Part 1

A young man’s grave sits on a cemetery hill. To reach it, his parents drive through serene, graciously shaded neighborhoods where they see him still. As a toddler, throwing bread to the ducks. As a sixth-grader, on a razor scooter. As a lanky teenager with a cocky sideways smile.

Fred Santos, the father, steers his Toyota Prius into Oakmont Memorial Park in the Bay Area suburb of Lafayette and follows the road to the summit. He parks amid the pines and oaks. He carries sunflowers as he and his wife, Kathy, walk to the spot.

LUIS FELIPE WATSON DOS SANTOS

June 27, 1986 — October 4, 2008

Mr. Personality

Family first and lots of friends

At 57, the father is a slightly built, unassuming man with thinning black hair and the hard-to-place accent of his native Macau, a former Portuguese colony off mainland China.

Pequenitates, people called him. “Little guy.” It was more than just a physical description. It seemed, in the world of his childhood, an apt description of his place.

Down at the bottom were families like his, scrabbling for a living on the tiny island. Up at the top were the deep-pocketed Tai-Pans, a Cantonese term for “Big Men.” Nobody was surprised when, in a collision between the two classes, power prevailed. It was the order of things, as inarguable as the grave, or a father’s need to die before his children.

In America, he learned, people were not resigned to this outcome. They built superstructures of law to prevent it. They railed against it. They told him things were different here. Mostly, they convinced him.

In a cage in Northern California lives another man’s son. To reach him, the father steers his gray BMW X5 through miles of rolling rye grass, past weather-beaten farmhouses and cattle ranches and goat farms, until he reaches the security kiosk at Mule Creek State Prison in Ione.

His face is familiar here, even to those who never saw it on the news. The cleft chin, the symmetrical features, the smile that seems to convey personal affection for everyone, however humble.

Fabian Nuñez, 47, a man once routinely referred to as California’s most powerful lawmaker, has been making the trip for five years. He knows to leave his cellphone and wallet in the car, to carry his ID and vending-machine dollars in a zip-lock bag.

After the short walk past an electrified fence to the check-in office, he knows to keep his toes behind a red line and to present his left hand for a stamp, which will identify him as a visitor — rather than an escaping prisoner — when he leaves.

He is divorced from his son’s mother, and he often comes here alone. He grew up in the gang-ridden barrios of Tijuana and San Diego, the ninth of 11 children, a gardener’s son. He learned to box to protect himself, and in the hope that his father, who loved the sport, might make time to attend his matches.

He blazed to power speaking the language of the underdog, in an accent that never lost its border-town echoes. He put his upbringing at the center of his political story. He rhapsodized about the great leveling power of America, where a kid who started life in mismatched hand-me-downs could go mano a mano with scions of privilege.

He became an immigrant rights activist, a Los Angeles labor leader, an assemblyman and finally the speaker of the California Assembly, the Democratic antagonist of the movie-star Republican governor and, later, something more improbable: his friend.

Metal detector. Door. Enclosure. Door. Walkway. Door. Guard. Hand scanner. And then the final door, opening into a communal visiting room filled with plastic chairs and the reek of microwaved popcorn. He carries a printout with his son’s name and ID number: NUNEZ, ESTEBAN ARMANDO AE1200.

The son will emerge from a side door in his prison scrubs and leather boots, at 25 already taller and broader than his father. Always, they greet with an embrace. They will play intense games of Scrabble, and discuss the family and the latest tech gadgets waiting in the world outside.

In a year and a half, the father will bring his son home.

“2:16 a.m. Saturday, Oct. 4, 2008

“We’re about to die! One of my friends might die right now! You need to send an ambulance as quick as possible.”

This is Evan Henderson, yelling into a cellphone. In the background of the 911 recording, someone can be heard screaming, “Please!”

“Please hurry,” Henderson says. “I’m stabbed in the back right now. My friend is stabbed in the chest right now. Please hurry.”

The 20-year-old San Diego State University student struggles to give the dispatcher the location: 55th Street near Fraternity Row, between the Aztec Recreation Center and Peterson Gym.

Three of his buddies are bleeding. Keith Robertson, 22, has been stabbed in the left shoulder. Brandon Scheerer, 24, has a fractured eye socket and a torn eyelid.

Luis Santos, 22, has collapsed in the bushes outside the rec center. He cannot speak. His friends huddle around him and press their hands against a knife wound in his chest.

“The person that stabbed you, where is he at?” the dispatcher asks.

“I don’t know where he’s at,” Henderson says. In the background, someone says, “He’s f— dying!”

“Do you know the people that stabbed you?”

“No, I have no f— idea who they were. They’re random. Random people.”

Scheerer tries desperately to flag down a car. One drives past, then another. In the background, he can be heard yelling, “Stop! Stop!”

“Was anything taken from you, Evan?” the dispatcher asks.

“My boy’s dying, my boy’s dying!”

“Was anything taken from you?”

“Nothing,” Henderson says. “I’ve got blood all over me. I’m really worried about blood loss. And my homey’s about to die.”

In the background, one of Santos’ friends can be heard begging him to live.

“Stay awake, Luis! Stay awake!”

The maroon Chevrolet Cobalt raced north through the dark on Interstate 5, out of San Diego County and through Orange and Los Angeles counties. It climbed the Tejon Pass high into the Tehachapis, descended into the San Joaquin Valley and kept going.

The young men inside took turns driving. They pounded power drinks or slept off their hangovers, slumped against one another in the crowded compact. Lil Wayne blared from the stereo.

There was Esteban Nuñez, 19, the product of Sacramento suburbs and private schools. Three years earlier, in a public television show that profiled his father’s rise, the Nuñezes had been portrayed as the epitome of Latin warmth: Spanish-language karaoke, dancing, big family meals. Esteban had looked as sweetly awkward as any teenager in the shadow of an important dad.

Lately, he had been affecting a ghetto-gangster mien. On his muscular right shoulder, he wore a tattoo of a hazardous-material sign — the emblem of the Hazard Crew, a posse of buddies whose violent glories, real or imagined, he extolled in rap lyrics.

He liked to post online photos of himself with alcohol and knives. In one image, he cheerfully aimed a knife at a cat; in another, he seemed about to impale a frog.

Now, in his pocket, he carried the knife he had used in the fight.

Crammed into the car with him for the 500-mile drive to Sacramento were friends he had assembled for a weekend trip to San Diego. There was 19-year-old Rafael Garcia, small and meek-looking, a judge’s son from Sacramento, another private-school kid who rapped and wore a Hazard Crew tattoo. “Little G,” people called him.

There was Leshanor Thomas, 19, a former high school basketball standout and a classmate of Nuñez at Cal State Los Angeles. He drove much of the way — the car was his — steering with his one good hand. The other was swollen from the fight.

There was Ryan Jett, 24, who had been taking business classes at Sacramento State. He had a buzz cut, sharp-boned features and two felonies on his record. Seven months earlier, police had found him with a stolen sawed-off shotgun; four months after that, with bullets and brass knuckles.

He was worried about a third strike. Before getting into the car, he had stuffed his bloody clothes into a bag and washed his knife.

They rolled along the western edge of the Central Valley and headed north through the last of the night and into the morning.

When the phone rang that morning at their home in Concord, a San Francisco suburb, Fred and Kathy Santos were just awakening to their weekend. They had met as undergraduates at Oregon State University and been married for 28 years. He was a tech troubleshooter at an online car-auction company. She oversaw maintenance at a UC Berkeley math building.

