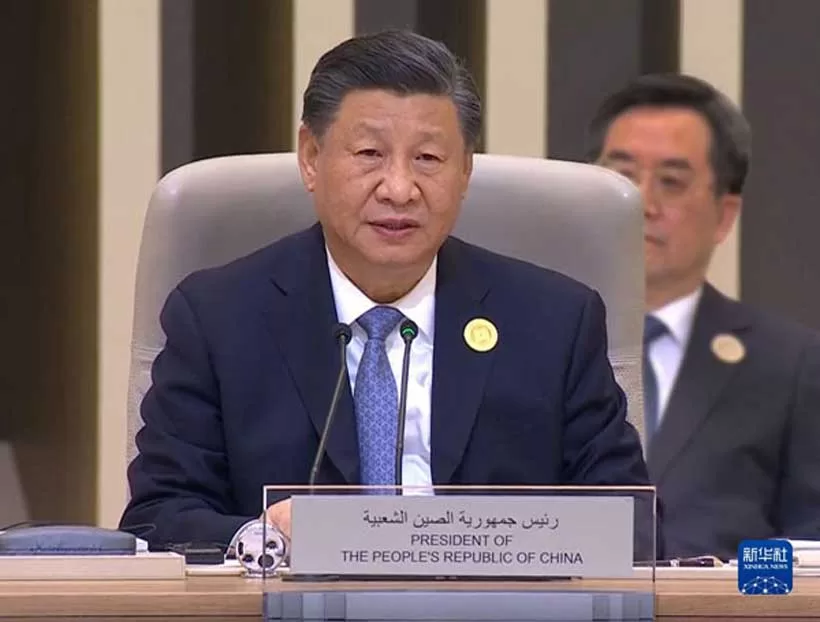

Last week, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, spoke to both Iran and Israel calling for an “immediate, complete and permanent” ceasefire in Gaza. The Chinese, pro-government online media outlet Global Times said, paraphrasing Wang, that China believes that the tensions and conflicts and turmoil in the region “serves the interests of no one”.

Though China has repeatedly articulated calls for peace, it has often chosen to criticize Israel in strong terms, without explicitly condemning Hamas’ actions. On October 12, China’s foreign minister Wang Yi in a severe chastisement of Israel’s actions in Lebanon and Gaza said that Tel Aviv had gone “beyond the scope of self-defense”. He called for the Israeli government to “cease its collective punishment of the people of Gaza”.

Earlier in March, at the United Nations, China vetoed a United States (US)-led draft for a ceasefire. The US draft stated that “an immediate and sustained ceasefire to protect civilians on all sides”, that could help facilitate “essential” aid delivery and “tied to the release of hostages” was an “imperative”. Admittedly, the US too has refused to go along with some draft texts calling for a cessation or pause in the conflict, many of them not quite allied with Israel’s interests. But Washington’s interests, and stances, in the Middle East are long established.

Beijing has gone further. It has been unwilling to work with the US and its allies to monitor the sea lanes in the Bab-el-Mandeb strait to manage the attacks on ships by Iran’s Yemen-based proxy, the Houthis, despite a naval base in close proximity at Djibouti. Instead China and Russia have reached a quiet understanding with the Houthis that their ships won’t be targeted. For the short term at least, Israel appears considerably miffed and Saudi Arabia worried.

The first layer of China’s strategy, which uses soft power effects to convey an ideological message that runs counter to perceptions about the US, is hard to deliver. It involves trying to balance complex and contrary interests in the Middle East—an Iran with a Saudi Arabia for example.

Beijing’s position is also conflicted when it comes to managing between Tehran and Riyadh. In a move designed to manage Iran’s Middle Eastern power rivals, while simultaneously ensuring that Beijing remained a player in the larger ramifications emerging across the region, China’s foreign vice-minister Deng Li also discussed the conflict with the Saudi deputy foreign minister Waleed bin Abdulkarim El-Khereiji on October 14. However, beyond the commonality of objectives that seeks to bring an end to the conflict, the regional powers like the Saudis would be aware of Beijing’s motivations and constraints.

China needs Iran as an ideological partner, alongside Russia at the current stage of a global anti-US axis. But that leaves it caught in a cleft stick. Beijing does not want to see any long-term instability in the Middle East. The region’s internecine conflicts damage its long-term economic interests and detract from the regional and global ideological stances that it’s trying to project.

THE HEFT IS ABOUT ECONOMICS

Though China did broker a peace deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia last year, and the Iranian foreign minister Abbas Aragchi did visit Riyadh and meet with the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on October 9, Riyadh will remain cautious and insecure about its own security interests arising from its proximity to the conflict.

The 2023 peace agreement is vital since it has created the opportunity for today’s dialogue. But the Saudi stance, in the current war-driven environment, draws less from any China brokered peace, and more from Riyadh’s own fears about the threat that Tehran poses to the wider Middle East, directly or indirectly through its proxies.

