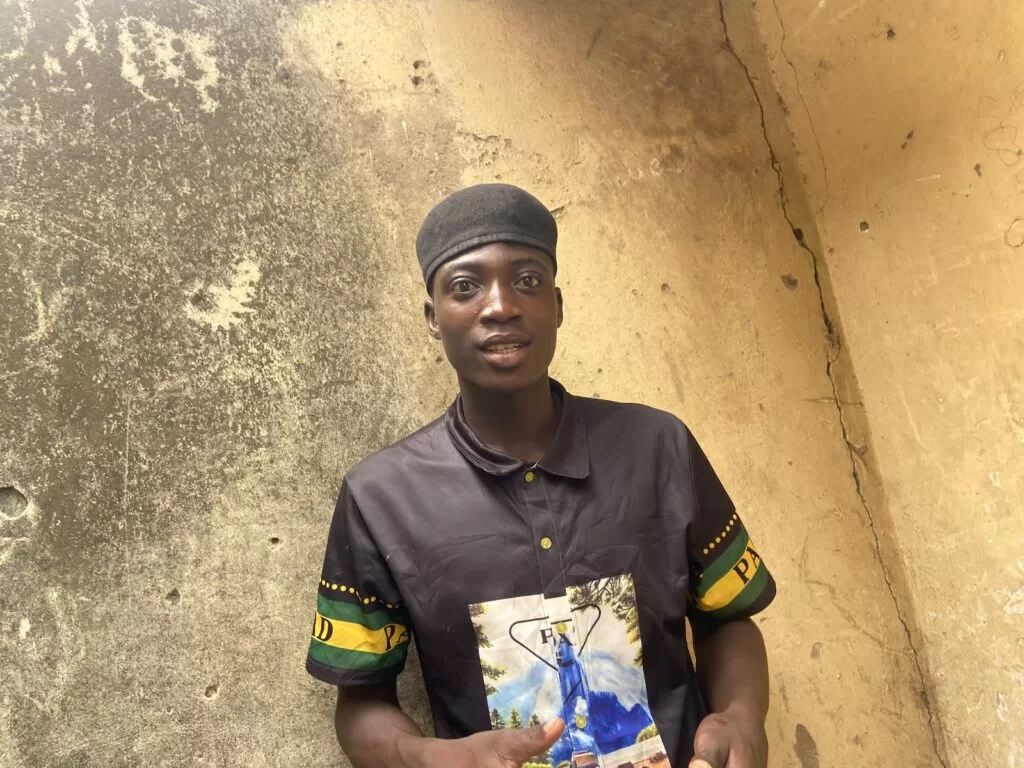

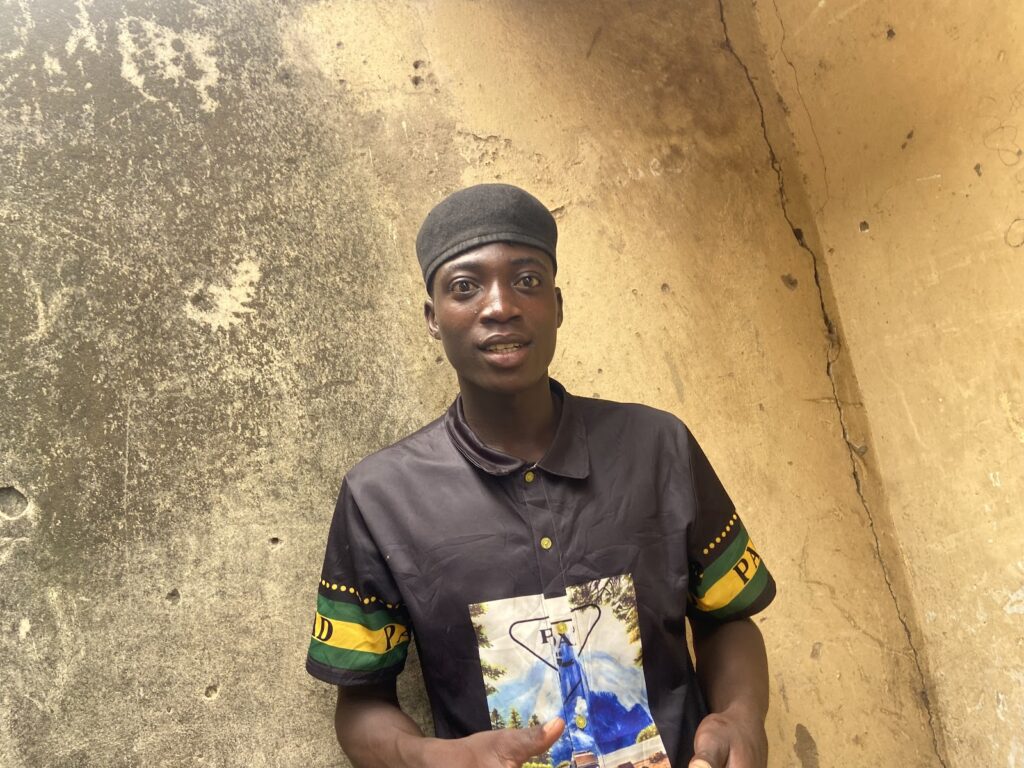

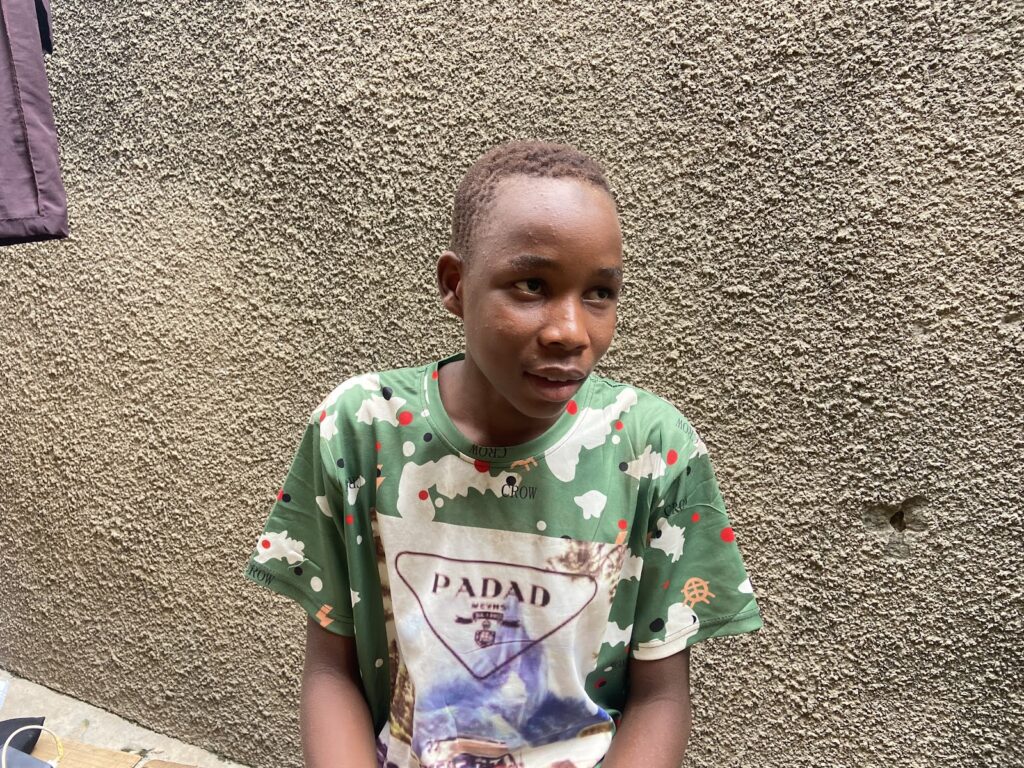

The dim light of the boys’ quarters cast a long shadow over his forehead as he walked into the tiny room of a ‘face-me-I-face-you’ apartment in the Damba area of Gusau, North West Nigeria. His eyes, dark and watchful, flicked between the scar on his right hand and the broken tiles sprawled across the floor. He would later tell me the story behind it. Bashir Suleiman is a Yan Arile, a catchphrase in Nigeria’s rural Zamfara used to describe young men who had left their dusty vicinity in search of fortunes that have grown increasingly scarce in the northwestern town.

