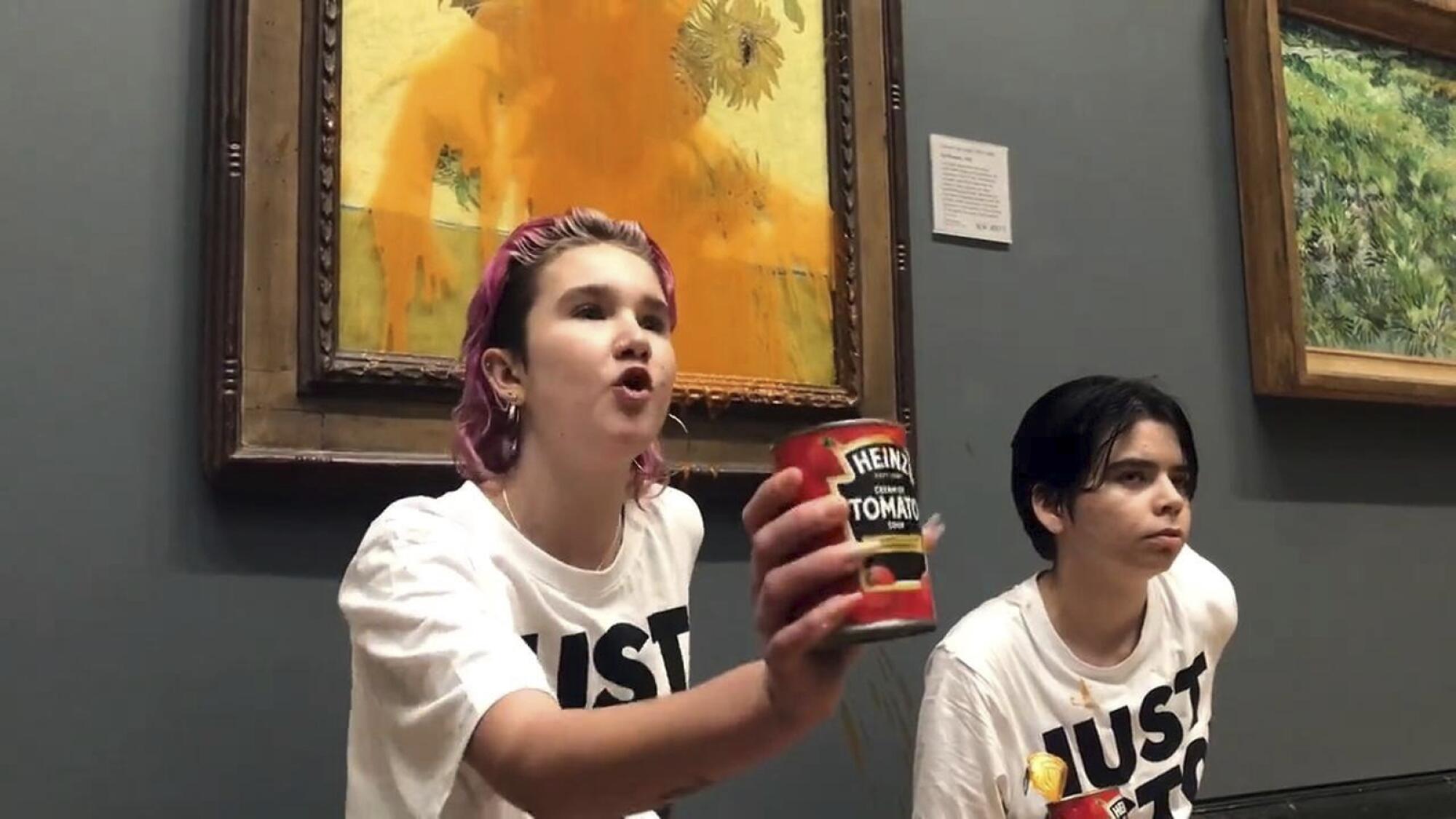

Eighteen months later, Anna Holland still can’t stomach the smell of tomato soup.

