Following 11 years of defence cooperation and millions of dollars spent on maintaining military bases, the United States officially pulled its troops out of Niger this week in a surprise divorce that experts are calling a “blow” to Washington’s ambitions for influence in the troubled Sahel region of West Africa.

Once-close relations between the two countries saw the US establish large, expensive military bases from which it launched surveillance drones in Niger to monitor myriad armed groups linked to al-Qaeda and ISIL (ISIS).

However, those ties collapsed in March when Niger’s military government, which seized power in July 2023, cancelled a decade-long security agreement and told the US, which was pushing for a transition to civilian rule, to remove its 1,100 military personnel stationed there by September 15.

For months, the US has failed to either fully align with or outright oppose the ruling military, analysts say.

On the one hand, Washington seemed ready to maintain defence relations with the new ruling power, but on the other, it felt compelled to denounce the coup and pause aid to Niger.

A perceived slight by US officials visiting the country in December, who appeared to be pushing for a transition plan the military government had no interest in, seemed the final straw, causing the Nigerien government to issue the US withdrawal order.

“I think the US thought they could work with the junta, that they could somehow figure out a plan to kind of keep the partnership going, but a few months out from the coup, it became clear that the US and Niger had very different visions,” said Liam Karr, Africa team lead for the US-based Critical Threats Project, a conflict monitoring group.

“[The withdrawal] is going to degrade the US’s ability to keep tabs on what’s going on in the actual epicentre,” he added, referring to the conflict hotspot in the tri-border area linking Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso where armed groups hold sway.

With its strongest regional ally gone, the United States Africa Command unit (AFRICOM) is now turning to possible new partners, although its options are limited by its rivalry with Russia which is also seeking influence in the region.

Senior US military officials, including AFRICOM Commander General Michael Langley, toured parts of coastal West Africa in April including Benin and Cote d’Ivoire for what the US described as “constructive dialogue” with the countries’ leaders.

However, with its withdrawal from Niger hanging like a dark cloud, experts say Washington must now perform a balancing act: continuing surveillance missions in a revamped, less resource-heavy manner while gunning for the effectiveness achieved in Niger.

