I became a one-way pen pal for democracy in 2018, writing letters and postcards to strangers in the lead-up to that year’s midterm elections.

I had spent the months before marching for women, science, immigrants and Muslims. Then I decided marching wasn’t enough. I needed to engage individual Americans about electing politicians who shared my values.

So that September, I attended a grassroots event to learn about volunteer voter outreach hosted by a Los Angeles group called Civic Sundays. We could choose to learn how to knock on doors, call and text prospective voters or write postcards to engage people.

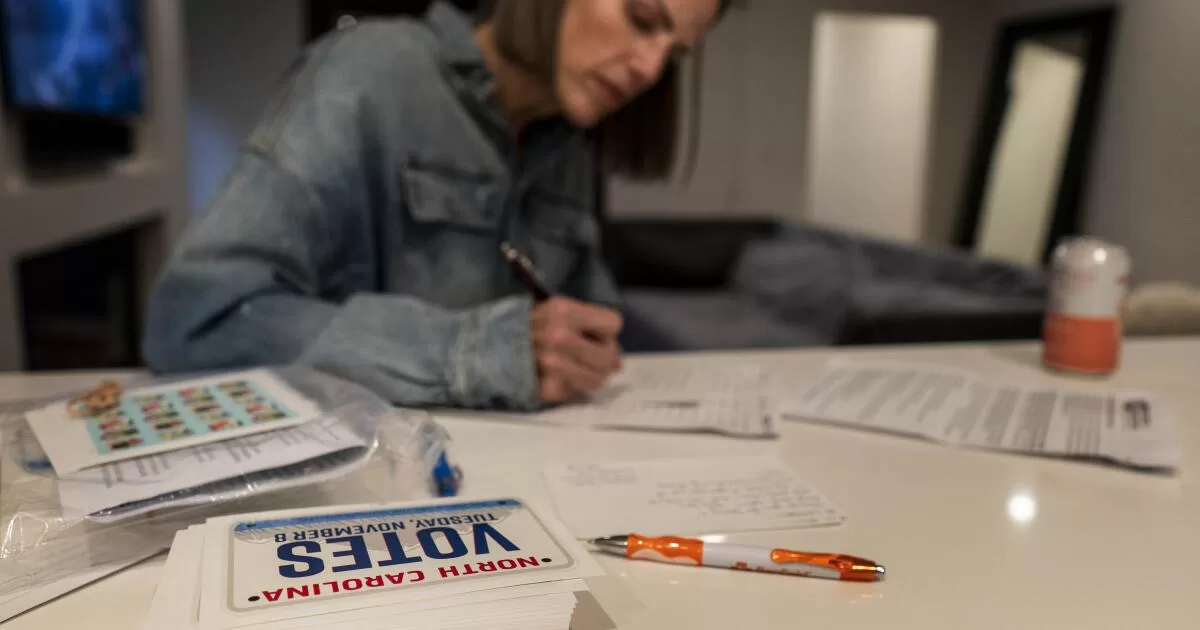

I’d never heard of writing postcards to strangers as a way to encourage them to vote. But I was charmed by the thought of an analog means of saving democracy. Civic Sundays and other organizations, many of which sprang to life following the 2016 presidential election, supply volunteers with lists of names and addresses of registered voters. The writers supply penmanship, stamps and sometimes the postcards themselves.

I joined a large table of people with seemingly professional-level glitter and Magic Marker skills. While their postcards looked like illuminated manuscripts, I painstakingly struggled to make mine legible. A fourth-grade teacher once told me my writing resembled a hostage taker’s ransom note, but fortunately, I didn’t have to take a handwriting test to get a seat at the postcard table (some organizations do actually require one).

I found the work rather wholesome, but I wasn’t sold on the idea of trying to engage a population that couldn’t be bothered to vote.

The more postcards I wrote, the more I started to wonder: Who were these infrequent voters? Why weren’t they doing their civic duty? If I looked their address up on Google Maps, what would I see? Unmown lawns? Gated mansions?

I became racked by a desire to know who exactly were these shirkers of civic responsibility. But we’d been given clear instructions: Do not personally engage the recipients of your missives. Instead, we followed a clear and concise script of just a few sentences.

I participated in another postcard-writing campaign for the 2020 presidential election. This time, I specifically requested names from a swing state, Michigan. As I wrote to these strangers, I became increasingly frustrated, imagining them enjoying their weekends without a scintilla of voting guilt while I agonized over whether they might be offended by a postage stamp with a cat on it.

When I mentioned these frustrations to a cynical friend, he told me to read the Trappist monk Thomas Merton’s famous 1966 “Letter to a Young Activist.” I should have been suspicious, seeing as my friend would be the last person to write a postcard to a stranger. Sure enough, Merton’s words did not reassure me about the fate of my postcards. “[D]o not depend on the hope of results,” he wrote. “When you are doing the sort of work you have taken on, essentially an apostolic work, you may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect.”

After reading Merton’s letter, I spent some months not writing the scofflaw voters of Michigan, Georgia, Arizona or anywhere else.

But when the 2024 election campaign started up, with the future of the country once again on the ballot, I asked for another postcard list.

This time one of the choices was to write to people in my own state, California. This felt more like writing a neighbor than someone far away and utterly unknown. Once I had my list and started reading the names and addresses, I realized some of my postcards would be going to people who lived near the town where I work.

And then it happened. I recognized a name. The Gen Zer who needed a nudge to vote was one of my thoughtful, capable students.

I finally had an answer about the people I was writing to. They were just like the rest of us: unmarried singles and matriarchs of big families, people who drive electric cars and people who drive big trucks, charming people and irritating people and neighbors who played their music too loud but were sweet with their kids. People so busy leading their lives they sometimes forgot or opted not to vote.

Recognizing just one name made me certain I had to keep penning these epistles of democracy, to keep reminding others, even if they didn’t listen or want to hear it, that their vote mattered. With new insight into Merton’s famous missive, I had to put my trust in, as he put it, “the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.”

Melissa Wall is a professor of journalism at Cal State Northridge who studies citizen participation in the news. This article was produced in partnership with Zócalo Public Square.