It’s mid-March 2021. Bashir had just finished his secondary education when he learnt from friends about the land where “honey and milk” flowed ceaselessly and everyone could scoop to their fill. His father wanted him to follow in his footsteps immediately after school. Farming is the family’s main source of livelihood. Then, it was lucrative and flourishing. Zamfara is one of the country’s breadbaskets. But Bashir wouldn’t want to toe that path. One of his uncles was attacked on his farm by terrorists and spent months on the sickbed before he finally drew his last breath. Farming in rural Zamfara has become an extreme sport for many because of the activities of terror groups who have made the region another theatre of violence.

Bashir had other plans in mind; he would do his father’s bidding and work for some time to gather money for the journey to this promised land. So, he got a bike on a hire purchase. The 25-year-old worked his nose for over six months to gather about ₦120,000 ($72). He had paid off the motorbike, too.

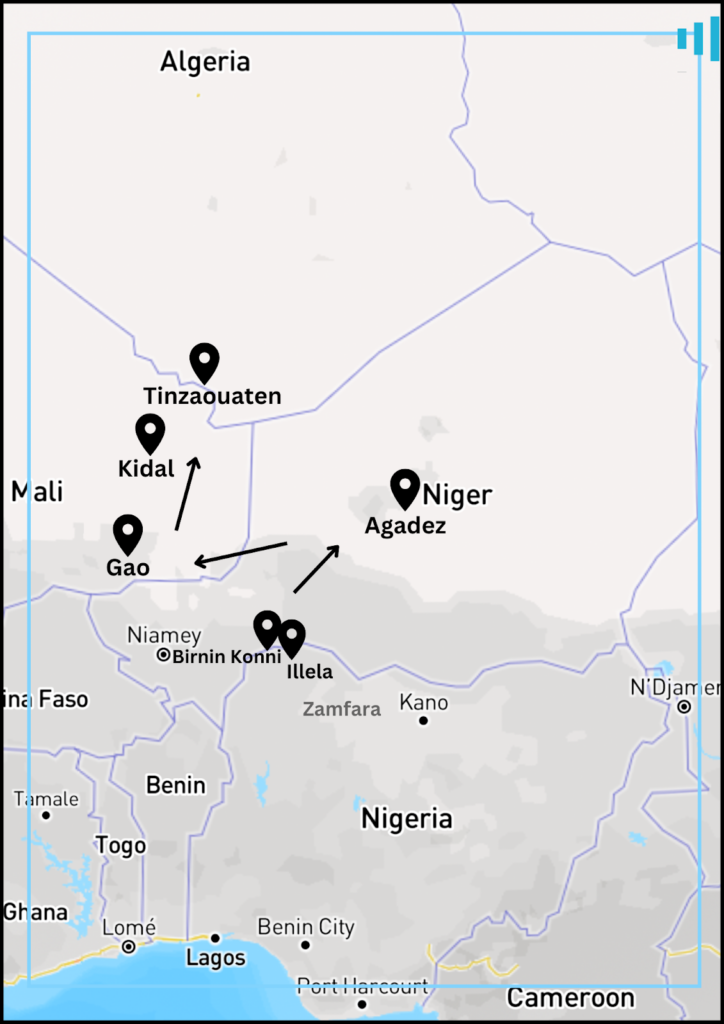

In late 2022, Bashir and Yellow — a lanky colleague in his early twenties — were ready to journey through the dunes and the isolated watering points of the desert to Mali, their promised land of vast fortunes. It’s cheaper by road. Gold is Mali’s most important export product. The West African country is the continent’s third-largest producer of gold after South Africa and Ghana. Artisanal miners run the bulk of its thriving gold mining industry, piggybacking on the sweat of migrants, most of whom come from neighbouring countries like Burkina Faso, Guinea, Niger, and as far as Nigeria.

Trade and travel within and across the Sahara are as old as time. The movement takes goods and people from the belt of West Africa up to the coast of the North and vice versa. Many migrants also ply the route to reach Europe through the Mediterranean in search of greener pastures. HumAngle has learned that seasonal miners who come from the Niger Republic to work in the mines across Nigeria’s North West and parts of the north-central region often link young men in these communities to their counterparts in Mali.

