London, United Kingdom – As a 16-year-old schoolgirl in her classroom at Plaistow Grammar School in London’s East End, Leila Hassan Howe, now 76, can still remember being made to feel unwelcome.

She had returned from Zanzibar to live with her English mother in the United Kingdom, where she was born in 1948. Her father had moved back to the East African nation, and for a time she lived with him.

In 1964, she was one of only three Black girls at her school. They were regularly taunted in the playground.

Children would say to her: “My dad says they have come to take our jobs, and why are they coming into this country?”

“They” meant “us”, explained Hassan Howe, a veteran activist of the UK’s Black Power movement in the 1970s, a decade during which racism against immigrants from the Commonwealth was on the rise in Britain as the far right gained traction.

East London was then a white working-class neighbourhood, still emerging from post-war destruction.

“[Many Britons] felt that the little they had gained since the second world war, under the Labour government, was going to be taken away by immigrant labour,” said Hassan Howe.

More than 50 years later, a similar narrative has fanned the flames of hatred. The widespread race riots that erupted earlier this month across Britain brought back painful memories for ethnic minority pensioners. Like in the 1970s, far-right agitators went on the attack against immigrants and non-white Britons.

Although the latest unrest has been quelled as police have meted out tough sentences and antiracism protesters stood in solidarity with those affected, Tariq Mehmood, an antiracism activist and English professor now in his mid-sixties, fears further riots.

“I’ve heard people say racism is tearing this country to pieces. It’s not”, said Mehmood, the co-founder of the United Black Youth League. “It’s the cement that made it and is holding it together because its institutions remain infested with the historical ideology of colonialism.”

‘How am I going to take myself out of that colonial history?’

The August riots, Mehmood suggested, are rooted in an ideology that’s been festering for centuries.

“I became part of this country [UK] in 1846 for the simple reason they sold my ancestry. They sold my lands. They sold all of us for 300,000 pounds in the Treaty of Amritsar. So how am I going to take myself out of that colonial history?”

The scapegoated post-war immigrants had been invited. From 1947, the UK government asked people from its former colonies to relocate and help rebuild a post-war Britain, and they found work in transport and nursing.

Bradford’s textile industry became home to a large predominantly Pakistani community, often working night shifts and undesirable hours.

That’s where Mehmood’s grandfather settled, finding work at Drummond Mill in Manningham.

By 1967, aged eight, Mehmood joined his male relatives, arriving from Potwar, in Pakistan’s north Punab region.

He described his childhood as “dreadfully violent”.

“You know it’s to do with skin colour, because from every part of society you’re called a P**i, a Black b*****d, a c**n, a w*g. There’d be people rubbing our faces to see if the colour would come off.

“We didn’t need to hear Enoch Powell speak, we were feeling the boots and the punches and the kicks,” he said, referring to the British politician’s inflammatory Rivers of Blood speech in 1968 that called for repatriation and stirred racial hatred.

The far-right National Front party was formed the same year that Mehmood arrived while three other xenophobic groups merged – the League of Empire Loyalists, the British National Party and the Racial Preservation Society.

Curbing immigration became part of its manifesto and its membership grew. While its numbers rose, so too did those of the Black and Asian antiracist movements.

A year later, maximising the populist racism and anti-immigration sentiment, Conservative Party MP Powell took to the podium to warn the nation against opening the “floodgates”.

Migrants, as well as Black and Asian people born in Britain, openly challenged discrimination and pushed back especially after racially aggravated murders that the police were accused of turning a blind eye to – like that of Gurdip Singh Chaggar in 1976 in Southall, the Khan family arson attack in Walthamstow in 1981, and New Cross tragedy that same year in which 13 young Black people died in a fire.

Alleged police inaction and racial provocation at the handling of New Cross led Hassan Howe to co-organise the Black People’s Day of Action along with her husband Darcus Howe, the well-known leader of the British Black Panthers.

Twenty-thousand people marched in what would be the largest demonstration of Black people in the UK at the time.

“It was much more dangerous back in the 70s and 80s. The police attitude was different to what it is now, the police were not on your side,” the Grenada-born broadcaster, journalist, musician, composer, oral historian and educator Alex Pascall OBE told Al Jazeera.

The 87-year-old arrived in Britain aged 20. He went on to host the first Black British radio show on the BBC and co-founded The Voice newspaper.

In the 70s and 80s, he had several unprompted run-ins with the police.

“One evening dressed like a turkey cock, that means your feathers are all out, and you’re feeling good, I was arrested and beaten by two plain-clothed police officers,” he said.

In another incident, a colleague at work told him he was not “British enough”. He also remembers being called a “n****r” on the streets.

Pascall and his Black friends became so aware of the police that they learned how to quickly hold both hands tightly together when arrested.

“Because if you don’t, they’ll say you hit them or something.”

There was no police protection, he said, so they found ways to defend themselves.

‘People only express their racism when they feel they have the power to’

These days, Pascall is optimistic.

He believes a change in police attitudes quelled the August riots. Officers served to protect antiracist protesters this month and arrested the far-right rioters at pace, a stark contrast to four decades ago.

“You now even have Black people in the police force,” he added.

Mehmood has less hope.

He is doubtful that the nature of policing has systemically improved, instead suggesting “they’ve just got a lot of lipstick on”.

