Voters are understandably perplexed by Kamala Harris’ economic agenda, on which her campaign has offered little substance and little more than a string of vague promises. But when you follow the policy breadcrumbs, the vice president’s intentions become clear: She plans a continuation of the same economic policies we’ve seen over the last four years.

The weirdest thing is how similar many of her proposals are to those of Donald Trump.

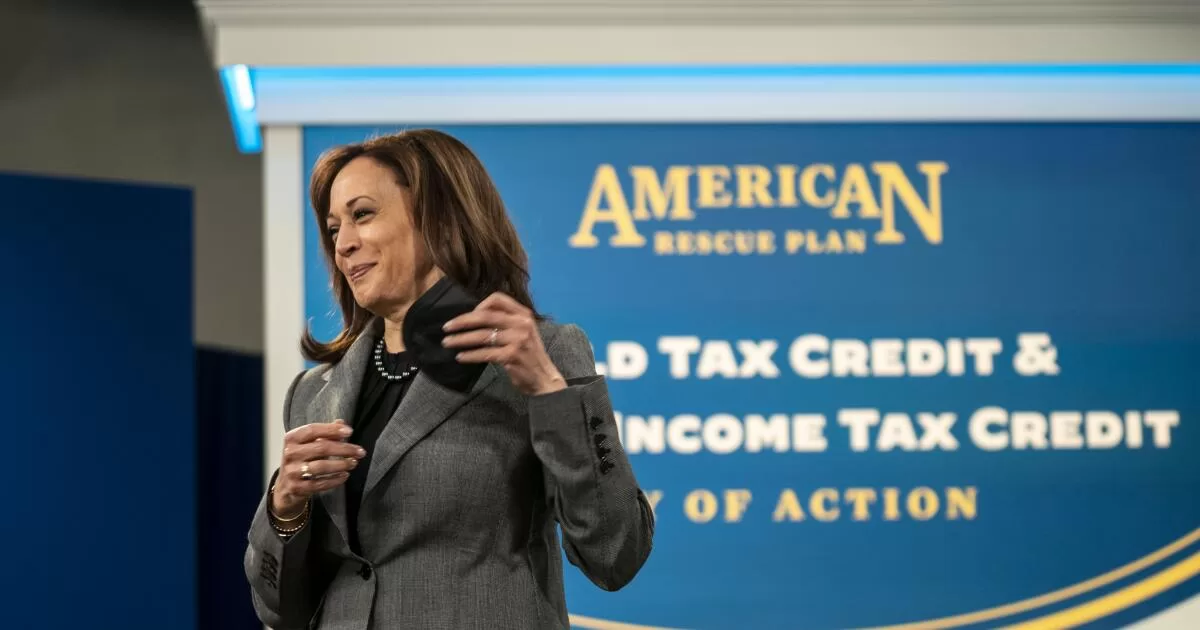

The Harris-Walz campaign policy booklet is light on substance but rich in tax credits for small businesses, first-time homeowners, and other selected industries. Harris wants to dramatically expand the child tax credit, especially for the first baby. She also wants more credits for housing developers and Obamacare customers.

Her campaign is copying the Biden-Harris administration’s playbook of granting large tax credits and deductions to many special interests. Legislation under the current administration unleashed what could cost $1.8 trillion over 10 years in energy subsidies alone. Meanwhile, the CHIPS Act extended additional tax credits to huge semiconductor companies, including Intel. Tax subsidies in 2021 amounted to $1.2 trillion, which shows how much previous administrations also liked handing out tax subsidies. But the Biden-Harris administration certainly expanded them dramatically; they now stand at $2 trillion.

Former President Trump also wants to hand out new tax credits and deductions left and right. He wants to cut income tax on tips (Harris embraces this too), tax credits for family caregivers and an extended child tax credit, and he wants to “promote homeownership through Tax Incentives and support for first-time buyers,” according to his campaign platform. He also wants to add tax credits for domestic manufacturing in ways that closely resembles the CHIPS Act, which some Republicans supported. Trump has also promised to exempt Social Security benefits from taxes and overtime pay.

While tax credits might sound good to voters who could benefit from them, they are a bad deal for taxpayers and the economy. They usually don’t grow the economy, because they often don’t encourage work, savings or investment. When they do encourage those things, tax credits can subtract from growth by directing capital and effort toward activities picked by the government for political reasons, rather than those picked by investors and consumers for sound economic reasons.