In Africa, accurate statistics about migration are hard to come by. The United Nations says no fewer than 31 million Africans live outside the country of their birth. Most of these travels are within the continent — only 25 per cent go to Europe. This is made more accessible by laws promoting freedom of movement and trade within the continent. In West Africa, a similar free movement agreement allows anyone from the member states to travel within it without applying for a visa, making movement within the regional bloc easier and cheaper.

With a bag full of dreams, fewer clothes to avoid suspicions, and some food, the journey began just a few walks outside the central motor park in Gusau, Zamfara state capital. A minicab was waiting to transport them to Sokoto. The northwestern state is approximately 103 kilometres from the neighbouring Niger Republic. The bustling border town of Illela is just a stone’s throw from the Birni-N’Konni area of Niger’s Tahou region.

“Where is the job in the country?” Bashir protested. He had recently returned from a trip to assist his family during the annual planting season. “It might be a little dangerous working in the mining sites, but it’s nothing compared to staying here idle and getting killed by the terrorists.”

Since the North West conflict escalated in 2011 and disrupted the economy of the agrarian region, forcing major businesses and farmlands to slow to a crawl, the area has become a lair of illegal labour migration to the Sahel — a region that accounts for large chunks of global terrorism deaths since 2021. Many of its young boys, like Bashir, are trooping to countries like Mali, where they engage in artisanal gold mining activities.

Most of the landlocked country’s gold mining regions lie in Western and Southern Mali. There are also mining sites in parts of Northern Mali where Azawad rebels and Al Qaeda-linked jihadists operate. In January, Russian fighters — formerly Wagner mercenaries — took control of the Intahaka gold mine, the region’s largest artisanal gold mining site, which had been disputed for many years by various armed groups.

The precise number of small-scale mining sites is unknown to the Malian government. But statistics put it at over 350 across Western and Southern Mali. The figures exclude the rebel-controlled territory of the North.

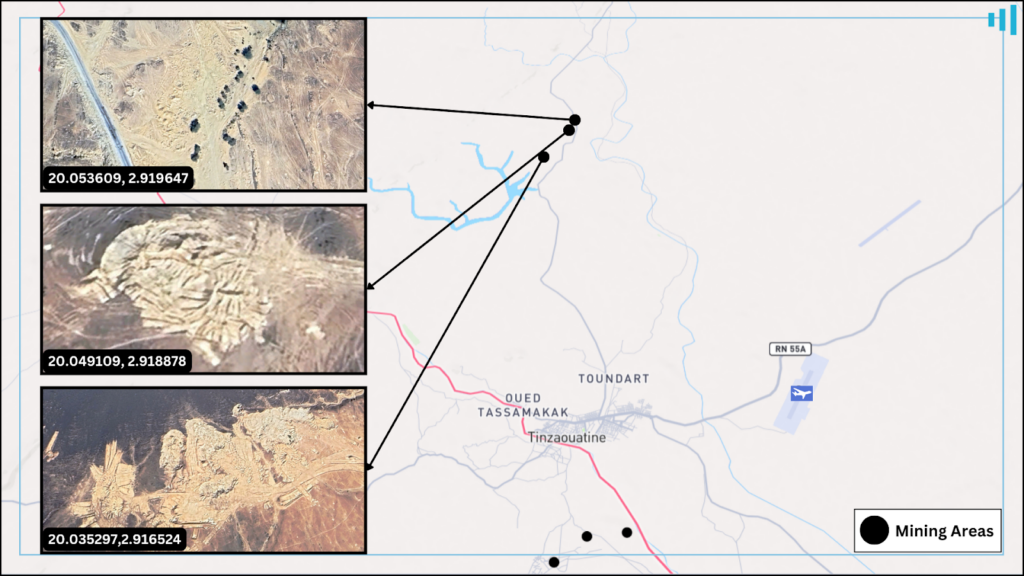

Satellite images, corroborated by multiple sources we spoke to, show that most Nigerians, especially those from Zamfara, work in the three major mining sites in the rural Tinzaouaten commune, located far North East of Mali on the border with Algeria. When Bashir got to Mali, they drove to Kidal. Set on the dust of the desert, Kidal is a crucial stopover between Mali and Algeria. Most Hausa-speaking migrants — Nigerians and Nigeriens — stayed here. The shared identity and language helped them to settle and get along with their ‘brothers’, who introduced them to other miners.