They were empty nesters. Their 23-year-old daughter, Brigida, bookish and reserved, had just graduated from college and was working in Los Angeles. Luis was attending a junior college in San Diego.

Luis looked like his sister’s twin but was her opposite in most ways. He was flamboyantly social, a kid who “always came off a plane knowing the life story of the person he sat next to,” his mother would say.

He was a collector of friends, who would rather be anywhere than alone, except maybe in a classroom. He liked beer pong, Bob Marley and the HBO series “Entourage.” He did a Mr. Bean impression and had memorized the punchlines in “The 40-Year-Old Virgin.”

He was the kind of student that teachers called smart but unfocused. After high school he applied to cooking school, dropped the idea, tried a two-year college in Woodland Hills, dropped out and finally decided to follow a childhood buddy to San Diego, where the party atmosphere suited him.

He was taking business classes at Mesa College and living on supermarket-deli sandwiches he bought with gift cards from his mother. He wore high-top sneakers everywhere and refused to show his legs, which were as skinny as the rest of him, though he lifted weights and guzzled whey-protein shakes.

He had olive skin, close-cropped hair and a struggling goatee. Girls told him they loved the long lashes curling over his hazel eyes. He didn’t have a girlfriend. “He’s like, ‘Girlfriends are expensive,’ ” his sister recalled. “I think he knew girls wouldn’t take him seriously if he didn’t have his life together. He didn’t seem in any hurry.”

His parents expected him home in Concord for Thanksgiving in a few weeks. He still had an upstairs bedroom covered with race-car pennants and football posters.

The phone rang. It was Luis’ childhood friend Navid Sabahi. He sounded scared. He’d heard there was a fight. Someone had been stabbed. He thought it might be Luis.

Fred Santos, is a reserved, cerebral man who prides himself on his unflappability, and now he went to work searching the Internet for the phone numbers of San Diego hospitals. He called the ERs. He called the San Diego police. They had arranged for Concord officers to drive to the Santos home and deliver the news in person.

Before they could, Fred reached a San Diego sergeant, who told him his son had been killed.

Are you sure it was Luis?

Yes.

How?

His wallet was on him.

Maybe he dropped his wallet.

It is a positive ID. His friends were with him, the sergeant said.

He added, “They were jumped.”

Luis Santos had been hanging out with Scheerer on the steps in front of Cox Arena, a basketball and concert venue near Fraternity Row at San Diego State.

Santos and Scheerer had been partying in the area; both had been drinking hard. By Scheerer’s account, the trouble began when a group of four young men appeared on 55th Street in front of the arena and began taunting them.

They looked like they were from out of town; they did not have the flip-flops-and-board-shorts look of San Diego college kids.

“They made a beeline for us,” Scheerer would recall. “They said, ‘What do you have? We have knives.’ They threw up their hands like they wanted to fight.”

Scheerer said the strangers pursued them, blocking their path. He heard someone say, “Why don’t you fight? This is how Sac-town does it.”

Scheerer, stouter and two years older than Santos, tried to shield his friend from the group as they walked away. He thought of him as a skinny kid brother who wouldn’t be much good in a fight.

After a while, the strangers seemed to grow bored and drifted down the street. On his cellphone, Santos tried to get through to his buddy Keith Robertson, who was with two other friends at the trolley station on campus.

Santos dialed Robertson at 2:10 a.m., 2:11 a.m. and 2:12 a.m., and got through on the third try. Santos sounded scared. We’re about to be attacked. Come quick!

The friends came running and met Santos running the opposite way. One of the last things he said was: “They’ve got knives.”

There were security cameras outside the arena, the gym and a police station on 55th Street, but the brawl unfolded in the cameras’ blind spots. The blurry video did not reveal when the knives came out or who stabbed whom.

What is certain is that one of the knives pierced the cartilage between Santos’ fifth and sixth ribs, sliced his left lung and cut the left ventricle of his heart. Within seconds, one group was heading toward a waiting car, while the other was in the street, cut and bleeding.

At 5:29 p.m. that day, a surveillance camera captured Nuñez, Jett and Garcia at a 7-Eleven near Nuñez’s Sacramento apartment. Jett left the store with an empty Big Gulp cup. He carried it back to the car with $1.30 worth of gasoline from the Union 76 station next door.

News of the stabbing had been online since that morning, and they were determined to sever their ties to the crime. They drove a little ways and parked near Interstate 5 along the Sacramento River. They got out and climbed down to the water. It is a broad river, the banks thick with foliage, its shores sometimes populated by transients.

Jett carried the clothes he and Nuñez had worn in the fight. He dumped them in a pile, doused them with gas and set them ablaze. He said he watched Nuñez throw the knives in the river.

The clothes burned; the knives sank; the friends would keep quiet. What could link them to a stabbing 500 miles away?

Detectives made the connection within hours.

A young woman had approached them at the crime scene, hoping to help. Her cellphone held text messages from a friend named John Murray. He’d had to leave town fast, he wrote to her, because his buddies had been in a stabbing.

Reluctantly, Murray, 19, told detectives what he knew. He admitted that he’d partied with the Nuñez group that night, then drank himself to sleep, missed the fight and joined the group for the hasty car ride north. He had been at the river during the destruction of the evidence, and said he’d overheard Nuñez and Jett agree not to speak of this again. It would be a secret among friends.

Another tip came from Brianna Perez, 19, a cousin of Nuñez’s friend Rafael Garcia. The Nuñez group had stopped by her apartment near Fraternity Row before the stabbing. They had backpacks full of beer and a large bottle of Captain Morgan rum.

They were angry that they had been rebuffed when they tried to get into a frat party earlier, she said. They were cursing the frat boys. Some of them used knives to open their beer cans. She remembered some of them talking about burning down the frat house, about finding a fight.

“They were going to show them how they did it in Sac-town,” she would say. When they left her apartment, she worried that they were looking for “drama.”

On Oct. 8, 2008, four days after the killing, a team of plainclothes San Diego detectives strode up a broad stone walkway toward a house on American River Drive in one of Sacramento’s nicest neighborhoods.

The man who answered the door was one of the capital’s most recognizable faces. Fabian Nuñez was at the tag end of a storied legislative career. That year, he’d surrendered the role of Assembly speaker, a job he had secured as a 37-year-old freshman legislator and held for four years. With the confidence of a lifelong scrapper, he had become the most powerful speaker in California’s term-limits era.

He had married his college sweetheart, divorced her, then remarried her. Along the way, they had a daughter and two sons. Many expected him to run for state treasurer or mayor of Los Angeles.

Nine months earlier, as national co-chairman of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s presidential campaign, he had introduced Clinton to a crowd of thousands at Cox Arena, yards from where Santos was killed.

Today, homicide detectives greeted him with a warrant. They wanted to search the house and take his son’s DNA.

The elder Nuñez said he had already spoken to a lawyer. “I was aware something had taken place down in San Diego, but I didn’t know you guys were coming here,” he said, according to a police report.

He led detectives to his son, who was at Sacramento City College, and waited outside the police station while evidence technicians did their work.

The younger Nuñez peeled off his shirt to be photographed. They looked for cuts or bruises from the fight, and found none. Tattooed across his muscular back, in spiky Spanish script, were words that translated as “Better to Die on Your Feet Than Live on Your Knees.” It was a phrase from Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican revolutionary his father liked to tell him stories about.

