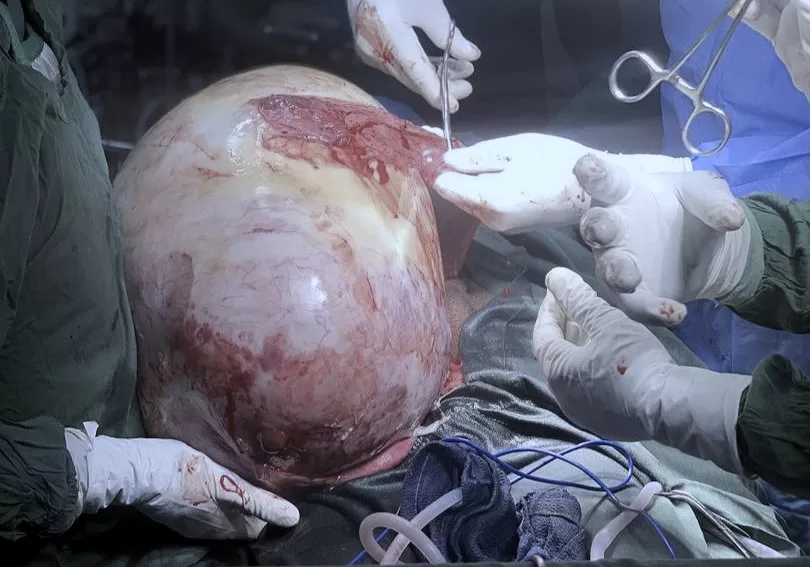

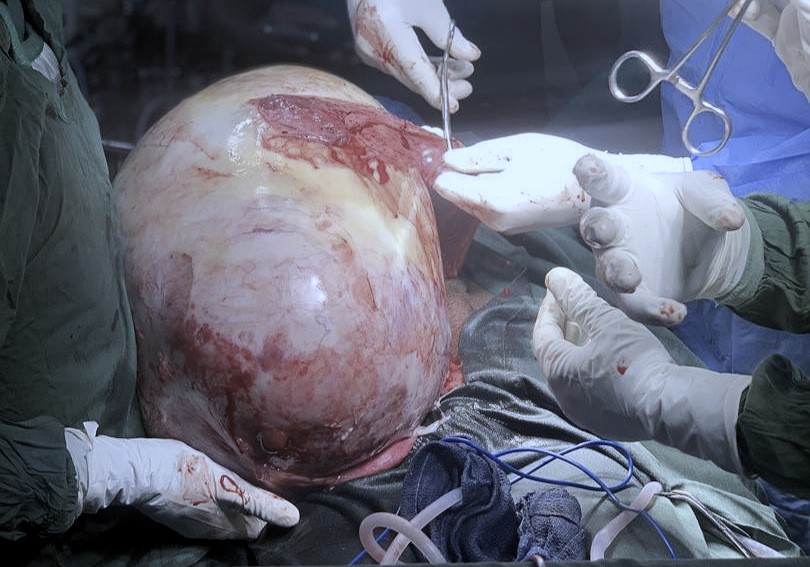

Image discretion warning: This story contains descriptions of a medical condition and includes an image of a tumour removed during surgery, which may disturb some readers.

When Aisha Abdulazeez Gidado’s stomach slowly started to increase in size, she and the people around her dismissed it as regular bloating despite her small stature. But when it persisted, her mother, Fawziyya, who has a background in microbiology, started to get worried and suggested that she go to the doctor for a scan.

Her visit didn’t yield the expected results; to make matters worse, she wasn’t showing any other symptoms. “Most of the doctors did not take us seriously,” the 19-year-old said. “Even though they hadn’t figured out what it was, they still suggested surgery. My father said no since they didn’t know what they were looking for.”

It took a few years before she started experiencing other symptoms, such as headaches, weakness and stomach pain. It was a lot to deal with, so much that sometimes, she was convinced she was dying.

In November 2019, she started gaining weight, but her stomach was not proportionate to her increasing size. That began to make her mother anxious.

