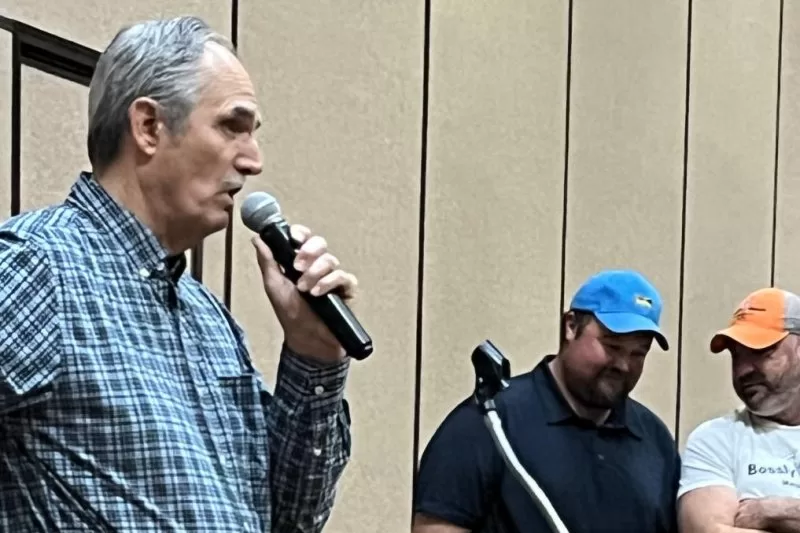

Ed Fischbach, a landowner from Spink County, SD, and member of the South Dakota Easement Team, speaks out against RL 21 during a landowner meeting in Aberdeen, SD, in July. Photo courtesy of Ed Fischbach

Oct. 4 (UPI) — The rights of landowners and local control are on the ballot in South Dakota as Summit Carbon Solutions seeks to build a carbon pipeline across the Midwest.

Despite South Dakota’s Public Utilities Commission denying Summit’s application to build nearly 500 miles of pipeline through South Dakota, the state legislature approved a bill that could help the company push forward with its plans.

Referred Law 21, or Senate Bill 201, would allow counties to impose a $1 per foot charge on CO2 pipelines if they received 45Q tax credits in the prior year. Revenue from this could be given to property owners throughout the county in the form of tax relief. It establishes some requirements for pipeline installation such as minimum depth and operator responsibility for damage to drain tiles, leaks and failure.

The 45Q federal tax credit is meant to incentivize decarbonization by industrial power plants. It is available for 12 years after a company puts carbon capture equipment into service. The deadline to begin construction on qualifying projects is 2032.

A coalition of landowners has risen up to challenge the bill by putting a citizen-initiated referendum on the ballot.

The bill was signed by Gov. Kristi Noem on March 26 and the coalition had 90 days after to collect about 17,500 signatures for a referendum to be placed on the ballot. It collected more than 34,000 and about 92% were validated.

“It’s nonpartisan,” landowner Ed Fischbach, member of the South Dakota Easement Team, told UPI. “I’m working with people I never thought I’d be working with before. We don’t agree on anything else. But this is about property rights and decency. We have liberal Democrats and far-right MAGA Republicans working together on this one goal.”

Rep. Roger Chase, a Republican, told UPI that RL21 will bring an economic impact to the entire state.

“Innovation is key to South Dakota’s growth, and that’s why I’m voting Yes on Referred Law 21,” Chase wrote in an email. “It’s not just about farming-it’s about driving economic impact across the state, creating more jobs, and strengthening county services. This is an opportunity to invest in the future of South Dakota, and that’s why my vote is a Yes on RL21.”

The bill was referred to by the legislature as the Landowner Bill of Rights. However, opponents of the pipeline have come to call it the “Summit Bill of Rights,” as it preempts local regulations and limits the Public Utilities Commission’s grounds for denying an application.

The coalition is encouraging voters to vote “No,” on Nov. 5.

A ‘Trojan horse’

“From the very beginning, my organization, we’ve referred to this bill as a Trojan horse,” Chase Jensen, senior organizer for Dakota Rural Action, told UPI. “There are a lot of mediocre benefits being tossed out, generally to obscure or to hide the explicit attempts to gut local authority when it comes to the regulation of these projects.”

There are two components of the bill that pipeline opponents mainly object to: The preemption of local ordinances and the apparent directive for the Public Utilities Commission to approve applications such as Summit’s.

Jensen is also concerned that counties will not be able to impose taxes on future projects if they are built after the 45Q tax credit deadline.

“This is a surgical attack on the mechanisms that kept this company from doing whatever it wants,” Jensen said. “It is intentionally ambiguous but basically they can claim that something that has to do with energy, commerce or transmission deserves to be permitted.”