This strategic first layer also draws virtually nothing from China’s rising military power. Though China has a base at Djibouti, in a report in June this year, RAND authors, Howard Wang and Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, pointed out that China’s bases are more likely to focus on protecting sea lines of communication, rather than wartime utility, at least through 2030. It’s an argument that largely fits in with the role that China’s base in Djibouti has played through this Middle East conflict.

The RAND report also points out that though China’s 2020 NDU Science of Military Strategy claims “hegemonic countries are exercising control over important SLOCs that are vital to China for the strategic purpose of encircling and containing China”, there’s “neither the intent nor the capability to use overseas military bases to launch preemptive attacks or other offensive operations on US forces or interests through at least 2030.”

RAND’s argument if taken further, from the perspective of the Middle East, could mean that there’s little likelihood that China, with its preoccupations in the Taiwan Straits, the South China Sea, the East China Sea would immediately build or utilize any bases that act as peace or force multipliers in or around the region. The US therefore remains a vital security provider in the region, and the key Middle Eastern powers like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar would loathe losing their options with the Washington, particularly when it comes to Iran.

This means that any diplomatic heft that Beijing draws in the Middle East, as a peace keeper, will have to be drawn by the complex task of carefully balancing between Tehran and Riyadh, while quietly building economic heft across the region. This, inevitably, ties into the second layer of China’s strategy—economic relationships and the ability to draw from economic heft—particularly when it comes to a relationship with key Middle Eastern states like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates or Qatar, or, for that matter, even Iran.

IRAN IS A STRATEGIC WEAKNESS

China is moving quickly to buttress its economic ties. When it comes to Iran, however, the issue is more a classic case of economic dependence than any mutually advantageous economic relationship. Economic dependencies, if artfully created, can be advantageous, growing economies are vital to build markets and drive capital. The other countries in the region, like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, are more about interdependence, driving mutually beneficial capital flows, and markets.

The World Bank, in its Spring 2024 Iran Economic Monitor said that the country’s oil production surged by 17.2 percent in 2023-24 on a year-on-year basis, “the highest level since the re-imposition of US sanctions in 2018”. However, the World Bank added: “Despite higher oil export volumes, oil revenues in 2023-24 are estimated to have fallen significantly short, meeting half of their budget target, based on an assumed 1.5 million barrels per day of oil exports at US$85 per barrel.” Nearly 90 percent of this oil went to China according to the analyst firm Kpler. The Iranian financial year, in line with its calendar year begins on March 21 and ends on March 20 of the following year.

The World Bank report also pointed out that Iran faced revenue shortfalls in 2023-24, with “only an estimated 72.6 percent of planned revenues” actually materializing, highlighting the significance of oil revenues to the economy. However, Iran’s oil revenues issue weighs wholly in China’s favor since Iran is paid in yuan, which leaves Iran with few options other than maximizing its imports from China or parking the monies in a Chinse bank. China’s yuan is not freely tradeable globally and is not yet a universally accepted store of value or unit of account. There’s little concrete data available on Iran’s trade with China.

China committed a $400 billion investment in Iran through a trade and security partnership agreement signed in 2021, but little advantageous investment has accrued. The Rhodium Group estimates that Iran has seen just $76.42million in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from China between 2021 and this year. In contrast, Israel has obtained $549.06 million from China as FDI over the same period.

Wang Yi’s October 14 conversation with Araghchi has crucially been about China-Iran ties. Araghchi has reportedly pointed to the value that Iran places on China’s influence in international affairs and Tehran’s willingness to “strengthen communication and coordination with China to cool down the situation through diplomatic means”.

On October 16, the Tehran Times carried an op-ed by a Chinese scholar, Jin Liangxiang, that emphasized how “China was strongly committed to its Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) with Iran, and China and Iran will see stronger cooperation”. The op-ed went on to add that China and Iran were natural strategic partners and, in keeping with both Beijing and Tehran’s ideological stance, argued: “Both China and Iran are victims of US bullying and sanctions. Despite sanctions, the two have enhanced economic relations with each other, though higher expectations are always there.” However, while emphasizing rhetorically how “the security of the world should not be divided, and countries should work together to deal with the shared security,” the op-ed gave little concrete data on how the CSP had actually been implemented on the ground.

Iran’s economic dependence on China, and the weakness of the Iranian economy, gives Beijing advantages when it needs Tehran’s acquiescence in it’s anti-US game, but offers little two-way economic advantage, or broader diplomatic weight beyond Russia and a few other nation-states. That can come only from the other growing economic countries of the Middle East.

THE GCC AND INTERDEPENDENCE

With Israeli ties in something of a disarray, China’s need to maintain its relationships with the Saudis, the Emiratis and the Qataris becomes all the more crucial. China’s investments into countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar stand in very sharp contrast to the limited investment in Iran. China’s investment in Saudi Arabia across construction initiatives alone amounted to $18.43 billion during the period 2021-24, according to the American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) China Global Investment Tracker. The Rhodium Group estimates Chinese FDI into Saudi Arabia at $738.41 million for the same period.