“When I first touched her stomach, it felt very hard, and I immediately took her to Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Yola [in northeastern Nigeria]. During that time, the resident doctors were on strike. I suggested a scan, but we couldn’t see anything in the stomach, and it looked very hazy,” her mother, Fawziyya, explained.

The doctor said he couldn’t figure out what it was and suggested a test to find out what seemed to be pooling in her stomach. He suspected it was either urine or water. He tried using a syringe to draw a sample, but what he saw was very clear water. He then ran hepatitis B and C, liver function and many other tests to rule out other possibilities before referring them to his consulting office in Wuro Hausa, Yola.

The only result that came out positive was the H. pylori test—a type of bacteria that primarily infects the stomach, leading to gastritis and ulcers. She was prescribed antibiotics, omeprazole and furosemide to help bring out any excess fluid built up in her stomach. It looked like it was reducing, but then it started getting worse. The doctor suspected that it might be a gynaecology case and referred them to a specialist, who asked her a few questions and suggested a pregnancy test.

Aisha was terrified by his question, but she answered honestly.

Fawziyya was worried and confused but knew she needed to do what was necessary to ensure that her daughter got the help she needed. “I didn’t know how to tell her father when they suggested a pregnancy test, so we got a pregnancy strip test, ran it at home, and it came out negative. There was a lot of tension and anxiety. I didn’t even tell her it was a pregnancy test, so she doesn’t panic.”

After that, they kept returning to the hospital, but the strike at FMC Yola in 2020 lasted for about five months, and with the COVID-19 pandemic, things were not going as smoothly as they had hoped. This led them to try traditional and natural alternatives like honey, black seed oil, and moringa.

For two years, Aisha didn’t experience any pain, but there was a time when her urine had an oily-like substance.

When FMC opened, they were referred to a doctor. The doctor asked them to do a lipid test, but everything else appeared normal. He told them to continue using furosemide, but her mother started noticing that even though her stomach didn’t seem to be reducing, she had started losing a lot of weight no matter how much she ate. Her mother suggested they stop the drug for a while and see what happens.

They then went to KEDI Healthcare, a Chinese health and wellness company with branches in over 40 countries. The doctor there identified a cystic mass in her stomach and suggested the inflammation might be linked to her liver. He prescribed medication, including antibiotics and detoxifying drugs, which initially appeared to help.

Her experience mirrors a common challenge faced by many women in healthcare. Gender bias and assumptions about women’s pain tolerance or emotional responses often lead to their symptoms being downplayed or misdiagnosed. In Nigeria, this is further exacerbated by systemic issues, such as the lack of diagnostic tools, overburdened hospitals, and poor continuity of patient care, resulting in long-term or even fatal consequences.

The social and financial impact

When it was time for her to start tertiary education in 2020, there were suggestions by relatives that she should wait till she got better. Still, her parents decided it was better for her to continue her education—hoping a solution would come along the way.

Her mother always encouraged her to live because she believed falling sick was not the end of the world. Even though going outside and going to school drew a lot of questions and attention to her, her parents didn’t want to risk her getting depressed while stuck at home in her youth as her mates and friends moved on with their lives.

She is currently studying at the Federal College of Education, Yola, in Adamawa state. Coping with school was a challenge as people often asked if she was pregnant, but her determination and support from her friends helped.

The family kept using the KEDI treatment for about a year. “Each treatment costs ₦70,000 to ₦100,000,” Fawziyya explained. “We couldn’t afford it, but we had to forego other things as her health was a priority for the family. There were a few times we had to pay in instalments.”

Part of her treatment included dietary changes. At a point, the doctor said he didn’t know which drugs to recommend again as they had exhausted their options.

They went to a new private hospital in Yola and repeated the same tests. The hospital referred them to FMC again. This time around, the federal hospital made them run a CT scan, and that was when they started seeing signs of cancer.

Even though ovarian cancer ranks eighth as both the most common form of cancer among women and the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, women and girls still struggle to get a proper diagnosis.

Before they got a solution, her parents monitored her diet and cut out things like sugar. They were referred to a woman selling traditional medicine in Delta state who gave them drugs for fibroids and cysts. Sometimes, it looked like she was getting better, but only briefly.