A detective tried to get him to talk.

“I can give you the number of my lawyer,” he said.

Detectives had better luck with Leshanor Thomas, Nuñez’s former college roommate. He sat in a 10-by-10-foot interrogation room and acknowledged that he had participated in the deadly brawl, and that he and his friends had fled the scene.

“You don’t know what other people have told us,” a San Diego detective told him, “so it’s kind of like your best interest to tell the truth.”

The detectives thought he was holding back. One said, “This is huge.”

“I know that,” Thomas said.

“Huge.”

“I know it’s huge,” Thomas said. “I thought they was my friends but then I, like, just, somebody has to take the fall for it, and I’m not gonna be it.”

“This is murder,” the detective said. “Some kid lost his life.”

“Yeah. I know that,” Thomas said. “And some parents don’t have a son.”

The detectives asked if he was scared.

“To be honest, my safety, just me knowing what happened and me being pulled in is putting my safety at risk,” he said.

He said that Jett had initiated the fight, rushing across 55th Street to confront the other group, and Nuñez followed, then Garcia, then himself. He’d thought it was just a fistfight and had seen none of his friends with weapons, he said, though he wouldn’t be surprised if Nuñez had carried a knife that night.

“I do remember from when I stayed with Esteban, he always had some type of new knife,” he said. “Some type of new little handy-dandy knife, whatever.”

A detective asked whether any of his friends had bragged about the stabbing.

“It would have to be Esteban,” he replied. “Esteban said, ‘Yeah, I got one of them.’ ”

He recalled something else Nuñez had said.

“Hopefully, my dad could take care of this.”

Did Thomas know who the dad was? He said he did not.

“Big,” the first detective said.

“How big?” Thomas asked.

“Big.”

The other detective clarified: “Capitol big.”

Thomas said, “Dang.”

For Fred Santos, the days after his son’s death were a blur. He wouldn’t remember where his meals came from or how he got from one place to another. He couldn’t name the day of the week.

“That’s not something you prepare yourself for — your kid being murdered out of the blue,” he would say. “My body and brain couldn’t deal with it.” To cope, he gave himself projects: Find a funeral home. Buy a cemetery plot. Choose a casket. Pick passages of Scripture.

Hundreds of people gathered for the service. Many wore high-top sneakers, because they all remembered Luis wearing his. Fred sang an Eric Clapton song, “Tears in Heaven,” about losing a child, and put his own high-tops in his son’s casket.

Luis’ sister, Brigida, remembered how he would appear in her bedroom as a little boy, afraid of the dark, begging to sleep on her floor. And the way he voiced action-movie explosions when he drove, pretending to blow up the traffic. And the time he tried to jump across the duck pond near their house, showing off for friends, and came up smeared with algae.

His parents learned something surprising about their son, something he had told his sister and friends but had never told them: He didn’t expect to live into his 30s.

It was possible that this anxiety stemmed from a protracted illness that forced him to miss fourth grade. He had an enlarged colon and was on a feeding tube for six months. Knowing that the smell of food tormented him, his parents ate their meals in the car.

His mother remembered it as a magical period of nearly unbroken time with her son. She read him library books about volcanoes and stars, and they took field trips. And then he got better and refused forever after to tell his parents when he had a stomachache. He seemed to dread nothing more than a return to the hospital. Maybe it helped explain his freewheeling approach to life.

He would call his parents all the time, just to chat. His mother looked at the phone bill and noticed that their last conversation had been 18 minutes long. She wondered how many families had that kind of luck.

Around the time of the funeral, San Diego police called to say they knew who had killed Luis. They were building a case. All of October passed, and all of November.

Fred and Kathy returned to work. “You don’t have to tiptoe around me,” he told co-workers. “I’m fragile, but I’m OK. If you see me crying, that’s OK.” Grief struck most vividly as he drove home from work. That had been when he and Luis would talk on the phone, about the Giants and the Raiders and the Golden State Warriors.

Fred couldn’t follow sports any more. He stopped watching his favorite TV dramas like “CSI” and other crime procedurals. So many involved parents burying children.

His wife gathered her co-workers at UC Berkeley and told them to let her grieve privately. “Please don’t show me any sympathy,” she said. “Please don’t ask me any questions.” She distanced herself from friends in the break room. It hurt when they talked about their families.

She kept returning to her son’s upstairs bedroom. She had kept it unchanged while he was away at college, and she did not intend to alter it now. She picked up his cologne, Acqua Di Gio, a birthday present from her, with which he had splashed himself liberally. She sprayed it into the empty room.

In the conference room of the district attorney’s office in downtown San Diego, the prosecutor listened as a team of detectives walked through the case, witness by witness.

Jill DiCarlo was a career prosecutor, a cop’s wife with a relentless work ethic. She would be able to navigate what everyone knew would be a media-saturated case. Now, she had to decide whether there was enough evidence to charge the suspects. After the presentation, she thanked the detectives and took the binders of evidence back to her office.

Studying the witness statements, she found one from a young man — a stranger to Santos — who had been hanging out on the steps of Cox Arena just before the attack. The witness said an inebriated Santos had claimed he was in a gang and carried a Glock 40 for protection, but it had just seemed like “drunk talk.”

Another young man on the steps said Santos spoke of having been beaten up in Tijuana, and boasted that since then he had carried a “thang.” He’d gestured toward his waistband.

No weapon had been found on Santos, and none of his friends recalled ever seeing him with a gun. There was no suggestion he’d been looking for a fight that night.

But Nuñez seemed to relish confrontation, the prosecutor thought.

On his seized laptop, in a trove of his rap lyrics, he touted the Hazard Crew, or THC, as family. He espoused the importance of loyalty, and promised violent death to those who disrespected his crew:

“we all family ya c if u f— wid my boys ill go on a killing spree.”

He wrote paeans to stealing and evading the law, painting himself as an outlaw who humiliated enemies, menaced them with a “shotty” — a shotgun — and killed them gruesomely with knives.

“never played or betrayed, always quick to grab the blade.”

Considering the circumstances of Santos’ death, some of the lyrics struck the prosecutor as eerily prescient.

“ill deliver that knife throu ur liver let u bleed to death while ya shiver…. My crew will swarm u like some locus…. I alredy explained how I stress ill make a mess when opening ur chest.”

DiCarlo would learn that the Sacramento Police Department did not regard THC as a gang worthy of the name. “A wannabe gang,” she thought. But it seemed to loom large in Nuñez’s identity.

“thc is a community of unity … I cnt b touched call it immunity … It ain’t nothing to me but a sport … I aint scared of court … but my lawyer is my last resort … dnt get caught no police report.”

To her mind, the lyrics helped explain what had happened the night of the stabbing. Banned from the frat party, Nuñez’s crew had been disrespected and humiliated, and they wanted payback.

Studying Nuñez’s text messages, she got a glimpse of his mind as police were closing in. Four days after the stabbing, he had sent one to Garcia: “Gangster rap made us do it lol.”

Around the same time, Nuñez sent repeated messages to Leshanor Thomas, telling him not to talk: “just dnt say ne thing u have the right to an attorney to be present so that’s all u gotta tel cops.”

She studied the transcript of Thomas’ interrogation, and was struck by something he had recalled Nuñez saying: “Hopefully, my dad could take care of this.”

At least once before, facing trouble from the law, Nuñez had sought refuge under his father’s wing.