Jensen argues that the bill puts the onus on counties to prove their ordinances are legal, rather than defending them after they have been challenged. It is a reversal of order that he likens to flipping the burden of proof.

“The impact of this is pretty tremendous,” he said. “What we’re saying is we assume everything passed locally is going to be restrictive and local governments are bad actors. So they need to bear the burden of proof to the Public Utilities Commission.”

Path to the ballot

The path to the ballot was more than three years in the making, according to Fischbach. He has been referred to as the “godfather of the pipeline fight.” He launched his opposition to the Summit pipeline in July 2021, after receiving a letter from the company that included a map of his property.

“They tried to ram it through really fast,” Fischbach said. “I started talking to other neighbors and we went to public meetings Summit had. We said we need to organize an opposition to this thing. Nobody trusted this company.”

Landowners in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota and North Dakota have given testimony during public hearings that allege Summit has not been transparent in its attempt to commandeer permission to build on their land. Attorney Brian Jorde, representing more than 1,000 landowners in lawsuits against Summit, said his clients have described an aggressive pressure campaign by Summit that included complaints of harassment.

“It’s a consistent pattern,” Jorde told UPI. “There’s hours of testimony in trials I’ve had of that type of behavior.”

Summit scored a legal victory in the South Dakota circuit court system, allowing it to perform surveys without landowner consent. The state supreme court reversed the decision in a 42-page opinion.

The most significant part of the supreme court ruling was that the court found Summit is not a common carrier. A common carrier is a business that offers a transport service to the public for a fee. Some examples include rail companies, airlines and public utility companies.

Common carriers have the right to exercise eminent domain.

The supreme court found that Summit is not a common carrier because the CO2 transported through the pipeline would be sequestered underground with no apparent productive use.

“The legislature’s decision to delegate the power of eminent domain to pipeline companies — must be understood to require a public use that actually serves the public,” the opinion reads. “A pipeline cannot become a common carrier simply by declaring itself to be one.”

It also found that Summit obstructed the landowners’ ability to acquire depositions and documents that were part of the circuit court case.

The South Dakota Public Utilities Commission listened to the concerns of county commissioners and landowners as it considered Summit’s application. The pipeline would span about half of the state of Iowa with branches in Minnesota and Nebraska. It would then cross South Dakota to reach a carbon sequestration site in North Dakota.

Several county commissions in South Dakota unanimously issued moratoriums on the pipeline and established ordinances that included setback requirements. Summit sued the counties, including Spink County where Fischbach lives. The lawsuits claimed that the counties violated federal law by imposing moratoriums.

“The commissioners didn’t budge,” Fischbach said. “They passed these ordinances and setbacks.”

In August 2023, Summit filed a motion requesting that the Public Utilities Commission overrule those local ordinances so it could build as it had planned. It withdrew the motion days later and, following an evidentiary hearing, the commission denied the application.

In its order to deny, the commission wrote that there were “material misstatements” in Summit’s application regarding its ability to comply with local ordinances. It found that the proposed route violated local ordinances and must be denied. It also denied an application from Navigator CO2. That pipeline project was canceled in October 2023.

On Jan. 31, the Landowner Bill of Rights was first read in the state legislature. On March 6, it passed the Senate by a 24-10 vote, then passed the House 39-31.

‘Political earthquake’

The coalition of landowners threw their support behind congressional challengers in the June primary. Six House and five Senate incumbents, all Republicans, were defeated.

“They were calling it the political earthquake in South Dakota,” Fischbach said. “We believe we have flipped the House of Representatives. We believe there is going to be all new leadership. We’re hopeful in the state senate.”

A number of prominent political figures have supported the Summit pipeline project. Bruce Rastetter, the founder and executive chairman of Summit Agricultural Group, is the former president of the Iowa Board of Regents. He is also one of Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds’ biggest donors. Summit was also a platinum level donor to Gov. Noem’s inaugural ball in 2019.

Summit employs former Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad, a Republican, as its senior policy adviser and Jess Vilsack, son of Prsident Joe Biden‘s Secretary of Agriculture and Tom Vilsack, as its general counsel.

Former South Dakota Secretary of Agriculture Walt Bones owns land on the pipeline’s proposed route. He emailed UPI comments supporting the project.

“RL21 proactively supports landowners, like our family, that could be impacted by this project which will positively affect our local Ag economy,” Bones wrote. “If we can add value to our 800 million bushels of corn, the potential impact is massive. This is a huge opportunity for South Dakota, we need to make it happen.”

If RL21 passes, Fischbach and Jensen expect Summit will file a new application quickly.

“At that point, it begins again,” Jensen said. “There will be a new push for counties to pass ordinances, even though their legal standing will be diminished. Citizens will continue to lobby their local governments. We would have to fight just as hard to enforce them.”

If it fails and the coalition’s bid is successful, they plan to push for eminent domain reform in the next legislative session.