Tax credits are also quite wasteful, as many reward activities that already happened or were going to happen with or without the incentive. Most projects that received the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits were announced well before the credits were created.

In the worst-case scenario, tax credits create disincentives to work. Take both candidates’ extended child tax credit. Harris would like $6,000 for the first baby and $3,600 for subsequent kids. Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, has floated the idea of a $5,000 per kid credit. (Neither has a plan to pay for it.) The credit would sit atop some 80 existing welfare programs — many already targeting families — and would dispense with work requirements. Parents who don’t make enough money to pay federal income taxes would receive some cash from the government.

Research by economist Kevin Corinth shows that “families with little or no earnings are already eligible for tens of thousands of dollars in government benefits.” Adding more cash may be seen as helpful, but disincentivizing work leads to negative outcomes for families with children at the highest risk of being— and remaining — in poverty. Economists have shown that parental work, not government welfare, is the best way out of poverty.

Harris’ $25,000 tax credit for first-time homeowners would also increase prices. There is widespread agreement that high housing prices largely result from restrictions on housing supply caused by too many rules and regulations. Without dramatic changes to city, state and county regulations, this federal subsidy would further jack up the price of housing by boosting demand while doing nothing to increase ordinary Americans’ access to housing. The same would be true with Trump’s proposal. (According to the Republican platform, if reelected, Trump wants to “promote homeownership through Tax Incentives and support for first-time buyers.”)

As for tax credits directed toward corporations, you’ve perhaps heard a different name: corporate welfare. Study after study finds that a vast majority of these credits go to a relative few large and well-connected companies. For a recent example, the Philanthropy Roundtable’s Jack Salmon looked at the tax credits extended and expanded spending under the Inflation Reduction Act and found that three-quarters of benefits went to 15 large corporations.

Basically, Harris wants more of the same unfair, unproductive tax handouts. And Trump seems to agree with that plan. Worse yet, neither of them have a plan to pay for these handouts. This is incredibly irresponsible when we already have a $2-trillion deficit that would rise to $4 trillion within 10 years under current policies.

The other troubling approach is Harris’ support for policing pricing practices at grocery stores. America’s economy is resilient when prices are determined by a push and pull between producers and consumers.

Food prices have increased dramatically in the last four years, but not because of price gouging or corporate greed. Instead, this highest inflation in four decades was brought on by the federal government’s decision to flood the economy with spending and stimulus and the Biden administration’s refusal to scale back as the COVID-19 pandemic waned. Artificially low prices will lead to empty shelves and quality deterioration.

Harris also wants to cap banking and credit card late fees as part of a larger effort to eliminate misleadingly labeled “junk fees.” This might sound good, but once the government forces companies to lower fees, delayed payments will increase, making lending money riskier. When that happens, the only tools left for credit card companies to manage risk will be higher interest rates — which means higher costs even for responsible borrowers — or outright denials of credit cards to low-income households.

Trump too favors price control, as he now wants to cap credit card interest rates at 10%.

There are other similarities. Harris hasn’t made imposing tariffs the center of her campaign as Trump has, but the Biden-Harris administration has kept much of Trump’s tariffs and has added others to the mix.

One area where they sound different is taxes. While Trump wants to extend the tax provisions of his 2017 tax cuts that are expiring at the end of 2025 as well as cut the corporate income tax further, Harris is embracing the Democratic talking point of making rich people pay “their fair share” and not hiking taxes for those making less than $400,000. However, the plan she lays out will inflict harm on ordinary workers and consumers. Take her plan to increase the corporate income tax rate to 28%. Studies show that the bulk will be shouldered not by corporations, but by their workers in the form of lower wages and by consumers in the form of higher prices. Such a tax hike could well slow economic growth, which hurts lower-income people the most.

And many of the tax credits Harris proposes (or supported during the Biden years) are likely to benefit richer taxpayers. The extended child tax credit isn’t targeted at low-income families; most of the benefit will go to families earning higher incomes. Electric vehicle tax credits have always mostly gone to taxpayers with incomes above $100,000. That will continue. And while the skinny policy book lacks detail, I’ll wager that Harris will support ending the cap on the state and local tax deduction — a tax break that chiefly benefits high-income taxpayers in high-tax states. Trump has already indicated that he would eliminate the cap.

In the end, Harris’ economic plan is a familiar, ineffective formula of tax credits, corporate welfare and government intervention all over the place. Unfortunately, Trump is offering much of the same.

Veronique de Rugy is a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.