Late one night in March 2008, seven months before the stabbing, a patrolman at Cal State Los Angeles stopped Nuñez in his mother’s white BMW near campus. There had been reports of computers stolen from the dorms, and the officer had seen three men climb into the car carrying large bags. Looking into the back seat, he saw a bag containing what looked like electronic equipment.

“What’s inside the bag?” he asked Nuñez.

According to the police report, Nuñez said it was a stereo that a friend had given him to throw away. The officer asked more questions. Nuñez grew argumentative and invoked his family connections: “Do you know who my dad is? He is Fabian Nuñez. He’s an assemblyman in Sacramento. I am going to call my dad.”

Nuñez called his father and handed the cellphone to the officer.

The report does not record what the Assembly speaker said. Nuñez says he told the officer, “If my son did something wrong, he should pay for it.”

The case was classified as “suspended due to lack of solvability factors.”

Three months later, as they cleaned out Nuñez’s vacated dorm room during the summer break, a Cal State L.A. crew found an empty box for a Mossberg shotgun, according to a police report.

It was against the law to bring a shotgun to school, but police could not prove that he had.

Now, studying everything detectives had learned about the San Diego State stabbing, DiCarlo tried to understand the dynamics at play among the attackers. Nuñez seemed to be the glue, the one who brought them all together.

In the chaos of the fight, no one could positively identify who had stabbed whom, and the surveillance footage did not help. But DiCarlo was confident the law was on her side. She did not need to prove who did the stabbing. All four men in Nuñez’s group had acted together in encouraging the attack, as she saw it, and all would be considered principals under the aider-and-abettor law.

“In a group fight, it’s almost impossible to ascertain who did it,” she says. “That’s why the law treats them exactly the same.”

The charge would be murder.

On Dec. 2, 2008, police arrested Nuñez and Jett in Sacramento and put them in the back seat of a squad car hoping to secretly record an incriminating exchange. The tactic failed.

“Pretty sure this is wired,” Jett said.

The two men talked about the price of gas, the pretty girls at 24 Hour Fitness, a teriyaki restaurant and how much they dreaded the 500-mile drive to San Diego, where they would be arraigned.

“Tell me why I was watching ‘Law & Order’ before I left?” Nuñez said.

“I don’t watch shows like that,” Jett replied.

“I do, so I can beat the system,” Nuñez said, and laughed.

The weight of the elder Nuñez’s influence was felt almost immediately, as letters inundated San Diego County Superior Court pleading for a reduction in his son’s $2-million bail.

Among the authors was Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a longtime friend of Nuñez and past beneficiary of his political influence. In the Legislature, Nuñez had fought to give the mayor something he prized: greater control of city schools.

Now, the mayor wrote that he had known the son for more than 10 years.

“In my heart, I know Esteban Nuñez as a young man of good and upright character,” the mayor wrote on official letterhead, as though speaking for the nation’s second-largest city itself.

State Assemblyman Kevin de León, who had known the Nuñez family for decades, used his legislative stationery to describe the accused as “considerate, gentle and well-mannered.”

Another letter came, on official stationery, from Assembly Republican Leader Michael Villines, describing the Nuñezes as a “loving and close” family.

Another came, on union stationery, from Maria Elena Durazo, head of the L.A. County Federation of Labor, describing the younger Nuñez as “warm and gracious.”

A judge cut Nuñez’s bail to $1 million, and after eight days in lockup he was home with his parents. Garcia, the son of a judge, also posted bail. Like Nuñez, he was now represented by a top-notch private defense attorney. Thomas and Jett, who couldn’t raise bail, got public defenders and stayed behind bars.

As the months passed, prosecutors tightened their focus on winning convictions against the two defendants they believed had wielded knives: Nuñez and Jett. Thomas and Garcia struck deals that would ultimately get them probation; in exchange, they would have to take the stand against their friends.

Garcia’s story was damning: He said that Nuñez had taunted the unarmed Santos group, and had rushed into the fight with his knife drawn.

He said that after the stabbing, Nuñez had bragged, “I got one of ’em,” and that Nuñez, having stuffed his clothes into a bag, had said: “We’re just gonna go to the river right quick and burn it.”

“We don’t have to worry,” he recalled Nuñez saying. “How would they find us? There’s no way they could connect it to us.”

Fred and Kathy Santos were vaguely familiar with the Nuñez name; the assemblyman had been in the news for years. But they knew little else about him.

Back in Macau, where Fred spent his first 18 years, it was easy to spot the Tai-Pans. They were the men in the back seats of the long, chauffeured cars that drove slowly over the island’s narrow cobblestone streets, heading to favorite restaurants.

They seemed mostly benign, these men. But few doubted what would happen if they were ever confronted with the law. The law, not the Big Men, would give.

Fred had learned the cadences of American English by watching “The Bob Newhart Show” on an aunt’s black-and-white TV. His father was a bank clerk. His family spent its savings — and relied on gifts from friends — to send him to the United States for college. He was the first in his family to attend.

He wondered how the case against his son’s attackers might unfold in Macau. He thought he knew. Someone connected to his extended family — probably a friend — would try to find and kill the culprits. Maybe he would be told the details; maybe not.

In America, you forswore vengeance and put your trust in the justice system.

The Nuñez family had money and vast connections. But on his family’s side was the work of experienced detectives, a tough-minded prosecutor and the rule of law. Surely no amount of money or influence could trump all of that.

Part 2

On the eve of a murder trial, a deal is struck. But will it stick?

The fathers had been advised not to exchange words, or stand too close to one another. If Fred Santos walked left, Fabian Nuñez walked right. If they happened to pass in the hallway, they tried not to meet each other’s eyes.

During their many trips to the Hall of Justice in downtown San Diego — for the preliminary hearing, the motions, the arguments over evidence — they became accustomed to this dance of avoidance.

Santos’ 22-year-old son, Luis, had been stabbed in the heart in a brawl at San Diego State University. Nuñez’s 21-year-old son, Esteban, faced life in prison for the killing. In the law’s citadel, it was supposed to be irrelevant that one father was a tech troubleshooter for a car auctioneer, while the other had been California’s most powerful lawmaker.

—

The murder trial was expected to be a long one, maybe lasting months. Santos and his wife, Kathy, had packed their suitcases, flown to San Diego and put down the first month’s rent on a house. They were determined to attend every day of testimony, however excruciating.

The jury was being chosen and opening statements were just days away when San Diego’s elected district attorney, Bonnie Dumanis, summoned the trial prosecutors to her office to discuss a plea bargain. The defense had been asking to deal.

Dumanis was willing to drop the murder charges against Esteban Nuñez and his codefendant, Ryan Jett, if they would plead guilty to manslaughter. If they agreed, they would serve 16 years each at most.

Rick Clabby, the second-chair prosecutor, thought it was a terrible deal, a view he would learn was widely shared in the office.

“Listen, the Santos family doesn’t want this — they want us to go to trial,” he told Dumanis.

Clabby insisted they had the evidence to convict on murder. They had worked for nearly two years to bring the case to trial. Why settle now? Why settle for this?

The D.A.’s office did not need the approval of the victim’s parents to make the deal. But it would be awkward if Fred and Kathy Santos opposed it publicly.

Called to a meeting with the district attorney, they listened as prosecutors explained the terms.

