The filmmaker expected his subject to be angry. To cry or scream, curse him out. He had, after all, betrayed her.

For two years, Eric Goode, the producer behind the mega-hit “Tiger King,” had purposefully concealed his identity from the star of his new documentary series. Her name was Tonia Haddix, an Ozarks-based exotic animal broker who was obsessed with chimpanzees. And Goode would ultimately play a key role in having the “humanzee” she considered her child, an ape named Tonka, removed from her home.

Yet when Goode and Haddix finally came together for a filmed face-to-face, she was cordial. Friendly, even. “She was so surprisingly OK with it,” the director, 66, recalls now. “Almost to the degree where she felt more important because it was me.”

In fact, Haddix allowed the production’s cameras to trail her for another year and a half, culminating in “Chimp Crazy,” the four-part docuseries that premiered on HBO and Max this month. Now that the program is out, however, Haddix — who did not respond to multiple inquiries from The Times — is publicly saying she never would have participated if she’d known from the outset that it was a Goode production. Critics, too, have called the series’ ethics into question, voicing concerns about what standards should apply to nonfiction filmmakers, especially those making series with high entertainment value.

“Chimp Crazy’s” main subject, Tonia Haddix.

(HBO)

Goode admits he doesn’t know how he identifies: Journalist? “I don’t think so.” Animal rights activist? “No. I’m more of an animal welfare guy.” He wasn’t even a filmmaker before “Tiger King.”

Goode does not necessarily feel obligated to follow the educational or ethical guidelines by which conservationists and journalists abide. Without these “indoctrinated boundaries,” as he calls them, he has the freedom to find — or, in the case of “Chimp Crazy,” provoke — dramatic on-screen conflicts and satisfying resolutions that traditional documentarians might not. Still, Goode’s own discomfort with the tactics he employed against Haddix points to the pitfalls of this approach. He may not characterize himself as an activist, but his work as a filmmaker originated with his desire to protect exotic animals — and any viewer of “Chimp Crazy” or “Tiger King” who isn’t aware of that background is liable to feel unmoored.

With its cast of outlandish characters and a well-timed premiere date — it launched on Netflix in March 2020, right when COVID-19 lockdowns forced everyone indoors — “Tiger King,” a seven-episode exploration of the world of private tiger ownership, became one of the wildest successes of the streaming age. It made subject Joe Exotic, an eccentric felon with an affinity for mullets, tattooed eyeliner and big cats, into a household name. It propelled Carole Baskin, Joe’s archnemesis, onto “Dancing With the Stars.” And in 2022, the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which makes it illegal for private citizens to purchase animals like lions, tigers and leopards, was finally signed into law by President Biden after a decade of advocacy by animal rights groups.

Goode is not a big-cat aficionado himself, but he’s been drawn to reptiles since he was a boy. Growing up in Sonoma in Northern California, he and his four siblings roamed the family’s land, playing with spiders and snakes. It was the gift he received on his 6th birthday that most captured his attention, though: a Greek tortoise, whose shell would go on to become the logo for the Turtle Conservancy he opened in Ojai in 2005.

In his 20s, Goode was a nightlife fixture in New York City, co-founding Area, the 1980s club that featured art installments and merchandise from the likes of Keith Haring, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. He would go on to launch such establishments as the Waverly Inn, the Bowery Hotel and the Jane Hotel. He palled around with Madonna, dated Naomi Campbell and directed a couple of Nine Inch Nails videos — one of which, “Pinion,” was so racy that MTV wouldn’t play the full thing on air.

