Camilo Acosta couldn’t imagine finding the kind of success he’s had as a tech entrepreneur anywhere besides San Francisco.

Acosta moved to San Francisco from Washington, D.C., 13 years ago and never looked back. He’s founded two start-ups here, including one that was acquired by Meta in 2020, and he runs a $30-million fund that invests in early-stage artificial intelligence companies. When it comes to the tech industry, he said, the City by the Bay is “the center of the universe.”

“This is where you see the future unfold, sometimes a decade before anyone else sees it,” Acosta said, sitting at a café across from Dolores Park, with its lush green lawn and stunning view of downtown.

But that bliss applies to his work life. Actually living in San Francisco, he said, doesn’t always feel so magical.

Acosta said he’s grown disillusioned with the property crime and the ways in which the twin crises of addiction and homelessness spill out into the streets. His South of Market office has been broken into and robbed of laptops. Another time, a homeless man wandered into the building in the midst of a manic episode. Both times, Acosta said, police offered little help.

Many people he knows have fled to Marin County, the South Bay or somewhere outside California, where they can work remotely for companies based in San Francisco without having to deal with the homeless encampments, sky-high housing costs and a political system often accused of prioritizing progressive ideology over practical results.

Acosta has no plans to join the exodus. Instead, he’s focused on the 2024 mayoral election, when he’ll get the chance to cast his vote for Daniel Lurie, a nonprofit executive and heir to the Levi Strauss fortune who is running for mayor against four City Hall veterans, including incumbent Mayor London Breed.

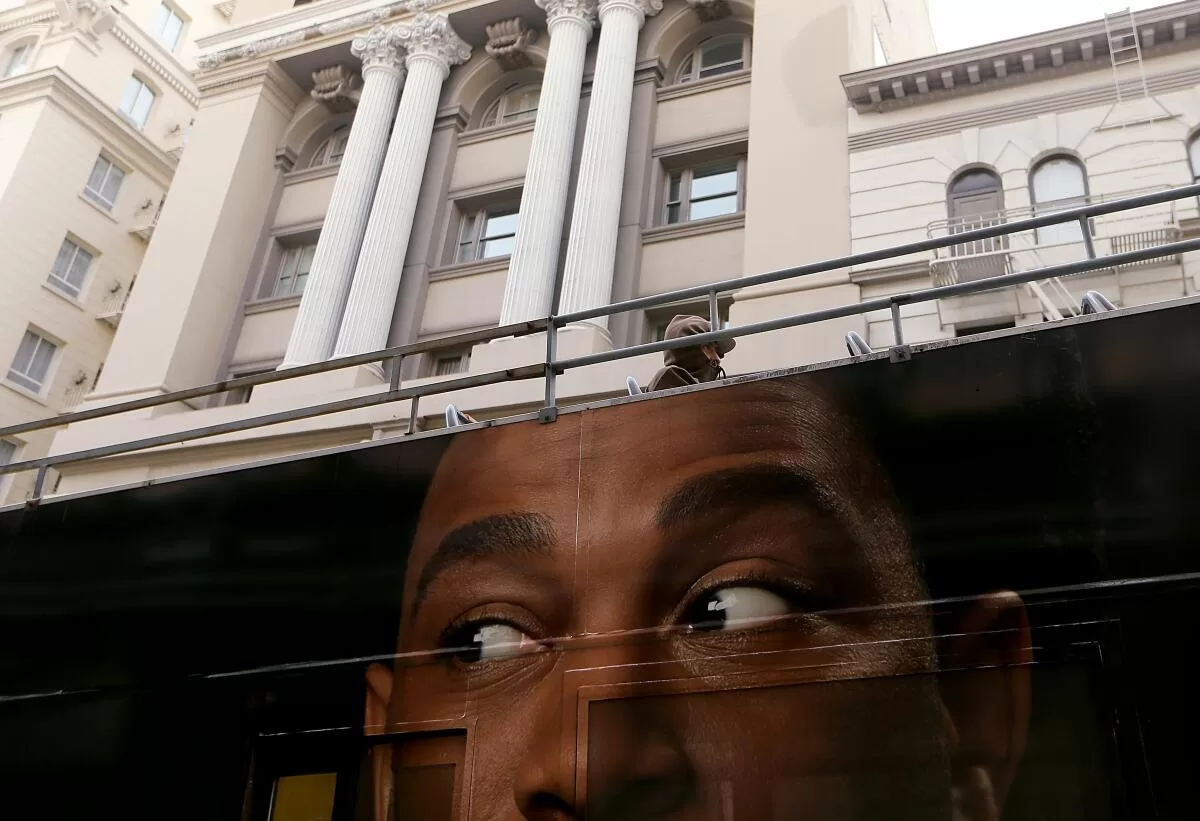

Nearly two decades after tech leaders put down business roots in San Francisco, its leaders are stepping up to assert more influence in how the city runs.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

In Lurie, Acosta sees a chance to infuse more centrist politics in this famously liberal city — a course correction he sees as crucial for San Francisco to shake off the economic and social malaise that took root before the COVID crisis and worsened with pandemic-related shutdowns. He’s donated $500 to Lurie’s campaign and coordinated meet-and-greets with his friends and colleagues.