“The miners would come to us and ask if there are those willing to go to the forest to mine. They would inform us the number of miners they needed and the condition of the mines if they are old or new,” Bashir paused to gobble three awaras (cheese), much to the annoyance of Yellow, who frowned at his audacity.

“Some, however, are not always honest,” he continued. This often cost them their lives. Mining accidents are common in the country as most unregulated miners use unsafe methods to dig for gold. At least 73 people were killed in January after a tunnel collapsed in a gold mine in the south-western Koulikoro.

“There is no fixed income. The amount of gold that was mined would be divided into three. They take two and the miners one. For instance, if what was gotten is worth ₦100,000, they would take ₦60,000 and leave the miners with ₦40,000, which we would then share depending on our numbers. We were often given the choice of either being paid in gold or money. We always choose the latter because they are the only ones who know where to sell the gold.”

The migrants are provided with basic essentials like food, water, and tools. He says the working conditions leave so much to desire. Many only stayed because they could not afford to return home without the promised riches. Some workers dig shafts and work underground with torches strapped to their foreheads. Some are charged with pulling up and crushing the ore, while others are to pan it for gold. Many of them suffer severe neck or back pains and risk long-term spinal injury from carrying heavy objects. Some have also sustained injuries from falling rocks and sharp tools or fallen into shafts.

“If you offend them, they would hit you or take you to the rebels who would then prosecute you. And if they met you not working, they would flog you and force you to work. They wield different types of guns. We often work overnight. We take no breaks. And if we protest, we would be abandoned there,” Bashir recalled.

Through the control of sprawling mining sites, taxation and securing transportation routes, gold mining serves as the lifeblood of terrorism for rebel forces and jihadists in the central Sahel region and other parts of Africa. The mine sites, particularly in areas where government forces are absent, are not only a hideout but a revenue source with which they recruit new members and buy arms and explosives to continue to exert control. In some areas, they ordered gold miners to sell only to them at fixed rates. Much of this is smuggled out of the region, often to buyers in the markets of Dubai, Switzerland, and India. In 2022, a whopping 435 tonnes of gold — mainly from the red-dust open fields of Mali, Ghana, and Zimbabwe — were illicitly exported from the continent, primarily to the United Arab Emirates.

Between 2012 and 2022, the smuggling more than doubled, so much that 2,569 tonnes of gold exported from the continent into the UAE was not accounted for or declared for export in most countries on the continent. The average price of gold over these years amounts to a total value of $115.3 billion. Much of this returns to the conflict-ravaged zones where Bashir and Yellow work, financing and blowing the ember of conflict.

“Gold mining has become a major source of funding for jihadists and other armed groups operating in the Sahel,” Oluwole Ojewale, an analyst at the Dakar-based Institute for Security Studies, told HumAngle. “Most often, this is a result of the very low government presence in these areas. The armed groups turn to different sectors for funding. Previously, it used to be cattle rustling, but the major source at the moment is gold. That’s why hotspots in the Sahel that have become bases for jihadist activities are, in most cases, mineral-bearing communities with no government presence.”

The crossfire

Northern Mali, where most Nigerians go for mining, has been under the control of jihadists and the Azawad movements, an alliance of mainly Tuareg rebels seeking independence for the region since 2012. Kidal became one of the initial territories to be seized by the rebels — and their stronghold too. Since the military took over power about four years ago, the junta has prioritised stamping their authority over all parts of the country. A 2015 peace accord, designed to integrate the rebels into the army and decentralised state power, was scrapped early this year, further plunging the country into a free fall.

Government forces, supported by Russian fighters, took over Kidal late last year and have been trying to reclaim other rebel-controlled areas — a daring move that’s seen migrant workers like Bashir and other civilians repeatedly get caught in crossfires.

In August, at least 21 civilians, including 11 children, were killed in drone attacks in the town of Tinzaouaten along the border with Algeria. The drone had hit a pharmacy, leaving many people injured. In 2024 alone, analysis of media reports of casualties of drone strikes carried out by the Malian forces shows that no fewer than 68 civilians, mostly children, have been killed so far.

“A lot of young men from Zamfara worked in these mine sites, most of which are controlled by the Azawad rebels and JNIM Al-Qaeda affiliate,” a source who is familiar with migrant smuggling in the central Sahel region told HumAngle. He asked not to be named due to perceived security risks.