“I can’t have a tin of it anymore,” said the climate activist, who shocked the art world — and much of the rest of the planet — by throwing Heinz Tomato Soup at Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” in the National Gallery in London in October 2022.

Holland and fellow protester Phoebe Plummer carefully chose the Heinz for its bright orange hue — the same used in Just Stop Oil’s international branding — to symbolize “hope for a brighter future” in the Post-Impressionist painting.

“We used soup in particular because it would capture the media’s attention,” said Holland, a member of Just Stop Oil. “It holds the conversation for longer. It gets people to ask questions like, ‘Why soup?’”

The two protesters who threw soup at Vincent Van Gogh’s 1888 work “Sunflowers” at the National Gallery in London in October 2022.

(Just Stop Oil / Associated Press)

The splashy stunt has held the world’s attention like no climate action before, cementing the movement’s commitment to artistic vandalism. It’s a form of protest first popularized by early 20th century suffragettes — in 1914, Mary Richardson used a meat cleaver to slash Velázquez’s “Rokeby Venus” in London’s National Gallery — only to fall out of fashion shortly thereafter.

Now it’s back.

In 2022 alone, protesters threw black goo on a Klimt, mashed potatoes on a Monet, and cake at the Mona Lisa. They glued themselves to an art-history survey course’s worth of priceless works, from Picasso to Raphael to Botticelli. Not even Warhol’s famous soup cans were spared. Further assaults followed in 2023 and 2024, including a hammer attack on the aforementioned Velázquez and Just Stop Oil’s orange dye strike on Stonehenge, the mysterious 5,000-year-old monument in England.

A movement long defined by shaggy hippies encamped in old-growth redwoods and Indigenous protesters chained to construction equipment was remade in the image of two nonbinary university students wielding cans of tomato soup.

Equally unexpected, climate activists have managed to maintain their museum monopoly even as combative public protests have spilled into the mainstream.

“We knew it was going to be significant, but we had no idea it was going to be as big as it was,” said Holland. “We sort of claimed that tactic in a way, so [the public] associate it with the climate movement.”

All of which raises the question: What’s the message in the medium?

Just Stop Oil protesters sprayed an orange substance on Stonehenge in Salisbury, England, on June 19.

(Just Stop Oil / Associated Press)

“People asked me many times, ‘Why did the activists target a painting? Why didn’t they target the fossil fuel infrastructure?’” said Margaret Klein Salamon, executive director of the Climate Emergency Fund and author of “Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself With Climate Truth.”

“It’s a very frustrating complaint, because Just Stop Oil [protesters] had been arrested hundreds of times blocking fossil fuel sites, and it was barely reported,” she said. “So that’s why they threw soup.” (The Climate Emergency Fund is Just Stop Oil’s primary financial backer.)

In Klein Salamon’s view, and that of many others, the target is irrelevant. Attention is the purpose. Outrage is the goal. If pressed, some argue the indignation over the defacement itself betrays how little our culture values the planet when compared to inanimate works of canvas and pigment.

“You’re taking the risk of potentially going to prison because the government values a painting and a frame over your life and the lives of all of us,” Holland explained. “It shows the government cares more about material things than human lives.”

But that doesn’t mean there’s no role for art to play in the climate crisis — at least, not according to the art world. Grantmakers such as the Frankenthaler Climate Initiative now explicitly fund climate-focused works, while several prominent art museums have made public commitments to showcase them.

“The climate crisis is something that truly terrifies me, and also fascinates me as a subject,” said artist Josh Kline, whose new show, “Josh Kline: Climate Change,” opened in June at the Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles. “There’s very little contemporary art that deals with the climate crisis. That’s one of the reasons why I started making this work.”

Josh Kline’s “Personal Responsibility” is made up of tents and other shelters, with projections of actors playing future climate refugees.