“We saw a doctor who told us that the best solution was to open her up to figure out what the exact problem is. And they would remove all her ovaries. Our anxiety got heightened, and many people around us recommended we shouldn’t go ahead with the surgery.”

They kept looking for other alternatives. Her mother believed they may have considered it if he had explained it differently.

“We haven’t kept a record of the finances because we spent so much money over the years,” Fawziyya told HumAngle.

“We went to try an Islamic chemist in Kaduna, and he said he had never seen anything like this, especially on a young girl. So, he suspected that it could be a spiritual attack from djinns. He asked me a few questions about whether I had weird dreams or isolated myself. I said I do sometimes,” Aisha recalled. He then gave her some drugs, which she used until this year.

During one of her exams in school, Aisha collapsed when the lecturer in charge was reassigning seats and asked her to move.

“Immediately, I sat on the assigned seat, and I started feeling dizzy. Another lecturer noticed and asked what was wrong. I asked if I could go to the toilet, but I collapsed when I tried to get up. They called my sister, and I was taken to the clinic. The doctor then said I needed a blood transfusion.”

A spark of hope

Aisha’s family were later referred to a gynaecologist who is considered an expert in cancer treatment.

The doctor, Maisaratu Sa’idu Ahmad, picked an interest in the case and fixed an appointment. The hospital was scheduled to join a labour union strike by 2 p.m. that day, so the doctor told them to get admitted quickly. Aisha’s body was starting to break down.

“We went to the side of the clinic designated for gynae emergencies. I took along all the test results we ever ran. I kept encouraging her to be strong and keep praying. The doctor was very kind and thorough. The first day she saw her, she even gave her a hug. Because we were seeing Aisha often, we didn’t even realise how bad she looked,” Fawziyya explained.

The admission took a lot of money; they ran about 13 tests and had to take one sample to Abuja to get it tested. The hospital also told them to buy compression socks and four pints of blood for the scheduled surgery.

“People kept dying in the cancer ward she was in, and that triggered her anxiety,” said Fawziyya. Sometimes, she caught Aisha crying even though she tried to hide it.

After the surgery, which lasted about 40 minutes, Aisha was later taken to the ICU. To everyone’s horror, the tumour that was removed weighed about 16kg.

Fawziyya recalls the experience as if it were yesterday.

“The doctor suggested that we talk to her as it would help. There were times when she seemed to open her eyes, and it was after I left that place that I broke down for the first time. People came and tried to get me to stop crying, but I told them to let me cry. They didn’t know how many years I had been holding on.”

After the surgery, there was a bit of bloating, but then she started to get better. She was discharged after ten days and given frequent appointments. But when the doctor saw her again, she said she would have to be readmitted because of her worrisome appearance. They recommended a multivitamin that helped with her appetite. Eventually, she started to look like her usual self.

A test on the removed tumour showed that it was cancerous. The doctor had already prepared them for the possibility of a chemo treatment. Even though she was not a hundred per cent certain about the condition before the surgery, the way she explained to them lessened the family’s anxiety and made them trust her judgement.

Fortunately, the chemotherapy did not take too much of a toll on Aisha’s body. The hospital said they saw different kinds of cancers in the growth removed from her stomach. So, they invited a professor from the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital who examined it and told them it was a Yolk sac tumour.

Dr Maisaratu said, based on her research, the cancer was in stage 3. The chemo was based on her weight, so they didn’t spend as much as they expected.

Among all those experiences, what stood out to Aisha and her parents was the support and kindness they got. “We got so much help from family and friends. I am grateful for the support I got. I didn’t even realise how much community I had till this happened.”

Fawziyya even once received financial help from a security man at the hospital during the surgery because she left her bag in the room. He gave her the ₦100 she needed to get hot water during an emergency.

Aisha feels stronger and is already back in school. She was even able to make it to her second-semester exams.

“I hope to recover soon and get a good result at school so my parents would be proud. I also hope that the people who struggle with the same condition will have people who will look out for them.”