“When the Malian force and Russian mercenaries tried to seize the city, the rebels used these mines to hide their forces, eventually ambushing the Malian/Russian fighters. Right now, the mines are deserted because a Bayraktar Akıncı drone bombed it, and some Nigerians lost their lives.”

Back at home, Bashir removed the fading black beret on his head and perched it over his knee. They were about to step out for the evening five-a-side football game to unwind from the long day they had working on the farm. Bashir says he would be returning to Mali after the planting season. His father, undoubtedly worried, still wishes his boy stays home and forges a path for himself with the little he’s been able to amass.

“Embarking on the journey is a gamble. It’s either we make it home, or we don’t. I have seen people face a lot of things. There was a Nigerien who got exploded by a bomb while we were mining. His face got damaged, and he lost his arms. Most of the time, when these things happen to our people, I think about returning home.”

But that is not enough to discourage him.

Pushed to the brink

Rihannatu Isa could not convince his 23-year-old son, Aliyu, to return home. And that’s because Aliyu was trapped in the shaft when a tunnel collapsed on miners in one of the sites in the Tinzaouaten side of Algeria. His body was ‘swallowed’ by the rubble.

It’s 6:50 p.m. on a Monday. The clouds gathered, and thick wisps of black smoke from a burning tyre filled the air. Rihannatu leaned against the wall at the entrance of her apartment in the Premier area of Gusau. She had just seen off a relative who had come to visit her when she suddenly welled up. Ahmad, Aliyu’s friend who came with us to see her, was in the shaft with him when the tunnel caved. He reminded her of Aliyu’s meekness. He shared a striking resemblance with him in complexion and height. They’re both something around 5’7 tall and dark-skinned.

“They said the sand swallowed him,” Rihannatu started. The tears were now rolling down the cliff of her face. “He was a good child. Among all my children, he was the most supportive, providing for me. Life was easy with him by my side.”

Before Aliyu embarked on the trip through the ridges of sand that led to the high country, he was a carpenter. He managed a makeshift stall inside the furniture market in the capital. At the market, he heard talks about what the landlocked country portends. Riches and lots of wealth from precious metals. At first, Aliyu wouldn’t give it much thought. He cared for his siblings with the little he got from the business. But in September 2021, when terrorists loyal to notorious kingpin Bello Turji kidnapped his father (a commercial driver), life took a bitter turn.

“His father spent about three months in the hands of Turji. There was no service (phone network), and we heard nothing from him. During this period, Aliyu would go into the bush to find a way to speak with the bandits. We had to eventually find a negotiator who got them to agree to a ransom of ₦3 million ($1,800).”

The family sold some of their belongings and raised about ₦1.8 million for the release of their father. “When the person who went to pay the ransom came back, he told us the bandits refused to release Aliyu’s father because it was three of them that were kidnapped, so they can’t release one person except for the total sum of ₦3 million was paid for all three.” A knot nested in the woman’s chest, making her struggle to stitch the timeline of the incident together.

One Sunny afternoon in 2022, after more than three months in the forest with his abductors, Aliyu’s father was able to escape, but life wouldn’t return to the way it was for the family. He died a few weeks later from the torture he suffered when he was in the forest with the terrorists. His death was the last straw. Aliyu knew something had to give way. Seeing his family run from pillar to post for daily sustenance distressed him. So, he bit the bullet and swallowed it whole: it’s either the Sahel way or the Sahel way. He would dig to his fortune, too, like those before him.

“He told his younger brother not to inform me about his plan until he got to Konni. Then he called him to tell me to be patient and that he would be back in a short while,” she said. True to his words, Aliyu returned after nearly a year working the mines of Mali and Algeria, but he would only stay for a few weeks to fast during Ramadan. That was in March 2023.

Aliyu was driven by the will to escape the poverty that held his family in the jugular. According to the country’s statistical agency, the North West is home to some 45 million people living below the poverty line. In Zamfara, about 78 per cent of the population are poor.

A few days after Eid al-Fitr, which marked the end of Ramadan, he informed Rihannatu, this time, about his plans to return to the resource-rich country but promised to check in regularly. During the first trip, he had no time to call home. He was busy working the mines. And the telecom service was poor in the region. Four months after he left home, Aliyu called. She couldn’t hear him properly, so he told Rihannatu he would call back the next day. His hoarse voice was, however, like a balm that soothed her worried heart.