“Ultimately the police will protect those who give the orders. They’re an instrument. They do not have the willingness to confront white racists and it will be proven in the coming months,” he said.

In 1981, when Mehmood was in his 20s, the apparent lack of police protection saw non-white communities find their own means to defend themselves.

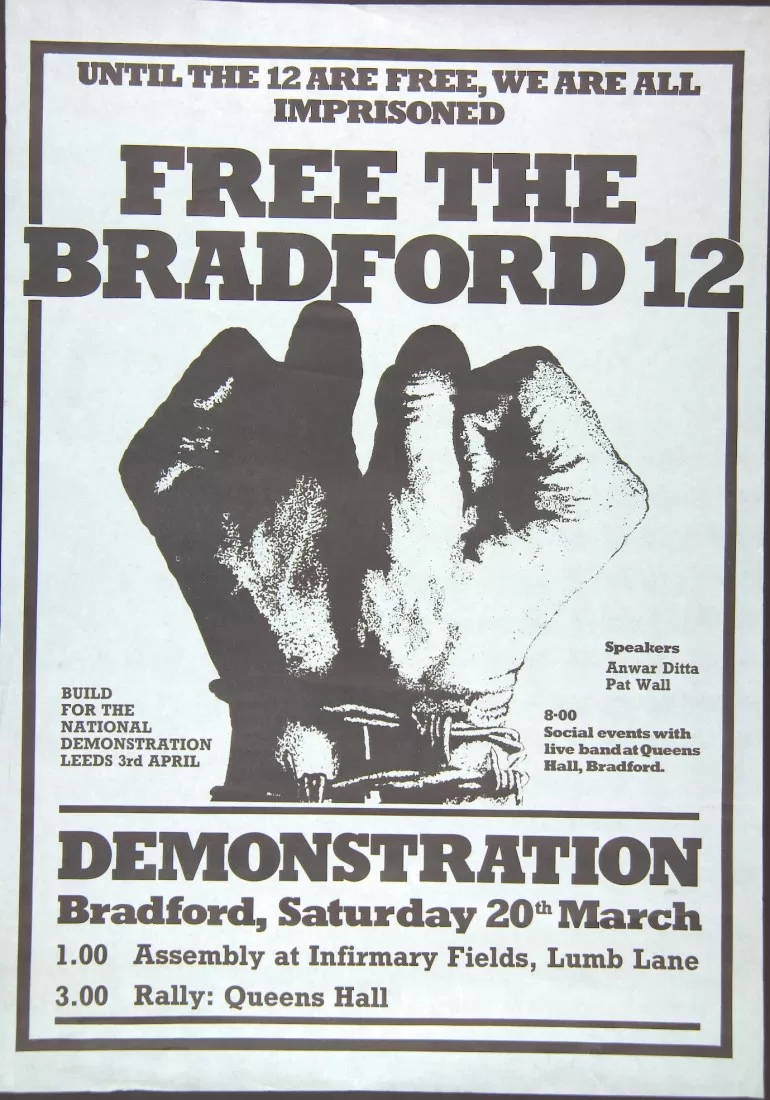

On hearing of a planned armed march by members of the National Front through Manningham, Mehmood and 11 others, who became known as the Bradford 12, made petrol bombs out of milk bottles as an act of self-defence.

“We were scared, because what else could you do? Your houses would get petrol bombed. You’d get stabbed, battered, punched,” said Mehmood.

The march was ultimately cancelled and the bombs were never used.

The Bradford 12 were charged and arrested. But in a landmark case, they argued they were acting in self-defence which led to their acquittal.

Movements like Mehmood’s and the Black Unity and Freedom Party that Hassan Howe joined in 1971 demanded racial equality in housing, healthcare and education, while simultaneously taking on the justice system and countering police brutality.

“We had defeated racism by the late 80s,” Hassan Howe said.

But now it’s the “political class” that has once again allowed people to be racist and to “pronounce their racism … that’s why it’s happening again,” she added. “People only express their racism when they feel they have the power to.”

The recent riots came in the aftermath of a fatal stabbing in Southport during which three young girls were killed. Far-right activists and online influencers such as Tommy Robinson and Andrew Tate, as well as hard-right politicians including the leader of the Reform UK party Nigel Farage, are accused of whipping up hatred by ranting in social media posts about migrants, Muslims and the police, alleging that Britain has loosened its borders to allow violent crime.

Migration was also a key campaign issue ahead of the July 4 election, which ushered in the first Labour government in 13 years. The Conservatives spent years promising to curb undocumented migration with its coined phrase “stop the boats”, a pledge that Labour has, albeit in a softer manner, adopted.

Meanwhile, conspiracy theories, though quickly debunked, suggested the Southport attacker was a Muslim and a migrant and within days, several towns and cities were grappling with a level of violence and panic not seen in years as agitators attacked people, homes, businesses and hotels that housed migrants.

“By the early 90s, even if you were a racist you wouldn’t articulate it in the way that it’s being articulated now. It was wrong to be racist,” said Hassan Howe.

To an extent, Tariq Mehmood agrees. “Fascist arguments” have become mainstream arguments, he said.

“Without racism, the colonial and slave empires couldn’t work,” and it’s this principle, he argued, that has trickled down to those behind the August riots.