Since Nuñez was arrested in late 2008, the parents had been unable to shake the suspicion that politics might influence the course of the case. Nuñez’s father, Fabian, a Democrat from Los Angeles, had served three terms in the California Assembly, two as speaker, and now worked at an influential lobbying and public relations firm. His relationships spanned the worlds of business, politics and labor, and in all three his advice — and, even more, his support — was prized.

So Fred Santos, long past the point where he thought such questions might be rude, asked Dumanis her party affiliation. She was a Republican. This was a relief to him.

Did she have plans to run for the state Assembly? No. Did she want to be governor? No.

He did not ask whether Dumanis had other ambitions. She did. She wanted to be mayor of San Diego, a bid she would make official 10 months later, running — unsuccessfully — on a claimed 94% conviction rate for the D.A.’s office.

The plea bargain had advantages for Dumanis, if cold political calculus was the measure: It guaranteed convictions in a high-profile case and sidestepped the risk of an embarrassing loss.

Santos had another question: Could the defendants make this deal, and later try to undo it on appeal? Highly unlikely.

The parents found a private room and called their daughter, Brigida, 25. After her brother’s death, she had suffered from blackouts, violent stomach cramps and vomiting attacks. She had believed she was dying. She remained inconsolable, too distressed to attend the trial.

Now her parents explained the terms of the deal. They knew the toll the case had already taken on her. Even if jurors convicted, there would be endless appeals. A plea deal meant finality.

They agreed to accept it.

Dumanis gave her prosecutors the order: Make the offer.

—

Superior Court Judge Robert O’Neill was a Republican who jokingly described himself as “to the right of Attila the Hun.” He’d been a military policeman, a motorcycle cop, a prosecutor, a defense attorney.

Now in his 60s, he wore a bushy white mustache and liked to quote the Founding Fathers from the bench. He limped into his courtroom in an orthopedic shoe, a reminder of a drunk driver who had ended his police career.

When the defendants appeared before him on May 4, 2010, he took pains to make sure they understood the stakes. If they accepted the plea bargain, there was no certainty as to the sentence he would impose — he would have to study the facts, weighing aggravating and mitigating factors.

“You won’t do more than 16 years and you may do less,” O’Neill told Nuñez and Jett, adding: “So if you want to ask me, ‘What am I going to get on sentencing date if I took that offer?’ I can’t tell you that. And the reason why is I don’t have all of the information.”

Luis Santos had been killed in a clash between two groups of young men — one armed, one not — near San Diego State’s Fraternity Row on Oct. 4, 2008. From the dim, blurry surveillance video, it was impossible to tell who had delivered the fatal blow. The prosecution’s theory was that Jett had stabbed Santos; this was based largely on the account of a witness who saw him throw a roundhouse swing at a dark-complexioned young man.

Nuñez had also wielded a knife. As best as investigators could determine, he had stabbed two of Santos’ friends, one in the stomach and back, the other in the shoulder.

Both defendants were charged with all three stabbings because they were deemed to have acted together.

If they went to trial, the judge explained, they were gambling. A first-degree-murder conviction meant 25 years to life; second-degree murder was 15 to life. Even if jurors decided it wasn’t murder, there were other charges that together could bring more than 16 years.

“Add it up. I mean, you have a tremendous exposure there,” O’Neill said. “So the bottom-line question to it is, ‘How lucky do you feel today?’”

He stressed the ironclad finality of the plea. “With a plea bargain, there is certainty. That’s the deal. It is a deal. It is a contract. You take the offer. That’s an acceptance. That’s a contract. That’s enforceable.”

The defendants were back in court the next day. They had decided to take the deal. Jett went first, pleading guilty to voluntary manslaughter in Santos’ death, and to assault with a deadly weapon in the nonfatal stabbings of the victim’s two friends.

Then came Nuñez’s turn. The judge held a three-page change of plea form. It had been signed and initialed by Nuñez, and marked with his thumbprint, to formalize his plea of guilty to manslaughter and assault.

“The maximum penalty could be 16 years in state prison, $20,000 fine, restitution. Do you understand that?” the judge asked.

“Yes, your honor,” Nuñez said.

The judge recited the elements of the crimes for which Nuñez was taking responsibility, and asked him to affirm his guilt. He used the victim’s formal Portuguese surname.

“‘I intentionally committed an act that caused the death of Luis Dos Santos and/or aided and abetted in the unlawful killing of Luis Dos Santos.’ Is that a true statement?”

“Yes, sir.”

“‘The natural consequences of the act were dangerous to human life.’ Is that a true statement?”

“Yes, sir.”

“‘At the time I acted, I knew the act was dangerous to human life.’ Is that a true statement?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“‘I deliberately acted with conscious disregard for human life.’ Is that a true statement?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“‘I also admit to personally using a knife in the unlawful killing of Luis Dos Santos.’ Is that a true statement?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“You are convicted,” the judge said, and ordered the defendants — both of whom had been free on bail — back into custody.

—

As the sentencing date approached, Nuñez wrote a letter to the judge:

“I am not proud of what has happened. I live with remorse. What happened is terrible and I am in no way trying to justify my actions. I am merely attempting to expose the truth….

“I can’t imagine the struggle the Dos Santos family goes through daily. I pray for them every night, for their son will never come back and it is terrible….

“I’ve made many mistakes in my past but I assure you I’m not a bad person. The people who know me know the loving and gentle heart that is in me. I have learned many things going through this case and I have grown tremendously. I have reevaluated the people I place around me for they had negative influences on me….

“Sadly, I can’t change the past. I can only evaluate and learn from it so the same mistake won’t be made twice, and I intend to continue doing so. But I don’t believe sending me to prison would help me in any way surround myself with positive influences….

“I want you to know I’ve always intended to take responsibility for my actions. Yet, the D.A. was never interested. I was willing to turn myself in as soon as an arrest was issued, yet they had different plans….

“But, that is not my concern. My concern lies in a thorough observation of the facts and circumstances surrounding the case. It is my profound hope that you also take in consideration that I have no criminal history….”

—

“We have cried until our faces burned,” Kathy Santos said.

It was sentencing day, June 25, 2010. The victim’s mother stood facing the judge and spoke of her son. Luis, a student at Mesa College in San Diego, had been exuberantly social, if unfocused about school, and devoted to his family.

The mother glared at the defendants. “Demons,” she called them, and added: “I pray that the universe will deliver to you a just punishment for your empty and satanic souls.”

She had contempt for them and their attorneys, she said, “for being evil, and for defending evil.” She pleaded with the judge. “Please don’t allow their political connections and influence to cheat our family and Luis.”

It was time for Fred Santos to speak. He stepped to the lectern, and drew a breath.

“They got away with murder,” he said. “This is not closure. There will never be closure. This is just an end to the criminal proceeding, to the agony of sitting in court.”

He held up an enlarged photograph of his son’s gravestone. “This is all we have left,” he said. “We go to his marker and pretend he can hear what we are saying.”

Ryan Jett would be sentenced first. He faced the Santos family and begged for forgiveness. The judge noted that Jett had prior felony convictions for weapons possession and had been on probation. He gave him 16 years.

It was Nuñez’s chance to say he was sorry, if he wished. He did not. Instead, defense attorney Brad Patton tried to diminish his client’s share of the blame.

He argued that Santos had sparked the fight with a drunken remark: “I got my thang on me,” an apparent reference to a gun, although Santos was not carrying one. Patton contended that after the confrontation subsided, Santos had reignited it by summoning his friends on his cellphone.