“He was talking, but I could barely hear him. I told him that the service was poor, so he said that he would call me later. That was the last time I spoke to him. He never called back again,” she recalled. About four days later, she would receive another call that left a big void in her life. Ahmad, Aliyu’s younger brother (not the colleague), came home to relay that his brother had asked her to call him. It was an unusual message. “He had never asked us to call back. Instead, he used to be the one to call us. I asked him to take me to the person who gave him the message. We started walking, and then I stopped and told my younger son that Aliyu was not alive. Aliyu is dead. I could feel it.”

Rihannatu nestled the feeling into herself and hoped she was wrong. Her mouth wore supplications. But her gut was right. Aliyu was no more. Not so long after they got home, now whimpering silently, the sixty-year-old got a call. The caller asked that the phone be given to a man. Her body went cold. “I remember all that Aliyu did for this family. He was a provider. We were like siblings. We played and laughed together. I’ve known the pain of losing a mother, father and husband. Aliyu’s left me devastated,” she said, her voice quaking with grief.

Rihannatu’s hand trembles anytime unfamiliar faces visit her. “When I see strangers coming to my home, I get disturbed thinking that they have come to report the death of another child,” she explained.

For her, the certainty of loss weighs heavily, but for Amina Yusuf, 55, the uncertainty haunts her. While Rihannatu’s family has had no choice but to confront their grief, Amina holds on to hope, waiting for the return of her son, Ibrahim. The 24-year-old left home one Thursday in March last year to work in the mines in Mali.

For nearly a year now, his family has not heard from him. There were hearsays from returnees that he was left in the mines, but his whereabouts have remained unknown. Before his departure, Ibrahim sold call cards and phone accessories in the capital. Like others, he also kept his travel plans from his family.

“He had already decided he wanted to leave, and he knew if he told me, I wouldn’t have allowed it. So, having made up his mind, he started behaving strangely with the business. He would go to another business, leave, then come back home and lie down. I didn’t know he was selling his belongings and saving money for his travels,” Amina said. She sat cross-legged in one corner of the passageway that leads to the community’s mosque. She still held to the rusty letter he wrote, asking for her forgiveness. It’s one of his items that gives a ting of hope Ibrahim is somehow alive in the wild.

Early this year, Ibrahim called home. It was sudden and brief. Amina held the Tecno phone to her ear and tried to feel the heavy fall of his voice. She still couldn’t believe she was speaking with her son. It’s the longest she’s gone without him.

“He said he was coming home because they had encountered a problem, and he needed money to travel back. Since I didn’t have money – I only had ₦2,000 – his older brother was the one who went out and sent him some money,” she coughed. Amina blew her nose before adjusting the deep-yellow hijab she wore.

Since that day, she’s not heard from him again.

When some of his friends returned, Amina was eager to hear from them. She sought them out, but there’s not much information about him. “Some say they saw him here, others say they saw him in the forest, and some say they don’t even know him.” But she’s not giving up, at least not yet. “All I want is for God to keep and guide him home safely. There’s nothing else for me than embracing him with my two hands.”

Between hard rocks

Ahmad Shuaibu, 22, has nothing to show for his two-year stay in the gold mining sites along the Mali border with Algeria. In 2021, while he was just 19 years old, Shuaibu took a daring leap after a fallout with his iron-wielding boss, whom he apprenticed under in the state capital. He had learnt the routes to Mali from his friends who came back with tales of the landlocked country.

A week after the fallout, with his life savings of just ₦40,000 and sheer will, Shuaibu hit the road alone. He would begin the journey in Gusau through the country’s porous border with Niger Republic. He avoided the official gateway between the neighbouring countries in Illela, Sokoto. Nigeria’s porous border with Niger, around 1,608 kilometres long, has been a burrow for terrorists and smugglers who snake in and out of the country outside the purview of security agents.

“At that time, I used to save some money with my mother from my welding work. It was what I used to foot the transport fare,” Shuaibu beamed eerily, reminiscing about old times. “When I got to Illela, I took a motorcycle and crossed to Konni. We went through the forest, not the highways where security forces are stationed,” he paused. His friends looked sharply at him, presumably hinting at him to be cautious of what he revealed.