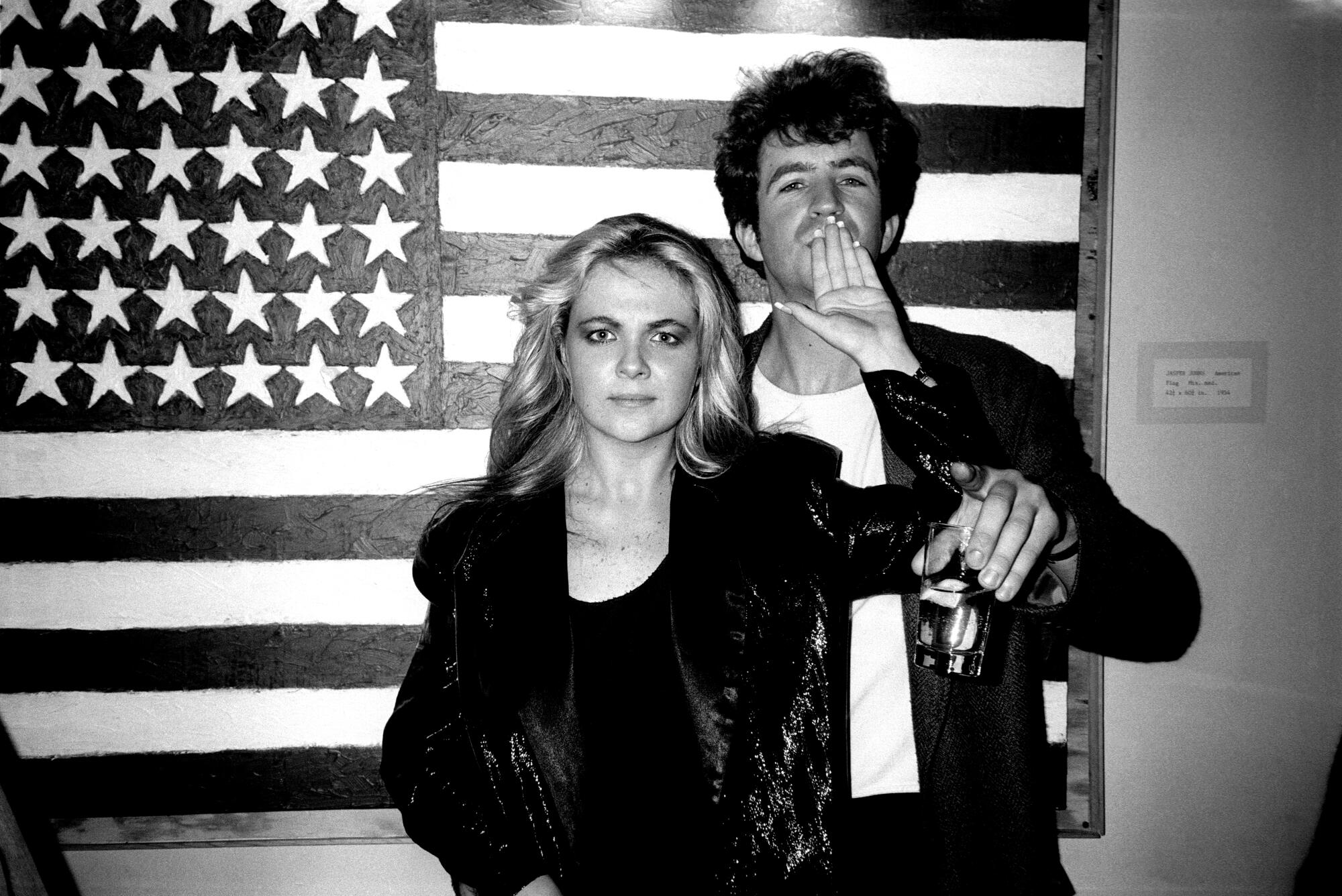

Goode at his club Area with Cornelia Guest in 1985.

(Patrick McMullan / Getty Images)

It was during this era that Maurice Rodrigues, then a part-time zookeeper at the Bronx Zoo, first encountered Goode. When the fish tank broke at Goode’s now-defunct restaurant the Park, Rodrigues was called in for a repair. Afterward, Goode invited him to dinner there.

“I’m in my early 30s, just this little Jersey boy, and we’re sitting at the best table in the place surrounded by actual models,” Rodrigues remembers. “But Eric and I started talking about turtles so much that we completely ignored these beautiful women. Finally, they got frustrated and said they were leaving. And Eric’s like, ‘OK, bye!’”

Bonded by their love of chelonians — turtles, terrapins and tortoises — the two men began traveling the world together to research the reptiles. But they found the Turtle Survival Alliance conferences they attended to be drab. Instead of listening to boring lectures regurgitating scientific papers they’d already read, why not present video footage?

“Our aim was to try to buy animals from poachers and catch them on camera,” says Rodrigues. “We got undercover cameras and found a pair of eyeglasses that had a spy camera in them. I thought we were going to maybe get killed.”

Then, in 2009, “The Cove” came out. The documentary, in which a team set out to secretly capture a bloody Japanese dolphin slaughter, was named the best of the year at the Academy Awards. “That’s when Eric said, ‘Let’s not do these little amateur films anymore,’” says Rodrigues. “‘Let’s do something for a global audience that we can pitch to anyone, and if it’s successful, maybe we can raise money for conservation.’”

Goode during the filming of “Chimp Crazy.”

