Reuters

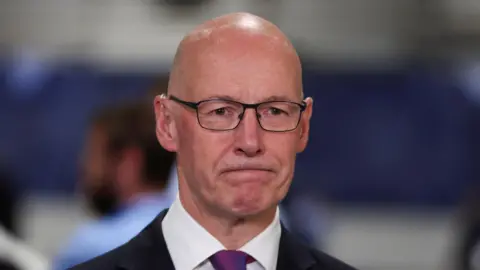

ReutersThe SNP has spent the summer licking its wounds after that bruising general election defeat on 4 July.

The day after the party lost 39 seats and half a million votes, John Swinney admitted a period of “soul-searching” would be needed.

The first minister has been speaking to party members around the country over the last couple of months, seeking feedback, analysing what went wrong and considering what’s next.

In the aftermath of the election, Mr Swinney said the SNP needed to be healed and “needs to heal its relationship with the people of Scotland”.

That prospect looks all the more difficult now, given the party of government at Holyrood is facing down some severe financial challenges, both in the immediate future – and longer term.

The leadership goes to its conference this weekend, as it prepares to announce a raft of spending cuts when MSPs return from recess next week.

Universal winter fuel payments, funding for nature restoration and cheaper rail fares have been hit already – and there is more to come.

Privately – and in some cases publicly – senior Scottish government figures are very downbeat.

The scale of the challenge to balance this year’s budget will, they say, mean painful choices.

And there’ll be no let up for 2025/26, with Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer warning “things will get worse before they get better”.

Tough financial decisions at Westminster of course have a knock-on effect for Scotland’s grant funding.

Meanwhile, the issues that divided the SNP prior to the election are well-rehearsed – they include the pursuit of gender recognition legislation and its strategy over independence.

A sense of dissatisfaction with the leadership, seen by some as closed off and unwilling to listen to the wider membership, also bred resentment for years.

More recently the implosion of the power sharing deal with the Greens and the subsequent resignation of Humza Yousaf created a sense of instability.

And since the election, the decision for the Constitution Secretary Angus Robertson to meet with Israel’s deputy ambassador to the UK caused an internal backlash.

And that is the backdrop to which John Swinney will address the SNP conference for the first time as first minister.

He has two main challenges – the first is to try to unite and motivate the membership.

The second is to lay out a new vision for government.

Neither of those are going to be easy.

Vision for the future

With no clear route to delivering a second referendum – and Mr Swinney himself admitting after the election that the party is failing to win the argument with the public – the glue that bound the so-called broad church of SNP members now threatens to come unstuck.

Meanwhile, the first minister’s vision for the future needs to convince more than just his own party.

It has to be one that can persuade voters to re-elect the SNP at the 2026 Holyrood elections.

That is a tough ask for a government that will have been in power for almost two decades by then.

And Mr Swinney isn’t exactly a fresh face, having been a senior figure in both Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon’s administrations.

Is he really the man to be bring about the transformation of the SNP that many in the party say is required?

And can he really deliver that when many of the key posts in his own Cabinet are filled by those who served under Nicola Sturgeon?

Several of those MPs who lost their seats in July now believe the same fate awaits their Holyrood colleagues.

Some of those MSPs believe it too.

Mr Swinney’s ultimate test is to prove them wrong.