“When I look at the slate of candidates, I see everyone else except Daniel having worked in city politics for the last 10-plus years. So they helped create this mess,” Acosta said.

This year’s mayoral race is considered one of the most consequential in decades. The candidate who prevails in November will have to deal with a list of stubborn problems — the affordable housing shortage, a lagging post-pandemic economic recovery, homeless numbers that far exceed shelter capacity — all while ushering in the era of artificial intelligence.

And the tech industry is paying attention.

Wealthy tech executives, many of their employees and the venture capitalists funding their companies have poured millions of dollars into this year’s race, marking a notable shift in their ambitions for shaping local politics. Starting nearly two decades ago, San Francisco lured major tech firms out of Silicon Valley with financial incentives and the promise of a more vibrant city life for its millennial workers.

Now that the industry has put down roots, its leaders are stepping up to assert more influence in how the city runs.

San Francisco Mayor London Breed discusses the challenges of leading one of California’s most famous and influential cities during a community panel in June 2024.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

The money has overwhelmingly benefited the candidates who have emerged as front-runners: Lurie, Breed and Mark Farrell, a venture capitalist and former member of San Francisco’s powerful Board of Supervisors who served as interim mayor for six months in 2018. All three are moderate Democrats and have campaigned on issues such as dismantling tent encampments, bolstering police powers and revitalizing downtown — some of the tech industry’s top priorities.

As the incumbent, Breed has worked to ward off the perception that she bears responsibility for the city’s ills. Her supporters note that during her first term, she has regularly sparred with the progressive majority on the Board of Supervisors, while also supporting incentives to make business feel welcomed. Last year, she declared San Francisco the “AI capital of the world.” In recent months, she has become a high-profile voice in California’s effort to get tougher on homeless people who refuse shelter, and to enact harsher punishments for retail crime.

Farrell’s appeal is rooted in his experience as a venture capitalist — one who also is familiar with navigating City Hall. He has disparaged Breed’s post-pandemic leadership, and has pledged to turn the economy around, get tough on crime and crack down on open drug markets.

Meanwhile, Lurie’s experience running a nonprofit that funds efforts to fight poverty and addiction — and his self-proclaimed status as a political “outsider” — appeal to people fed up with the status quo. And his elite family background has afforded him access to many of San Francisco’s most influential residents.

In his bid for San Francisco mayor, Mark Farrell’s appeal for the tech sector is rooted in his experience as a venture capitalist who is familiar with navigating City Hall as a former supervisor and interim mayor.

(Jeff Chiu / Associated Press)

The amount of tech money flowing to the three candidates is staggering by San Francisco standards. And while candidates with the most money don’t always win, donations fund the ads and events that get their names and platforms before voters.

Among the standout donations:

Chris Larsen, co-founder of the crypto company Ripple and other start-ups, has donated $600,000 to an independent committee backing Breed. Tony Xu, chief executive and co-founder of DoorDash, has given $100,000.

The committee has reported more than $2.5 million in contributions, and Breed’s campaign has tallied another $2.2 million. The figures include about $1 million in public financing, funding San Francisco provides candidates for top local offices who receive a demonstrated level of community support as a way of leveling the playing field.

Kamran Moghtaderi, an investment advisor at hedge fund manager Eversept, has given $250,000 to an independent expenditure committee supporting Farrell. The committee has received hundreds of thousands more from donors in private equity and venture capital, along with $500,000 from real estate investor Thomas Coates, and $450,000 from billionaire William Oberndorf, two men who have previously given to GOP candidates.

A separate committee Farrell set up in support of a ballot measure to reduce the high number of government commissions and increase mayoral powers in San Francisco reported receiving $500,000 from Michael Moritz, the tech billionaire and partner of Sequoia Capital.

In total, the independent expenditure committee supporting Farrell has received more than $2.2 million, and his campaign has reported another $1.8 million in donations and public financing. The ballot measure committee has reported more than $2.3 million in funding.

Jan Koum, a co-founder and retired chief executive of WhatsApp, has contributed $500,000 to a committee supporting Lurie. Ironwood Capital Management Chief Executive Jonathan Gans gave $300,000. Oleg Nodelman, founder of the biotech investment advisory firm EcoR1, has put in $250,000. Dozens more investors and tech workers have flooded the committee with donations.

In addition to the tech contributions, Lurie has poured more than $7 million of his personal fortune into his campaign, which has raised a total of $8 million. His mother, Miriam Haas, has given the independent expenditure committee $1 million, a hefty chunk of the $6.3 million the committee has raised.

“I think what you’re watching in politics is a realization that San Francisco is here to stay. It is going to be the tech hub of the world for the foreseeable future,” says Reinvent Futures founder Peter Leyden.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Political pundits see the money as a sign that the tech industry is finally stepping into the role of influential donor class after years of political apathy, especially as San Francisco forges its post-pandemic recovery.