(HBO)

Using his own money, Goode began bringing a small professional production crew along on his travels with the aim of making a project about the extinction crisis. CNN got wind of the footage and committed to shooting a pilot for a TV series. The network ultimately passed on the show in 2019, but after “Tiger King,” Goode started to revisit some of the topics he’d been interested in for his next project.

“We were looking at bushmeat markets in Southeast Asia, female trophy hunters, butterfly collectors,” said Jeremy McBride, Goode’s producing partner. “We wanted to explore this broader theme of individuals’ relationships with exotic animals.”

That’s when things started heating up at the Missouri Primate Foundation. The facility’s owner, Connie Casey, bred chimpanzees that starred in movies, appeared on Hallmark greeting cards and appeared at children’s birthday parties — including a chimp named Travis, whom she sold for $50,000 when he was an infant, and who went on to attack a Connecticut woman named Charla Nash in 2009, ripping out her eyes, nose, lips and nine fingers.

After receiving a dozen citations from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Casey was sued in 2017 by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which claimed she had violated the Endangered Species Act. That’s when Haddix, trying to purchase a chimp, learned about Casey’s struggles and agreed to take legal ownership of the animals in the hopes of helping her new friend evade trouble.

But PETA did not relent. In 2020, the organization negotiated an agreement with Haddix that stipulated she could keep some chimps on the Missouri property if she renovated and expanded their facilities.

It was in the midst of this legal back-and-forth, in June 2021, when Haddix received a phone call from Dwayne Cunningham.

“Don’t ever say anything to me that you don’t want the whole world to know,” Dwayne Cunningham, “proxy director” and a former Barnum & Bailey clown, says he told Haddix. “And Tonia being Tonia, she just kept talking.”

(HBO)

Goode brought in the former Barnum & Bailey circus clown, who was sentenced to 14 months in federal prison in 1999 for trafficking tortoises and endangered iguanas, to be his liaison to the reclusive Casey, who hadn’t granted an interview to anyone since the journalist Peter Laufer for his 2010 book, “Forbidden Creatures.” If she was going to talk to anyone, Goode surmised, it would more likely be a guy whose “livelihood was also shut down because of animal rights groups” than the guy who made “Tiger King.”

Cunningham was open to the assignment because, as an animal lover, he wanted to see with his own eyes if the chimps were truly being mistreated. Likewise, Goode couldn’t forget what Laufer — a friend who is also on the advisory board of his Turtle Conservancy — told him about his time in Missouri.

“Peter described it as being so horrific — that he’d done prison interviews and been in civil wars, and nothing prepared him for it,” says Goode. “What made me feel like it was worth it, morally and ethically, was the knowledge I had about what was going on inside that house. I thought: ‘You know what? The end justifies the means, in this case.’”

The plan worked — sort of. Though Casey never agreed to an interview, Cunningham did win over Haddix. She later told Rolling Stone that she agreed to be part of the project because Cunningham was “a big animal person” who “would even come out early just so he can help bottle-feed some of our baby hoofstock.”

With her collection of wigs, eyelash extensions and spray-tanned body, the 54-year-old made for a visually intriguing subject. Plus, she was forthcoming, admitting to the cameras that she cared more about Tonka than her own human son.

Haddix’s use of eyelash extensions, lip filler and other cosmetics are a key part of her depiction in the docuseries.

(HBO)

Just days after the film crew arrived in Missouri, a judge ruled that all seven of the chimps who lived there would be sent to a Florida ape sanctuary because Haddix had not renovated the habitat to the standards previously agreed upon with PETA.

But when local sheriff’s deputies and the U.S. Marshals Service arrived at the Missouri property to seize the seven chimps on July 28, 2021, they found only six animals. Haddix told them the missing primate, Tonka, had died on May 30 from heart failure.

As “Chimp Crazy” reveals, however, Haddix had sneaked her most beloved chimp to a friend’s house in Ohio. From there, she moved Tonka to her home near the Lake of the Ozarks, where she had outfitted her basement with a cage.

Almost immediately after kidnapping Tonka, Haddix let the documentary crew in on her secret. But she still did not know that Goode was behind the project — something he was increasingly “not fully comfortable with,” he acknowledges. “I don’t want to be that kind of person. I just kept thinking, ‘When is the right time to tell her that this is me?’ I always kind of thought it could have been sooner.”

The crew, meanwhile, was growing concerned. Haddix was in the dark, and now they had unwittingly become accessories to a crime. Alan Cumming, who starred with Tonka in the 1997 film “Buddy,” teamed up with PETA to offer a $20,000 reward for information about the chimp’s whereabouts. Cunningham, who is referred to as a “proxy director” in the series, says he and some camerapeople raised these issues with their bosses.

