The bustling atmosphere in Dalori, Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, hides the harsh reality of life in the community as many groups gather in circles to share tales of resilience.

Dalori is one of the communities targeted by many attacks from Boko Haram, including suicide bombers in the past. The worst of these attacks occurred in January 2016, when 86 people were killed and 62 others injured.

For Gambo Bulama, a 33-year-old pregnant mother of five who resettled in the community from the Muna El-Badawy Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) camp three months ago, Dalori represents a fragile haven. While she often visits the hospital provided by Save the Children—a global organisation committed to protecting children from harm—for free antenatal care, she told HumAngle that the healthcare facility lacks necessary drugs for patients.

According to Gambo, the economic hardship occasioned by the removal of fuel subsidies and the continuous devaluation of the naira has left her family struggling in their new environment. Though her husband is involved in farming, his income barely covers their needs as food prices skyrocket.

“The rise in food prices affects everyone here. How can someone like me afford a bowl of maize grit for 2,500 naira? It’s overwhelming,” she said. However, her spirit remains unbroken as she dreams of starting a small business to sustain the family.

“I know we are still recovering, but I want to improve my situation. If I could get some funds, I’d love to start a small business, maybe sell traditional dried soup leaves and other food items in small portions.”

HumAngle also learnt that the resettled displaced persons face a pressing need for quality education. Munye Ali, a 23-year-old, said the community lacks good schools for proper Western education.

“It’s been three months since we resettled here, and many young people have had to halt their education,” Munye said. “When I was in Muna, there were interventions as teachers would come to the IDP camp to make sure children went to school. Also, non-governmental organisations provided school materials. If the same energy is put into Dalori, many children would be in school.”

Since he can no longer pursue higher education, he keeps busy working on nearby farms.

“I do what I can to save money and improve my livelihood,” he added, calling on the state’s government to provide interventions for people like him and make Dalori schools functional.

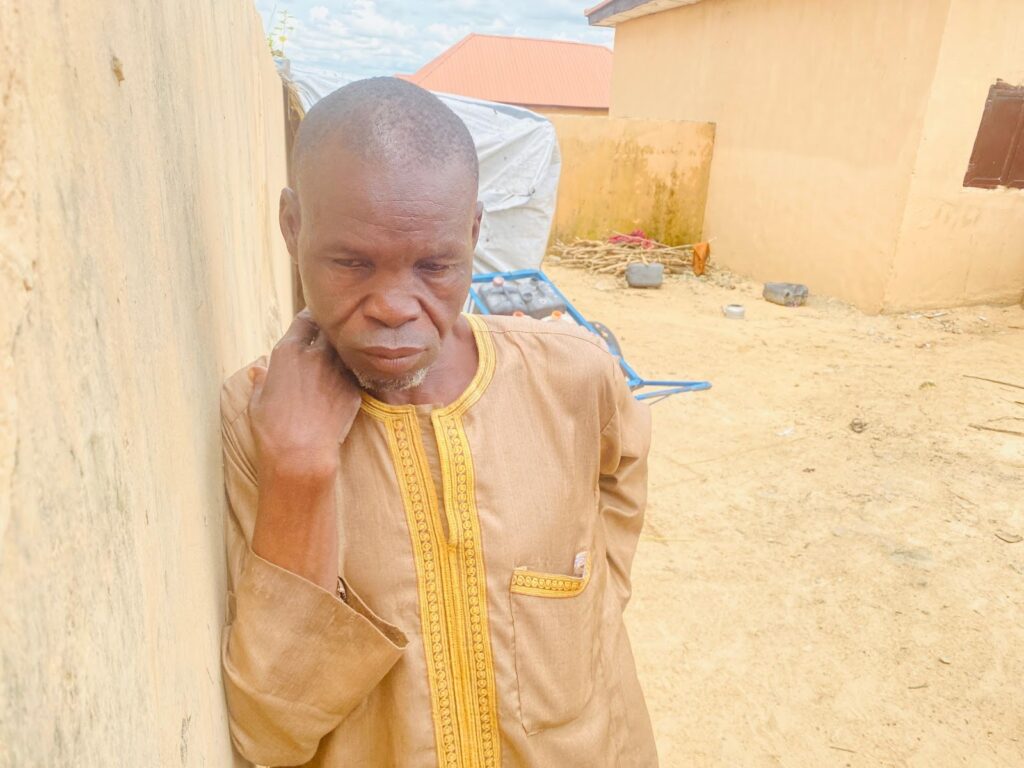

At 50, Kaka Ali Fannami sits with his hands tracing the outlines of his weathered walking stick, his eyes clouded by a persistent visual impairment that no treatment has been able to cure. He has knocked on every door for a remedy, yet his world remains blurred.

While he’s grateful for the shelter and the safety Dalori offers, Kaka pleaded with authorities to provide necessary healthcare facilities and drugs to the community to address the health challenges of aged residents like him.

“We were told they’d come back to check on us, but we haven’t seen them,” he told HumAngle. “The food and cash we received are long gone.”

Falmata Kolo, another resident who recently resettled in Dalori, shoulders the added burden of caring for a child with a disability. She collects vegetables from the forest to make ends meet, drying and selling them. Yet, the income isn’t enough to cover her family’s daily needs.

“My three children used to attend school when we were in Muna IDP, but that has stopped since we moved here,” Falmata lamented. She, however, called on “the government to help us, especially in providing funds to boost our businesses.”

In June, the Borno State government began resettling internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Muna to nine locations across the state, including housing estates in the Dalori community. This move is part of a broader plan to permanently close all IDP camps within Maiduguri, the state capital. While the government claimed to have allocated ₦954.7 million for the resettlement and support of IDPs, many resettled residents continue to struggle with hardship.

Dalori, in Borno State, Nigeria, is a community marked by resilience and struggle due to past Boko Haram attacks.

Residents, such as Gambo Bulama, face economic hardships from rising food prices and limited healthcare resources despite access to free antenatal services through Save the Children.

Similar challenges extend to education, with many children like those of Falmata Kolo unable to attend school post-resettlement due to a lack of facilities.

The state’s initiative to resettle displaced persons, promising ₦954.7 million in support, appears insufficient as residents still experience persistent hardship. Figures like Munye Ali and Kaka Ali Fannami call for better education infrastructure and healthcare.

Despite receiving some aid upon initial resettlement, long-term necessities, particularly in health and education, remain unmet, prompting calls for increased government intervention.