“San Francisco is going to rebound. It’s already rebounding,” said Russell Hancock, president and chief executive of the think-tank Joint Venture Silicon Valley. “Most of the sector is committed to San Francisco, and they want to be a part of the solution.”

For decades, high-society families such as the Gettys, Pritzkers, Fishers, Swigs and Buells — who made their money in oil, hotels, real estate and retail — have shaped San Francisco politics, using their wealth to launch political stars such as Vice President Kamala Harris and Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Tech was viewed as that Silicon Valley business farther south on the peninsula, Hancock said. That started changing around 2008, when younger tech workers pressed to trade suburban living in Mountain View and Palo Alto for a more urban environment; and their bosses, lured by tax incentives, started relocating whole companies to San Francisco’s downtown and South of Market districts.

“It used to be that all of us down in Silicon Valley, people thought of San Francisco as an old-fashioned town, not a technology town,” Hancock said. “That changed significantly in the early 2000s, when San Francisco became a major epicenter for a whole bunch of things.”

The start-up founders of 20 years ago have since bought homes, started families and leased office space for thousands of workers. And with the rise of AI stirring terrific optimism about tech’s next chapter, some industry leaders have decided it’s time to get involved in local politics and help mold the city going forward, said Peter Leyden, a former managing editor of Wired magazine and founder of Reinvent Futures, a company that brings together top leaders in artificial intelligence.

“I think what you’re watching in politics is a realization that San Francisco is here to stay. It is going to be the tech hub of the world for the foreseeable future,” Leyden said. And “if we’re going to be here, and if this is the world we’re living in, let’s remake it in a way that works.”

For Larsen, co-founder of Ripple, the election feels personal.

Larsen was born and raised in San Francisco and went to college at San Francisco State University. His kids were born at the same hospital that he was.

For a long time, he said, the general sense in the tech industry was that San Francisco is a beautiful city, with great restaurants and ample opportunity to make lots of money; yet when it came to politics, nobody wanted “to get in all that muck.”

That changed, he said, when local governance took a sharp turn toward a “very far left, sort of performative sort of politics, rather than looking at outcomes.”

The attitude shift started during the pandemic, when offices, schools and restaurants shut down and many tech companies instituted remote work policies. The downtown office vacancy rate rose to more than 30%, and the service economy collapsed. Meanwhile, auto thefts, break-ins and homelessness surged with a seemingly muted police response.

“I think it got to a point where, OK, enough is enough,” Larsen said. “You can yell at us all you want, because a lot on the far left, they are intolerant to business and tech and all that. I don’t care, and I don’t think a lot of other people care anymore. We gotta step in here. And it’s working.”

Larsen is backing Breed. He likes that she pushes back on the more progressive voices in city and county governance, and that she’s taken efforts to bolster police powers and lower crime rates.

The pandemic helped spawn a cohort of advocacy groups backed by tech billionaires that have pushed to replace the city’s most liberal officials with more moderate figures.

In February 2022, the groups helped drive the successful recall of three school board members who prioritized renaming city schools that honored historical figures they deemed nefarious, rather than reopening classrooms. Four months later, voters recalled progressive Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin, concerned that his efforts to reform the criminal justice system made him too lenient.

“They began by removing people that they saw as really big obstacles to the greatness of San Francisco,” said Keally McBride, a politics professor at the University of San Francisco.

Encouraged by the recalls, and with money to spend, McBride said, industry leaders turned their eyes to the 2024 mayor’s race.

The campaign spending has raised concerns among residents skeptical of the tech industry’s influence. The influx of tech workers drove up housings costs and dramatically reshaped the feel of downtown. And their remote work policies, combined with a post-pandemic flight, has gutted the downtown core and fueled the office vacancy rates.

Even today, 75% of Bay Area respondents to a recent quality-of-life survey conducted by Joint Venture Silicon Valley in collaboration with the Bay Area News Group said they believe Silicon Valley’s top tech companies “have too much power and influence.” Sixty-nine percent said tech companies have “lost their moral compass.”

“My opponents are mostly supported by billionaires,” Supervisor Aaron Peskin says of San Francisco’s mayoral race. “And presumably that is who they will fight for.”

(Jeff Chiu / Associated Press)

Aaron Peskin, the Board of Supervisors president and the only candidate running on an old-school progressive agenda, has raised $1.5 million in contributions and public financing, far less than the front-runners. His largest individual donation is $1,000, according to the city’s campaign finance dashboard.

Peskin said his campaign more accurately reflects the voices of working-class residents — the teachers, nurses and artists who can’t afford to live in San Francisco anymore.

“And that is exactly who I will fight for,” he said at a recent mayoral debate. “My opponents are mostly supported by billionaires. And presumably that is who they will fight for.”

Supervisor Ahsha Safaí similarly is drawing support largely from small-dollar donors. He has raised a little more than $1 million.

“San Francisco is not for sale,” Safaí said at another debate. Turning to Lurie, he added: “Just for point of reference, my mother gave $150 to my campaign.”