Jett had attacked Santos in an act of “terrible, horrible spontaneity,” and Nuñez had used his knife only after he saw Jett had been tackled and needed help, the defense lawyer said.

Prosecutor Jill DiCarlo responded: Santos was unarmed, a threat to no one. He had called for backup out of fear. “It is the people’s position that Mr. Nuñez did not inflict the fatal stab wound … but it’s as good as if he did,” she said. “He aided and abetted that fatal blow, and he is just as guilty.”

She invoked Nuñez’s letter to the judge. Nuñez spoke of wanting to “expose the truth.” But he offered no apology, showed no remorse and took no responsibility, the prosecutor said.

“If now he wants to come before this court and say, ‘I really want the truth to come out,’ then he should have taken this case to trial,” she said.

She cited Nuñez’s remark to a probation officer — who was preparing a sentencing report — that he carried a knife “because there had been many threats made to his family, but he never intended to go out and hurt somebody.”

“So are we to believe, and Mr. Nuñez is to have this court believe, that college students at San Diego State University are a threat to his family?” DiCarlo asked.

Now Judge O’Neill spoke. He said that each defendant “is treated separately and distinctly by the court,” so he would weigh Nuñez’s aggravating factors and mitigating factors separately from Jett’s.

The judge noted that Nuñez had no previous criminal record — a point in his favor. He considered Nuñez’s claim that he pulled his knife to defend his friend. That gave the judge pause. Then why had he fled home to Sacramento and thrown his knife into a river?

He noted that Nuñez had already “benefited considerably by the plea agreement.” To impose the maximum term, the judge explained, he needed to find just one aggravating factor. He found several.

Did the crime reflect great violence, cruelty or callousness? Yes, the judge ruled. Nuñez had stabbed Santos’ two friends “but did absolutely nothing to help.”

The judge said, “Defendant Nuñez did everything he could to destroy evidence and try and distance himself from these crimes. Actions after the fact, even knowing that Mr. Dos Santos was deceased, I believe, show callousness, a disregard for human life, and are evil.”

Did Nuñez occupy a position of leadership in the group? Yes, the judge ruled. Did the crime indicate planning? Yes. He had brought a knife to a college campus.

“Being stabbed by a knife is personal,” the judge said. “A knife in someone’s hand being plunged into your body — that is in your face, and that is personal.”

For the manslaughter charge, the judge imposed 11 years, plus a year because it was done with a knife, plus four years for the two nonfatal stabbings.

Sixteen years.

The defendant began to cry.

—

Fred and Kathy Santos left the courtroom relieved that it had been settled — not perfectly, but finally. Fred tried to lose himself in his work, putting in 60- and 70-hour weeks. Sometimes he carried his guitar into his son’s upstairs bedroom, which was still untouched, and sang for him among the Golden State Warriors pennants.

He couldn’t watch football or basketball anymore. Seasons sailed by, championships were clinched, and Fred missed it completely. Among strangers, he learned to dodge the question about whether he had children.

Fear of that question, he knew, had made his wife — once ebulliently social — avoid dinner parties. What should she say? Two kids? That wasn’t true anymore. One? That seemed to negate Luis’ existence. She could say, “One was murdered,” and watch silence fall over the room.

—

The plea deal was supposed to mean certainty. Yet only five weeks after the sentencing — it was now August 2010 — defense attorney Brad Patton was standing before the judge, making an admittedly awkward request.

Patton had told his client he could expect a lighter sentence. He said he had based this on O’Neill’s remark in court — and on his unrecorded remarks in chambers with lawyers from both sides — that he would treat Nuñez differently from Jett.

In Patton’s view, this meant less time for Nuñez, who had no previous record and had supposedly not inflicted the fatal wound. If Jett got the maximum term of 16 years, shouldn’t Nuñez get the middle term of six?

“I can tell the court definitively that, had they known that this was going to be a 16-year case for Esteban, this plea would not have gone down,” Patton said.

“What you told the family, and the expectation of the family — I really have no control over that,” the judge replied. It was not entirely certain who had stabbed Santos, he added. “There is some argument to that particular contention.” Had the case gone to trial, Jett’s lawyer was prepared to argue that it was Nuñez.

In his previous on-the-record remarks in court, the judge had vowed to weigh the two defendants’ punishments “separately and distinctly” but had never promised a lighter term for Nuñez.

As the argument wore on through multiple hearings, DiCarlo reminded the judge that he had repeatedly warned Nuñez he could get as much as 16 years.

“The bottom line here is Mr. Nuñez does not like the sentence he got, so at first he blames the court, and now he is blaming his defense attorney, and unfortunately Mr. Patton is falling on his sword.”

At a September hearing, the judge reaffirmed his sentence. “An aider and abettor is punished under the same sentencing schemes as the principal,” he said. “I have given this a great deal of thought, and I see no basis either in law or in fact where the court could properly exercise its discretion and resentence Mr. Nuñez.”

“I can assure you —” the judge continued.

“But, sir,” a voice interrupted from the audience. It was Fabian Nuñez, on his feet.

“You said you would treat my son differently than Mr. Jett in this court. You said that you would treat them differently.”

“Mr. Nuñez, sir, that is correct, and I did,” the judge replied. “Just so the record is clear, if you review the transcripts, there is nowhere in the transcripts that I indicated that I would sentence Mr. Nuñez to a term of six years, and that’s the contention. I did not say anywhere in any transcript —”

Nuñez cut him off again. “You did, sir. You said it in this courtroom.”

“If you can show me somewhere in the transcript I said that, I stand corrected,” O’Neill said.

It was dangerous to challenge a judge in his own courtroom. It is not clear how long O’Neill would have tolerated it. But within moments, the former Assembly speaker was heading briskly for the door.

Another Nuñez attorney, Charles Sevilla, told the judge he had checked the record and found that O’Neill had not, in fact, promised a specific sentence.

Fred Santos had watched Nuñez’s outburst with dismay. It seemed to confirm his sense that Nuñez thought himself above the rules that applied to everyone else.

Now Santos addressed the judge: “Since the family of the defendant has a right to speak, I would like —”

Prosecutors motioned for the victim’s father to be quiet. He obeyed.

—

Soon after Esteban Nuñez moved into his cell at Mule Creek State Prison in Ione, Calif., one of the warden’s assistants arrived at work to find a package waiting on her desk.

The assistant was a liaison to inmates’ families. After four years in the job, she’d gotten many thank you notes but never a gift.

The package was a Kindle, courtesy of Fabian Nuñez.

She promptly sent it back.

—

From early on, the Santos family had worried about the reach of Fabian Nuñez’s power. He had been the state’s most powerful Democrat, so they believed his pull would be strongest among Democrats. They had missed that his most powerful friend was the Republican governor.