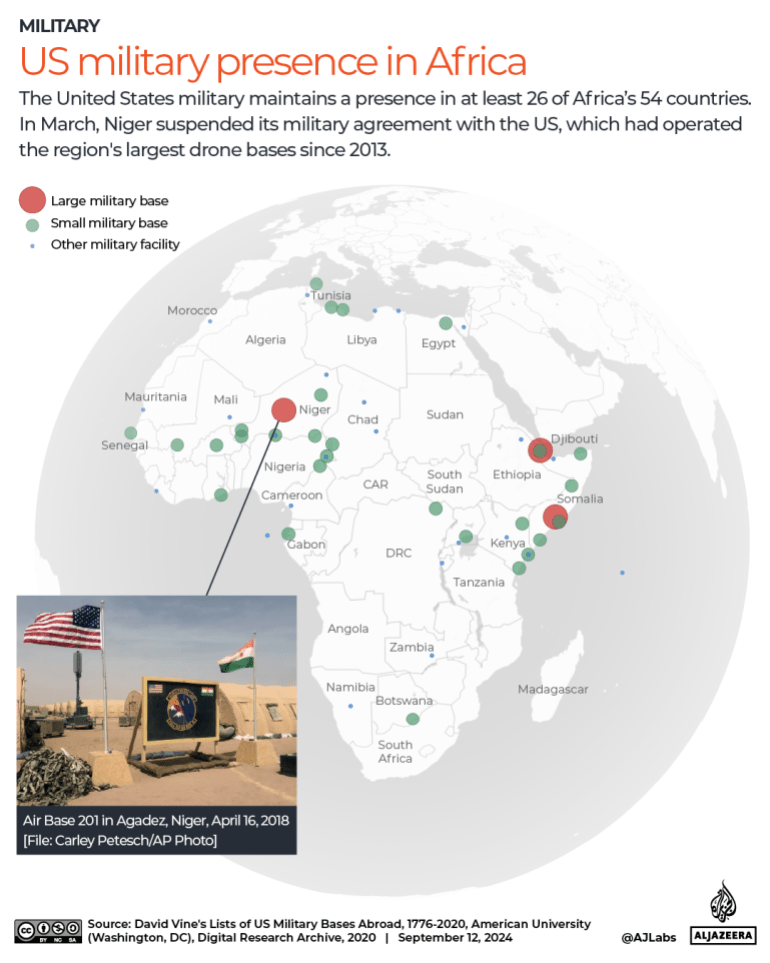

Americans in Africa

Maintaining military bases in African countries is seen by the US as an important way to monitor armed groups and respond to growing threats of armed violence before it reaches the US’s doorstep, officials often say.

Since 2008, AFRICOM has maintained a presence in 26 African countries. But some 100 US soldiers stationed in Chad were also forced to leave in May after Chad’s air force said they failed to to provide documents justifying their presence at an air base near the capital, N’Djamena.

To the east, the 5,000-man US military base, Camp Lemmonier, is positioned strategically in Djibouti from where personnel monitor the Red Sea as well as Yemen’s Houthi rebels and Somalia’s al-Shabab group. US troops also train the Kenyan army to target al-Shabab from several bases, including Camp Simba in Kenya’s coastal Lamu region.

To the east, the 5,000-man US military base, Camp Lemmonier, is positioned strategically in Djibouti from where personnel monitor the Red Sea as well as Yemen’s Houthi rebels and Somalia’s al-Shabab group. US troops also train the Kenyan army to target al-Shabab from several bases, including Camp Simba in Kenya’s coastal Lamu region.

Al Qaeda-linked Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), the Islamic State Greater Sahara branch and the Islamic State West Africa Province are seen as the greatest threats to local militaries and foreign partners like the US in the land-locked Sahel region of western Africa. Preventing those groups from expanding into coastal neighbouring countries is a key US foreign policy.

The US’s Niger exit makes clear just how much Washington’s military influence has shrunk – at least in West Africa – in recent years, experts say.

Much of this shrinkage has come about as a result of souring relations between the leaders of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger and former colonial power France.

Popular anti-French sentiment has bubbled under the surface for at least the past five years in all three conflict-racked countries, with many questioning why thousands of French and other foreign troops deployed to the region to help deter armed groups since 2013 have failed to stop armed attacks and mass displacements.

When militaries came to power in a string of coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Gabon, Chad and Niger, starting from 2020, they played on those sentiments to generate support. By December 2023, more than 15,000 French, European Union and United Nations troops had departed from Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. The three have since joined forces under the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) established in September 2023.

Russia has moved swiftly to fill the gap, deploying hundreds of Wagner Group fighters (now called the Africa Corps) to boost local militaries.

For the US, Niger’s July 2023 fall to the military was the most significant moment. Under former President Mahamadou Issoufou (2011-2021), the country appeared to have left the history of coups behind it, becoming relatively democratic and stable.

The US invested massively, building Base 101 in Niamey. The larger Base 201 in Agadez – 914 km (568 miles) from Niamey – is closer to the tri-border violence hotspot and cost $110m to build. It is one of the most expensive American bases anywhere. Together, the two bases hosted at least 900 soldiers and additional personnel to make 1,100 people.

“They did good work there,” said Ulf Laessing, Sahel researcher at the German think tank, Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung (KAS). US drones not only served as eyes, passing on intelligence about the locations of armed groups to Niger’s military, but the Americans also trained the Nigerien army.

However, Laessing said, transparency over US operations there became an issue. Several aspects of US operations were mostly unknown to local authorities and even to US lawmakers. When four American soldiers died in an ambush by the Islamic State Greater Sahara armed group (ISGS) in the Nigerien village of Tongo Tongo during an offensive mission in October 2017, Congress was shocked.