(Joerg Lohse)

The work in question is a “suite of science-fiction installations”, spanning roughly five years’ worth of material. It was supported in part by MoCA’s Environmental Council, a first-of-its-kind initiative to transform museum operations and support artists addressing the climate crisis in their work.

“We started to place a higher premium on artists working on issues of climate change,” said curator Rebecca Lowery. “Most viewers will readily recognize the theme of the exhibition and come away thinking about what we can collectively do to avoid this future.”

At the heart of the showcase is an immersive sculpture series called “Personal Responsibility,” made up of tents and other makeshift shelters, whose “inhabitants” — projections of actors playing future climate refugees — narrate their experience of the coming disaster.

“People don’t need me to tell them that the climate crisis is happening — that’s really what scientists are for,” Kline said. “What I as an artist can do … is help make it personal for them.”

On this, Holland agrees.

“Protest is driven by art,” they said. “One of the reasons the climate movement isn’t as big as it could be is because it’s easy to intellectually connect with the climate crisis — what’s not easy is emotionally connecting.”

“That’s what art does,” Holland continued. “It’s the first step to being able to take action.”

For some, the natural conclusion of this argument is that museums and other cultural centers should be spared, invited into the conversation rather than made the soapbox for it.

“I think protest is a vital form of civic participation, and I want to honor that,” said Devon Bella of Art + Climate Action, a Bay Area-based collective working toward sustainability in the arts. “But in terms of climate activism, there’s also a lot of work that needs to be done in local communities,” work that is often less glamorous and more sustained than a brief, symbolic attack on a beloved painting or sculpture.

Unsurprisingly, the Assn. of Art Museum Directors, an industry group, takes an even more stringent view.

“Attacks on works of art cannot be justified, whether the motivations are political, religious, or cultural,” it announced in response to the soup action. “Such protests are misdirected, and the ends do not justify the means.”

Equally unsurprising, activists say that’s a cop-out.

“No one likes to be shaken awake — it’s very uncomfortable, and people get very angry at the activists,” Klein Salamon said. “But normalcy, which includes things like sports and plays and art, is actually incredibly dangerous at this time.”

Austrian activists of “last generation Austria” have splashed a Gustav Klimt painting with oil in the Leopold museum in Vienna, Austria, Tuesday, Nov.15, 2022

(Letzte Generation Oesterreich / Associated Press)

In this worldview, art about the climate crisis is at best irrelevant, and, at worst, counterproductive to the direct action necessary to stop it.

“I want to distinguish joining the climate protest movement from what most people still think of as climate action,” a.k.a. recycling your Amazon packages and toting a reusable bag to Whole Foods, the activist Klein Salamon went on. “Where we need to go is truly mass protest, hundreds of thousands of people getting in the street, occupying buildings, taking up nonviolent civil disobedience.”

Josh Kline, the artist, holds a similar view.

“There’s this displacement of responsibility,” he said of the current conversation around climate change. “Instead of saying, ‘We need structural change, we need governmental change, we need change in the political system,’ [we say] ‘It’s your responsibility as an individual to spend hours sorting your plastic and recycling.’”

Others argue that the art industry itself shares complicity in the crisis, even as artists and museumgoers are largely aligned in their desire to confront it.

“Art throughout history has been intrinsically connected to wealth and finance,” said L.A.-based artist Sayre Gomez, whose paintings of Los Angeles highlight destruction and decay. “[But] artists and activism overlaps in most cases. It’s artists typically who are aligning with the spirit of protest. So there is a bit of a double-edged sword there.”

Although their methods may be different, both the activists and the artists agree they are locked in an arms race to keep public attention on the emergency unfolding before them.

And that’s where soup may finally be losing steam.

Even Klein Salamon acknowledged that, 18 months after “Sunflowers,” the effect of political vandalism may be wearing off. Nothing shocks in perpetuity — not “The Rite of Spring” or “Piss Christ” or “Pink Flamingos.” Like the art it defaces, protest must evolve to stay relevant.

“Something that works once or twice or three times doesn’t work forever,” Klein Salamon said. “It loses its shock.”