“I’m sure it was hard for the crew to have to understand that maybe there’s a greater good in not acting so quickly,” Goode says. “It was a very unsettling period. I was talking to my primatologist friends and saying, ‘If I don’t do something, is this chimp going to be OK?’”

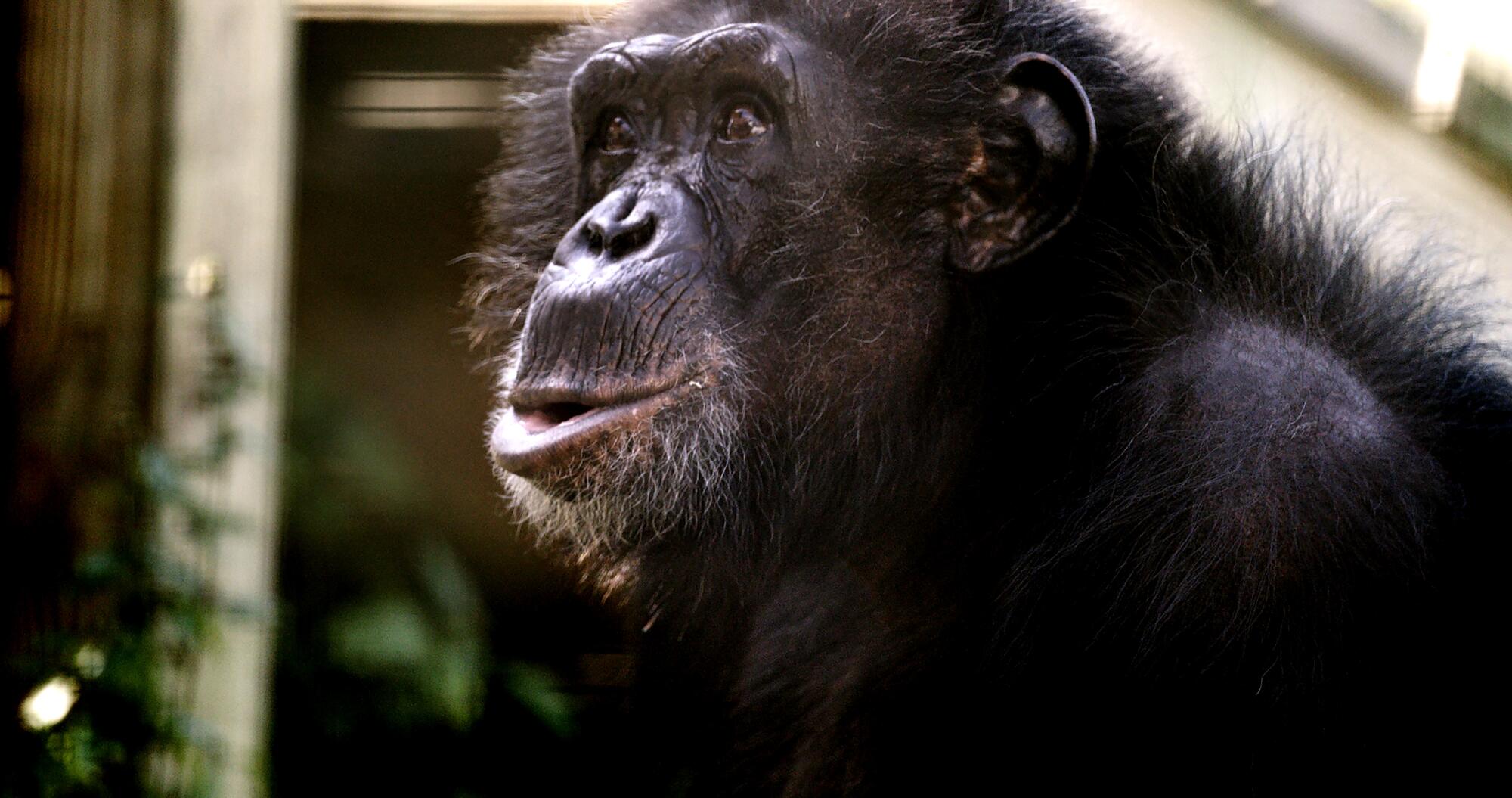

Haddix with Tonka the chimp.

(HBO)

Goode shared video of Tonka from the basement with the scientists, who attempted to identify physical tics that indicate mental distress. Cunningham shared his own observations of the chimp with Goode: Tonka was clean. He wasn’t having anxiety attacks. Yes, Tonia occasionally fed him Happy Meals or Powerade, but “he was always loved,” Cunningham says.