“Villagers [in Agadez] were very suspicious because they didn’t know what was happening. There wasn’t much transparency around what was going on there,” Laessing added, referring to Base 201.

Observers and commentators disagree about how effective US operations there have been overall.

While it remains unclear if US drone surveillance directly led to particular armed group leaders being neutralised, Karr said the absence of US drones does seem to have had a negative effect since.

“Attacks in Niger have become more deadly and involve larger groups of militants,” he said, referring to the period since the July coup when communications between US troops and the Nigerien army appear to have started breaking down. Before that time, incursions by armed groups in the country, unlike in its neighbours, were mostly limited to a few areas, in part because of US surveillance, he said.

However, some question whether the US military presence had an effect at all.

“If American airpower was meant to support the tracking of top targets, and if removing those targets did not fundamentally disrupt the insurgencies, then what good was all that surveillance capacity?” wrote Sahel expert Alex Thurston in the US-based journal Responsible Statecraft, in January this year.

Do or die

For the US military, it is important that American troops remain in the region, Karr said. While the US only had bases in Niger, it maintains a presence in Ghana, Senegal and Gabon.

“I think if the US left, it would essentially be sending a message that it’s a bad partner. Also, if countries are faced with challenges, they’ll partner with anyone, including Russia, which the US obviously doesn’t want,” Karr added.

With the Russia-allied Alliance of Sahel States (AES) not being an option for a base, neighbouring Ghana, Benin and Cote d’Ivoire have now become the focus of US diplomatic efforts. They’re all relatively stable, civilian-led and the US already conducts joint military exercises with the armies in those countries.

The AFRICOM commander Langley, who was part of the group which travelled to Benin and Côte d’Ivoire in April and May, told a digital news briefing on Thursday this week, that talks with the governments had taken place, adding the US was “pivoting to … like-minded countries with shared values and shared objectives”.

Laessing said the coastal countries’ increasing vulnerability to armed groups makes it likely they will accept Washington’s overtures. Benin, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are seeing increasing violence along their northern border regions by the groups. In May, the Beninese army said its troops had neutralised eight armed fighters from an unidentified group in the northeast village of Karimama, close to Niger.

US aircraft and personnel are already being redirected to Benin, according to a Wall Street Journal report this week. A US airbase there is also now being refurbished to receive them, the Journal reported.

In July, the French newspaper, Le Monde, reported that the Ivorian government had approved a US base site in the town of Odienne in the country’s northwest region. However, details about the plans for the base are scant.

Ghana already hosts the US Army’s West Africa Logistics Network – as good as a base, some say – at the Accra Kotoka International Airport.

Protesters decry increased US presence

In 2018, thousands took to the streets in the capital, Accra, after parliament signed a $20m deal that would see the US army gain access to Ghana’s radio waves and a military airbase, and allow it to import military equipment tax-free. Protesters said US troops “cause problems” – violence that might destabilise Ghana – wherever they go, referencing the general image many West Africans have of US foreign military operations.

This might be why US officials want to revamp the approach in Africa. General Langley, in the briefing on Thursday said operations going forward would be “African led, US-enabled”.

“… I listen, learn, and then we come up with a collaborative solution to be able to execute and go forward,” he added.

The Americans will try to keep a lower profile than they did in Niger, Laessing said, but they will likely face challenges anyway.

Still-present anti-West sentiment could drive more general anger against any US presence, and it doesn’t help that AES countries are not on friendly terms with many of their neighbours as well. That’s because countries like Côte d’Ivoire are seen as the “puppets” of France in parts of the region.

In July 2022, Mali detained 46 Ivorian soldiers who had travelled there to work for a private Ivorian company. Some were released in September.

“Things will get more complicated because it will take longer to fly their drones from (coastal countries) to the violence hotspot,” Laessing said. “And they’ll probably still need to overfly Niger which might be a problem with the government there and with the Russians.”