When Shuaibu got to the northern Nigerien city of Agadez, a busy transit town for migrants hoping to reach North Africa and Europe, he realised he was running out of money to continue the journey. So, he stayed in the city for almost seven months doing menial jobs to proceed to the resource-rich country where his friends were waiting for him.

“We lived on the border that divides Mali and Algeria. However, the mines are located in Algeria. But it was risky,” he confessed. He’s seen most of his people from Zamfara suffer life-threatening injuries — and sometimes death. “People got buried in the mines. I heard about Lauwali. We were in the forest when we were informed—even that of Aliyu. We were so devastated by the news. Those who witnessed it were so traumatised that they could not even eat.”

Last year, he decided to return home. “It was the best decision for me at the time,” he sighed. “Some people spend so many months before contacting home. However, I don’t go beyond six weeks. Maybe that’s what helped me to reconnect with home when I did.”

But life hasn’t been rosy lately. Most Nigerians are writhing under a spiralling cost of living crisis. The country has been experiencing its worst economic crisis in decades, partly due to reforms introduced by President Bola Tinubu, who came to power over a year ago. Floating the currency and removing fuel subsidies have caused more hardship in a country where 133 million people live in poverty. Food prices have more than doubled in the past year as a soaring inflation rate hit 32.15 per cent in August.

“I spent about two years there and acquired a satisfactory amount of money, roughly ₦5 million. But there’s nothing to show for it now. Very soon, I’ll go back because since I returned, I have not been doing anything. I even returned to my former work — welding — where I currently keep myself busy,” he told HumAngle.

Wilson Erumebor, a senior economist at the Nigerian Economic Summit Group, believes the migration of young Nigerians is caused by a cocktail of many factors, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, which left a mark on the global economy.

“It is normal for people to move into and out of a country in search of a better life for themselves and their families. In Nigeria, especially since 2020, the key drivers of emigration cannot be unconnected with the harsh economic realities, reflected in a huge number of Nigerians living in poverty, the limited number of good jobs to cater for labour market entrants and high inflation, which has reduced the purchasing power of many Nigerians.”

Abdulaziz Isa, 24, wants one thing out of life: a future where his siblings wouldn’t have to dig through tunnels under the glare of gun-toting rebels or jihadists in the goldfields of the central Sahel region.

In 2021, when Abdulaziz left Gusau for Mali, like Shuaibu, he had just finished secondary school. As the eldest son, he was beginning to feel the weight of his family’s expectations. His father, once a respected Mallam, had been forced to abandon his work due to consistent bandits’ threats. Therefore, the responsibility of providing for his younger siblings fell squarely on his shoulders.

His job as an iron bender could not provide much. So, he pulled his meagre savings with some of his friends who were down for the journey to Mali. And they set off.

“I was sitting at home, and my business wasn’t prospering. My family also expected me to provide for them, but I couldn’t. That’s when I learned about Mali from friends. I gathered my savings and even sold my phone to make the trip,” he shared.

Abdulaziz sat in his small room in the Premier Road area of Gusau, fiddling with the thread at the top edge of the mat. It reminded him of the journey, fraught with robbers who stripped them of their possessions, leaving them with nothing but the clothes on their backs. “We had to stay in Agadez to work for months before setting off for Mali,” he added.

Now in Gusau with Shuaibu, after nearly two years in Tinzaouaten, the 24-year-old has resumed work as an ‘iron-bender’, but the rising cost of living has seen his income decline to a staggering trickle. “It’s been hard since we got back last year. Other people would have resorted to stealing for far less because there are no opportunities for young people like us. I have spent more than a year here and haven’t even saved up to ₦50,000.”

Abdulaziz scoured through his phone gallery before locking eyes with his friend, Shuaibu. He winked at him and signalled for them to leave. It was a little before sunset. But as they attempted to step out, Abdulaziz made a silent promise. He would strive to build a better life for his siblings and never let them walk the difficult road he had to travel.

“I believe I’m grown now, and I would feel bad if I couldn’t take care of my family. I have nothing else to do here, but I can do something there (Mali). I want to go back for a few months and build a life when I return.”

Additional reporting by Aminu Kwaccido.