Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordBBC Scotland journalist Nichola Rutherford recounts her experience of breast cancer treatment

I have breast cancer. Saying it, writing it, doesn’t get any easier. I still can’t quite believe it’s happened to me.

Last week I finished six months of chemotherapy – days before Catherine, Princess of Wales announced she had also completed similar treatment for cancer.

During 11 rounds of chemo, I’ve lost my hair, endured regular nosebleeds, and almost overcome a fear of needles.

But normal life has continued – I’ve been able to work on reduced hours, we took a family holiday and I even got to see Taylor Swift on her Eras tour.

We don’t know what kind of cancer Catherine had, or the details of her medical care. Every cancer patient receives treatment individually tailored to their disease.

All I can do is tell you how chemotherapy affected me.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordEight months ago I was a normal married mum-of-two, juggling a rewarding full-time job as a journalist with the usual parent taxi duties.

I ate home-cooked meals, enjoyed a couple of glasses of red wine at the weekend and tried to get out for a run two or three times a week.

Healthy, fit, happy. Playing by the rules.

Then at the beginning of March, just before my 45th birthday, I found a lump in my right breast.

Within days – and after a mammogram, an ultrasound and a biopsy – medics warned me there was a “strong suspicion” of cancer.

A succession of very concerned-looking nurses and doctors told me to try not to worry ahead of the formal diagnosis. Aye right, OK.

That night – alone in a hotel room in Glasgow – I was a wreck. My mind was racing, thinking about loved ones I had lost to cancer, mentally composing letters to my kids, my husband; planning my funeral.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordThe next few weeks are a blur of scans, tests, worry. There were some really bleak moments of despair.

You know that racing panic you feel in your chest when you wake up after an awful dream? I felt like that all the time – without the relief that comes when you realise it was a nightmare.

I didn’t know if I would live or die.

So when my oncologist used the words “curative intent” in a meeting to discuss treatment, I felt a huge weight lift off my chest.

It meant there was a good chance he could cure me, using chemotherapy to reduce the size of the cancer in my breast and lymph nodes, before surgery to remove it, and radiotherapy to stop it from returning.

It was at this point – before my treatment started – that the Princess of Wales announced her own cancer diagnosis. It was too raw. I had to avoid the news for a few days.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordI received the chemotherapy through a cannula in the back of my hand alongside about half-a-dozen other patients in a ward at the local hospital in Dumfries.

Sitting in large purple chairs, we are hooked up to a drip and supplied with an apparently never-ending supply of drinks, biscuits and even offered a foot massage.

The process didn’t hurt but it wasn’t pleasant. The cold cap – used to try and save your hair – left me cold to the bone; some of the medication made me sleepy.

By the end of my treatment, a visit to the chemo clinic was almost like popping in to see friends – caring, no-nonsense friends who like to stick needles in your veins.

They remember your kids’ names, your job, your sense of humour, how you take your tea – the stuff that really matters when you’re at your lowest ebb.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordI had been assured by medics before chemo that the treatment “shouldn’t be horrendous” and I remember initially comparing the side-effects of my first round to a particularly bad hangover I once had in Benidorm.

But when that goes on for days, and you haven’t the memories of a night out with friends to offset it, it quickly become wearisome.

I suffered nausea, sickness, headache and then – because of all the steroids I had to take – I couldn’t sleep at night despite being bone-tired.

My breast cancer nurses had urged me to contact them or a national cancer helpline if I had any problems. But my mind was playing tricks on me. The side-effects were grim but were they horrendous? Was the headache worth bothering them about? I was only sick once, do they really need to know? Shouldn’t I just put up with it and let the drugs do their job?

And then in the days that followed, as the sickness eased but the tiredness refused to shift, I fell into a doom spiral. I worried about my own mortality, my family, the kids; I worried about the next round of chemo.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordA change to my anti-sickness medication seemed to help with the nausea and the headaches by round two. I turned to the local Macmillan Cancer Information and Support Centre for help with the low mood.

But there was little I could do about the fatigue.

I tried to get out for a walk every day – fresh air always makes me feel better – but routes that I could run round in 30 minutes just a few weeks ago left me exhausted.

Afternoon naps became the norm. I spent a lot of time lying on the sofa and watched more episodes of Married at First Sight Australia than I care to admit to.

But every day I’d do a little bit more – maybe a pile of ironing; a supermarket shop; a coffee with a friend – and by day seven of the 14-day cycle, I was well enough to go back to work. It was the distraction I needed.

Then my hair started falling out. It’s always been quite short but it was still distressing to find clumps lying in the shower, on my pillow, inside my hat.

I had it shaved off but it started growing back when I moved on to a new, more manageable, lower dose chemo drug at the end of July.

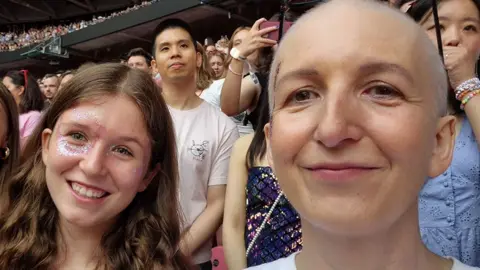

I’ve decided to embrace the GI Jane look and, to be honest, I often forget about it – at least until I glimpse myself in the mirror or feel the cold air on my scalp.

On top of that, my sense of taste changed; I have a nose bleed every morning (I hope that will clear up soon); my finger nails are brittle; my eyes water in the slightest breeze; my skin looks like it’s aged about 20 years.

But I know I’m lucky – these are mild irritations. They didn’t stop me sitting sharing my daughter’s glee at finally seeing Taylor Swift in the flesh at Wembley; or my son’s joy at tumbling down huge sand dunes on our family holiday.

The chemo has worked, the cancer has shrunk. Like the Princess of Wales, however, I’ve still got a long way to go. I have more treatment ahead of me.

Nichola Rutherford

Nichola RutherfordCatherine released an emotional video of her family to announce the end of her chemo. This time round, I found I didn’t have to avoid the news. I watched the film, read the analysis, empathised with her words.

It really does make you grateful for the simple things in life.

But it has also helped me appreciate the family and friends who have gone out of their way to help – driving me to and from hospital, popping round for a cuppa, filling my fridge with food, texting to check how I am.

Now I want to make plans – to get back to work full-time, to book some holidays, to really make the most of this second chance.

If you or someone you know has been affected by cancer, you can find help at BBC Action Line.