In May 2022, Haddix confided to Cunningham that she planned to euthanize the chimp; she said the animal’s veterinarian told her Tonka was so unwell it was cruel to keep him alive. Cunningham notified Goode, who decided it was finally time to tell PETA where Tonka was.

The producers called PETA on May 30, 2022, and requested an in-person meeting. The next day, they met with the organization’s lawyers. On June 1, PETA filed an emergency motion to remove Tonka from Haddix’s care.

“We would have wanted to know the moment the filmmakers found out that Tonka was in Tonia’s basement,” says Brittany Peet, the PETA Foundation’s general counsel for captive animal law enforcement. “I’m incredibly grateful that they did ultimately loop us in so we were able to get Tonka out. I don’t think that every documentary filmmaker would have made the choice that they did, called us and risked their project to save a life.”

In the days leading up to Tonka’s removal on June 5, 2022, Haddix was still in the dark about who had revealed her secret. She confessed as much to Cunningham, who wore a hidden camera when he went to talk to her during that period.

“I didn’t feel guilty,” Cunningham insists. “I always said to Tonia, ‘Don’t ever say anything to me that you don’t want the whole world to know.’ And Tonia being Tonia, she just kept talking. So I didn’t feel guilty; I felt like I was doing my job. But I felt bad for a friend, because I could see that the love story was spiraling out of control.”

When he learned Tonka was hidden in Haddix’s basement, Goode says he wondered, “If I don’t do something, is this chimp going to be OK?”

(HBO)

When he eventually met Haddix, Goode began by telling her that he related to her. “There are certain animals,” he says in the series, “that if people took them away from me, I would be very, very upset.”

He was referring to the chelonians he keeps on his Ojai property, where approximately 40 endangered species of turtles or tortoises live. While he says he does like being around them for “selfish reasons,” the animals reside in Southern California because they’re either extinct in the wild or so endangered that poachers pose a critical risk to the remaining population. “I don’t want to say I’m, like, trying to create a loophole for why I can keep a tortoise and someone can’t keep a chimp,” he says. “It would certainly be better to keep our animals in the wild, just because the environmental conditions are very hard to replicate.”

Goode has been a controversial figure in conservation circles. Craig Stanford, a human evolutionary biologist who has led USC’s Jane Goodall Research Center, says his colleagues often question his association with someone who directed something “really trashy” like “Tiger King.” (He is on the Turtle Conservancy’s Board of Directors and sat for a “Tiger King” interview that was eventually cut.)

“How dare you capitalize on these gorgeous, endangered animals to make millions?” Stanford says, describing his peers’ criticism. “I say, ‘Well, OK, yes, but he did shine a light, and it did lead to stricter regulations. And he did donate some of the proceeds from it to a very good cause.’” (Goode says he and two other “Tiger King” partners donated $1 million of the series’ proceeds to a program for tigers in the wild in India.)

Such judgments are enough to make Goode wish one of his other, non-animal-centric projects — such as a documentary he recently shot about his late mother — was being released before “Chimp Crazy.” “That way, people wouldn’t think I’m just using this model of ‘Tiger King’ and that’s all I can do,” he says.

Goode says he hopes “Chimp Crazy” doesn’t leave audiences thinking he’s “using this model of ‘Tiger King’ and that’s all [he] can do.”

(Emil Ravelo / For The Times)

Haddix, he says, has been having a difficult time with the film’s release. A few weeks ago, Cunningham traveled to St. Louis to screen all four episodes for her. After she watched the first one, which features the most video of her with Tonka, he says she cried in his arms. Then there was silence. “I told her she had to get up off the couch because we had to move it back,” Cunningham says. “She started laughing, and that kind of broke the ice a little bit.”

They’ve continued to exchange text messages, as have Haddix and Goode. The director says Haddix requested a number of “Chimp Crazy” posters be sent to her so she could sign and sell them. In public, however, she seems to be presenting a different story. And that upsets Goode.

“She said that I offered her money so she would continue to film with me, or guaranteed she could go see Tonka — both of which are absolutely, categorically not true,” he says, noting that the production did pay her for use of some archival footage.

The way Goode sees it, Haddix would have been caught eventually, with or without him. By her own admission, she told friends, family and neighbors that Tonka was in her basement.

“So yes, we are the bad guys — we turned her in. But I think that was inevitable,” he says. “I just try to use the moral compass that my mother gave me in life. I don’t know where that falls, but there definitely is one.”