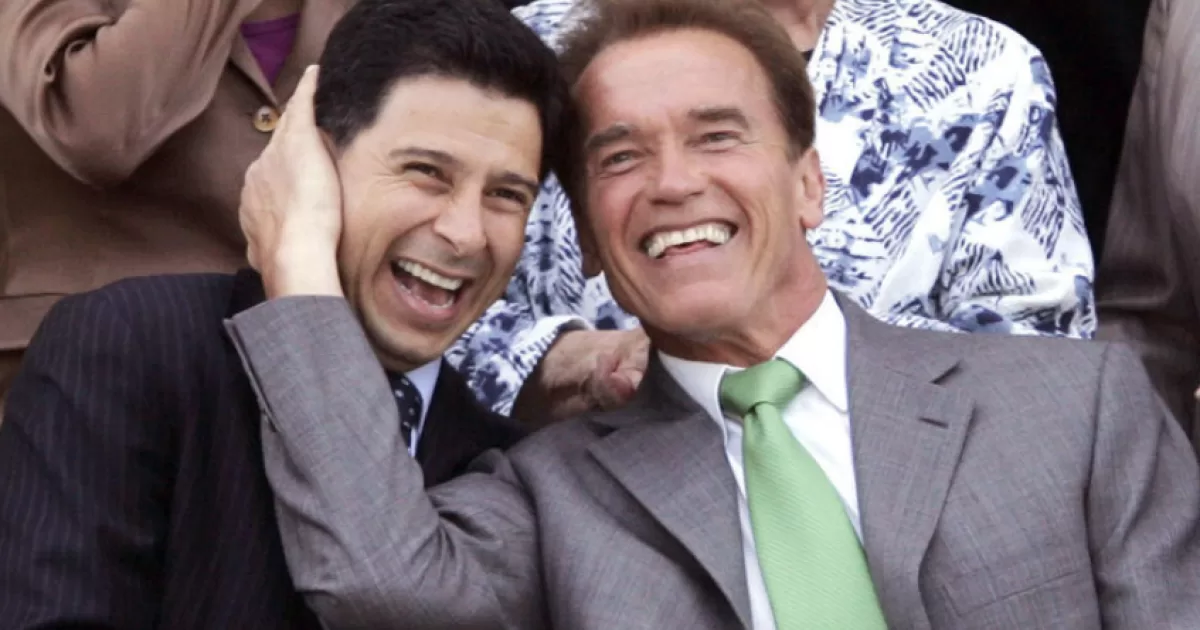

Arnold Schwarzenegger and Nuñez had started out as adversaries. Schwarzenegger derided Democrats as “girlie men,” Nuñez as a “punk.” Nuñez accused the governor of wearing shoe lifts and makeup, and in 2005 helped crush his four special-election initiatives, including measures to curb union campaign spending and redraw election maps.

Improbably, around that time, a working amity blossomed. A battered and conciliatory Schwarzenegger perceived the value of the Assembly speaker’s sway over fellow Democrats in a deep-blue state. The governor invited the speaker for cigars and schnapps in his outdoor smoking tent, gave him rides on his private jet and hosted him on the patio of his Brentwood home.

Nuñez took Schwarzenegger out for Mexican food at La Serenata de Garibaldi in Boyle Heights. They greeted each other with hugs, and in photographs they seemed giddy in each other’s company.

It was easy to dismiss this as a friendship of convenience, but their biographies hinted at the basis of a deeper bond. Both were flamboyant and ambitious men who dressed to the nines, born outsiders who had fought their way to the apex of power in the nation’s most populous state.

Schwarzenegger was possibly the nation’s most famous immigrant — the Austrian Oak, Mr. Olympia, Conan the Barbarian, the action hero, fitness czar, Kennedy in-law and now the Governator. Central to his story, as to Nuñez’s, was his image as a beneficiary — and an exemplar — of the American dream.

“California is once again, my friends, on the move, thanks largely to this next man, the governor of our great state and a good friend of mine, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger,” Nuñez said in introducing him on the occasion of the Mexican president’s visit to Sacramento in May 2006.

The effusiveness of the praise was striking, considering that Nuñez was co-chairing the campaign of the Democrat trying to win Schwarzenegger’s job in the upcoming election.

“Well, thank you very much, Fabian, for the wonderful introduction, and for the wonderful things you said,” the governor said. “This is really great stuff that I can use to get reelected.”

In that cause, Nuñez offered more than glowing blurbs. He and Schwarzenegger united in a push to raise the minimum wage, cap greenhouse-gas emissions and put a $42-billion public works bond package on the ballot, marginalizing Democratic challenger Phil Angelides. That November, Schwarzenegger won a second term handily.

—

Sunday, Jan. 2, 2011

In the Capitol, it was gray and cold on the last day of Schwarzenegger’s seven-year governorship. His offices had been emptied, the famous smoking tent dismantled. He had gathered his exhausted staff for a final goodbye, and left town to resume his Hollywood career.

There was talk of another “Terminator” sequel. There was talk of a cartoon series, “The Governator,” in which Schwarzenegger would play himself as a “devoted family man” and crime-fighting superhero.

There was no drama surrounding his announcement that afternoon, no news conference. There was just an emailed news release from his office at 4:13 p.m., and, two minutes later, a tweet.

—

Fred and Kathy Santos arrived at their home in Concord, a San Francisco suburb, to find a message on the answering machine.

A reporter wanted to know what they thought of the governor’s “action.”

They looked at each other. What did the governor have to do with them?

Kathy pulled up the Sacramento Bee online. The image of Esteban Nuñez stared from the screen. Schwarzenegger had commuted his prison sentence from 16 years to seven.

Nuñez had faced the possibility of life in prison; now, just six months into his sentence, he could expect to be paroled by April 2016 with good behavior.

What had taken the criminal justice system two years to decide vanished with a signature. Schwarzenegger had exercised a singular and anachronistic power, a throwback to the age of monarchs sanctioned by Article V of the California Constitution.

Fred and Kathy Santos looked at each other, stunned, and sobbed. Their phone rang all night.

—

In his brief written rationale, which read like a summary of defense arguments, the governor said that Nuñez had no prior record and had played a “limited” role in the attack, and that it was “not in dispute” that Jett was the one who had stabbed Santos.

Schwarzenegger had denied similar clemency requests many times. In 2009, he rejected the state parole board’s recommendation to free 29 inmates who had participated in homicides but had not personally delivered the killing blows.

The governor had been unsympathetic when defendants failed to take responsibility for their crimes, or had shown “callous disregard for human suffering” by fleeing the scene and leaving victims to die.

To Jill DiCarlo, that description fit Esteban Nuñez’s crime exactly. The San Diego prosecutor described the commutation as “nauseating.”

DiCarlo had not been told in advance, nor had the Santos family. Had the governor sought her input, she would have said that Nuñez had bragged about the stabbing, that it had never been proved who thrust the knife into Santos and that Nuñez, in swiftly destroying evidence, had forever obscured the truth.

Exactly for this reason, she would have explained, the law punished both defendants equally. “They did it as a team,” DiCarlo said.

If the famously media-savvy governor had any public relations strategy beyond dropping the news at a time designed to minimize its notice, and then refusing to discuss it, none was in evidence.

Editorials and newspaper letter writers denounced the commutation as an act of political cronyism. Democrats denounced it. Republicans denounced it. Schwarzenegger’s successor, Jerry Brown, signed a law requiring that from then on, governors would have to notify prosecutors — and thereby victims’ families — before granting clemency.

Soon after the news broke, the Santos family received a letter with Schwarzenegger’s signature. “I understand why you may never comprehend or agree with my decision,” it read. “And I am profoundly sorry that my decision has added to your burden.”

Rick Clabby, who had been the case’s second-chair prosecutor, was still vexed by the plea deal that had allowed Nuñez to avoid trial for murder. He saw the sentence reduction as yet another blow to a family in pain. “The Santos family was victimized when their son was murdered,” he said. “They were victimized when our office made this stupid-ass decision. And they were victims when the governor decided to buddy up with Nuñez.”