For the 2021-24 period, Chinese FDI into the UAE was estimated by the Rhodium Group at $2.5 billion, while AEI estimates indicate $3.76 billion worth of investments in construction alone. AEI’s estimates for Qatar, for the 2021-24 period, are $2.02 billion, while the Rhodium Group estimates $56.91 million in FDI from China.

Trade and investment related activity between the GCC countries is rising quickly. There have been numerous visits between the trade ministers on both sides, besides participation in trade fairs, resulting in several signed agreements of late.

In September, Saudi Aramco signed agreements with China’s Rongsheng Petrochemicals and the Hengli Group for joint ventures and investments across both Saudi Arabia and China. An Aramco press release stated: “The agreements reinforce Aramco’s ongoing contribution to China’s long-term energy security and development, support China’s participation in Saudi Arabia’s economic growth, and foster collaboration in new technology development. They include preliminary documentation relating to a Development Framework Agreement with Rongsheng Petrochemical Co. Ltd. and a Strategic Cooperation Agreement with Hengli Group Co. Ltd.”

Saudi Aramco also signed a five-year deal with China National Building Material Group to set up manufacturing facilities for hydrogen storage tanks, lower-carbon building materials, energy storage solutions, and wind turbine blades in Saudi Arabia. Saudi funds have been given the go-ahead for exchange-traded funds (ETF) that track Hong Kong–listed equities. A Hong Kong fund launched an ETF in November 2023 for Saudi stocks raising over $1 billion.

As EU investors relook at their investments in China, GCC capital is becoming all the more important for Beijing. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, quite flush with funds, are investing in China, highlighting the interdependence. Bloomberg indicates that acquisitions by GCC’s sovereign wealth funds in China rose to $2.3 billion in 2023, from just $100 million in 2022. Bloomberg also indicates that deal volume in the first nine months of 2024 was around $9 billion.

This August, UAE’s sovereign wealth fund (SWF) Mubadala Investment Company said it acquired a 100 percent stake in the Chinese unit of the Belgian company UCB, alongside the CBC Group. In September, the AD Ports Group, a subsidiary of ADQ, a UAE SWF, announced it had awarded a contract worth $114.35 million to China’s Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Co., for a supply of cranes for AD’s terminals in the Republic of the Congo and Angola. On September 19, Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Airways and SF Airlines, a subsidiary of China’s largest delivery and logistics company, announced a joint venture representing “a full strategic alignment between Etihad Cargo and SF Airlines, combining their strengths to offer a unified, comprehensive logistics solution to customers worldwide”. UAE’s Orbital Space inked an agreement with China’s Deep Space Exploration Lab, targeted at providing support for China’s International Lunar Research Station.

Qatar Energy inked an agreement with the China State Shipbuilding Corporation for six new LNG vessels for delivery 2028 and 2031, which is in addition to a pending delivery of another 18 LNG vessels. China’s UISEE signed a deal in mid-September for research-and-development at the Qatar Science & Technology Park.

The oil and natural gas-driven interdependence alone is highly significant. In his Congressional Testimony in April this year Jon B. Alterman, director of the Middle East Program at CSIS testified that since 1993, “about half China’s oil has come from the Middle East.” In a report in June this year the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, analyst Alexandre Kateb pointed out: “Asia as a whole now absorbs over 70 percent of total GCC oil and gas exports, with China alone accounting for 20 percent.” Other analysts at the Columbia-SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy, Erica Downs, Robin Mills and & Shangyou Nie, in July, highlighted the significance of China’s recent natural gas deals with Qatar pointing out: “In 2022, Qatar was China’s second-largest LNG supplier, delivering 24.8 billion cubic meters (bcm) or 18 million tons, which accounted for 26.6 percent of China’s LNG imports and 16 percent of China’s total natural gas (pipeline and LNG) imports. China was Qatar’s largest LNG buyer, accounting for 21.7 percent of Qatar’s exports.”

From China’s perspective, the GCC countries are both a source of funds and markets for Chinese goods. Reports indicate that Chinese conglomerates like Alibaba, Tencent, and Meituan are looking at Saudi Arabia as both investment sources and a potential market. From a GCC perspective, China offers a path to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and a new market for investment.

China is a critical partner since it’s a dominant player across vital technologies and supply chains, particularly batteries, lithium, critical minerals and wind power, all important for the growth of the GCC countries. China is also a conduit into Asia’s fast-growing markets, and a source of, and a destination for, equity and investment capital.

However, despite the growing attempts to further trade denominated in yuan and local currencies, the GCC countries remain conscious of the yuan’s limitations as a global currency. The GCC is also wary of US pressure on Chinese investment. The US has also placed restrictions on the sale of Nvidia chip to the Gulf states, lest the chips end up in China. The UAE technology firm G42 was compelled to divest its Chinese stake which included an estimated $100 million stake in ByteDance.

Beijing, of course, cannot be expected to openly side with the US role in conflict between Israel and Iran’s proxies. But it’s dance in the Middle East leaves it vulnerable on several counts, particularly when it comes to the old Iran-Saudi Arabia differences. If the war does worsen and widen, and push comes to shove, China may well find it’s faced with a difficult choice between Middle Eastern rivals.