Bonnie Dumanis, the San Diego district attorney, wouldn’t talk about why she pushed the plea deal. But when the news of the commutation broke, she joined the outrage, saying Schwarzenegger’s act had “greatly diminished justice.”

She joined the Santos family in a lawsuit to enforce the original sentence, on the grounds that the governor had flouted the state Constitution by failing to give advance notice. A Sacramento judge dismissed the suit, saying the commutation was “repugnant” but legal.

—

The bare mechanics are easy enough to determine. Esteban Nuñez obtained a form from the governor’s website. A lawyer helped him fill it out. The application for clemency went to the governor’s legal team. Then Schwarzenegger signed.

This does not describe the decisive element: what happened between a father with a deeply personal need and a man with the power to fulfill it.

In a recent interview with The Times, Fabian Nuñez put it bluntly.

“I used my relationship with the governor to help my own son,” he said. “I’d do it again. There it is. I would do it again.”

He said Schwarzenegger had followed Esteban’s criminal case closely, and the two of them had discussed it regularly. “I would brief the governor from time to time. He was a friend. He would ask, ‘How are you doing?’ He had compassion. There was no deal making, just two human beings, two fathers.”

Nuñez wouldn’t reveal precisely what he said to Schwarzenegger. But if his remarks to The Times are any indication, he spoke angrily of justice thwarted, of how his son was wronged by a deceptive, “ultraconservative” judge.

“He lied to get my son to accept a sentence which did not fit the crime,” he said. “When you’re dealing with a judge like him, and an overzealous district attorney, with a deputy district attorney who is very ambitious and is looking at their high conviction rates, the last thing that’s going to stand in their way is some Latino politician representing East Los Angeles.”

Nuñez said his ties to Schwarzenegger merely leveled a playing field that had been tilted against his son. “He corrected a wrong that a judge imposed on my son. I believe any father would do what I did.”

—

As Schwarzenegger settled into his post-politics life, the questions dogged him for a few months.

In April 2011, KCAL-TV Channel 9 reporter Dave Bryan caught Schwarzenegger slipping out the back door of a Hollywood conference where he had been celebrated for his record on climate change.

Schwarzenegger knew what was coming. He kept walking, and muttered: “Don’t ask me the same question, OK? Because otherwise you’re boring the hell out of me.”

“I think a lot of people want to know,” Bryan said. “Why did you reduce the sentence for Esteban Nuñez?”

Schwarzenegger made a loud snoring sound. He kept walking amid his entourage, his expression frozen somewhere between a smile and a grimace, as if willing the reporter out of existence. Bryan persisted.

“Governor, why won’t you talk about it? Governor? Why did you wait until the last minute, sir, before you left office? Was it a favor for Fabian Nuñez, Governor? Governor, why did you commute the sentence, Governor?”

Schwarzenegger gave his fullest public explanation to a Newsweek reporter that month.

“I happen to know the kid really well. I don’t apologize about it,” he said. “There’s criticism out there. I think it’s just because of our working relationship and all that. It maybe was kind of saying, ‘That’s why he did it.’ Well, hello! I mean, of course you help a friend.”

In his 2012 autobiography “Total Recall,” which is more than 600 pages long, Schwarzenegger makes no mention of the commutation. Nor are answers obtainable in the official file; he ordered it sealed for 25 years.

—

As a boy, Fabian Nuñez said, he watched an angry customer in La Jolla berate his father, an immigrant gardener, who told him afterward that he endured such humiliations so that his kids didn’t have to.

It is one of Nuñez’s favorite stories, one he uses to explain his need to fight his way out of the San Diego barrio, where so many others died young or went to prison.

Nuñez succeeded spectacularly. He is now a partner at Mercury Public Affairs, a leading lobbying and public relations firm whose clients include the National Basketball Assn., Verizon Communications and Uber. He reported taxable income of $2.4 million in 2013, according to court records.

How did his son, who had so many advantages, end up behind bars?

“I have no idea how that happens,” he said. “It’s very frustrating, because one generation is supposed to do better than the last. My parents came here with nothing.”

After months of reluctance, Esteban Nuñez agreed to be interviewed. He sounded wary and guarded during two brief phone calls from prison that his father arranged and listened in on.

The younger Nuñez denied killing Santos but acknowledged stabbing Santos’ two friends, saying he did it to defend his own friend.

“I hurt my victims, but I didn’t harm them in lethal ways,” he said.

“All I can do is take responsibility for what I did. I’m not going to point the finger at anybody, and I didn’t have anything to do with Luis.”

Why did he throw his knife in the Sacramento River?

“I panicked. Obviously, I wasn’t thinking.”

Why carry a knife in the first place?

“Hell of a question,” his father interjected.

The son said, “It was a time in my life I was really lost. I had a lot to deal with. I was a little insecure with myself and my ability to defend myself.”

Pressed for specifics, he said he was molested by a family member as a child — an incident he never mentioned in court, or in his letter to Judge O’Neill. He took to “numbing out” with alcohol, running from his problems.

He said he resented his workaholic father; as a boy, he rarely saw him.

“I felt like he chose work over his family,” he said.

They see each other frequently now.

“We’re closer than we’ve ever been,” he said.

A recorded voice came on the line. Time was up.

—

Fred Santos struggles, nearly four years later, to make sense of what happened. He doesn’t understand what Schwarzenegger had to gain, or what he might have owed Nuñez.

“They are definitely two Tai-Pans,” he said, using a Cantonese term for “Big Men.” The reference is from his childhood in Macau, a former Portuguese colony off the coast of China, where the powerful did not need to explain themselves.

He entwined his two fingers, held them aloft and smiled without joy. “I did not know they were like that.”

—

Last year, Kathy Santos walked into her son’s second-floor room and started boxing up his things. She took down the sports pennants and posters. It seemed like time.

She fears that she is forgetting his laugh. She pleads with him to visit her in her dreams, which she records in a journal.

“Last night I finally had a dream with Luis in it. It’s been several months and I have been feeling desperate for him.

“I was able to feel Luis’s ghost, touch him, kiss him, and talk to him, and it was wonderful. He was in the living room playing on the floor near the fireplace. He said he wanted to go to the supermarket and see what has changed or what he has missed. He said he likes to stay home now.”

In her dreams, she tries, helplessly, to reach him through a pane of glass. Sometimes dangerous animals appear — tigers, freakish crocodiles, savage birds.

In one dream, wild turkeys attacked. She broke their necks to save her son and husband.

“They were safe,” she wrote.

For a while, she and Fred went to monthly meetings of Parents of Murdered Children. She found it too hard to tell the story over and over. Therapy didn’t help.

She gets together with close friends, every week, to drink wine, light candles and share stories. They pluck from a box of inspirational cards. They have messages about love, hope and courage.

“There are some I always put back,” she said. “The ones that say, ‘Forgive.’”

—

The hills measure the seasons as Fabian Nuñez steers his BMW from Sacramento to Mule Creek State Prison, watching the countryside change color. Green, brown, green, brown, green, brown. Nearly five years down; less than two left.

He stops for coffee, to make change for the vending machines, and pulls up to the prison to ready himself for the ritual. Hand stamp. Metal detector. Door. Chain-link cage. Door. Walkway. Door.

Once in a while, people at the prison talk to him about their cases. Some strike him as victims of injustice, and ask for his help. They know him as a man with pull. He does not discourage the impression. “From time to time, I’ve been known to make a call,” he said.

“I see how deeply ineffective our justice system is. I see how easily it can be manipulated.”