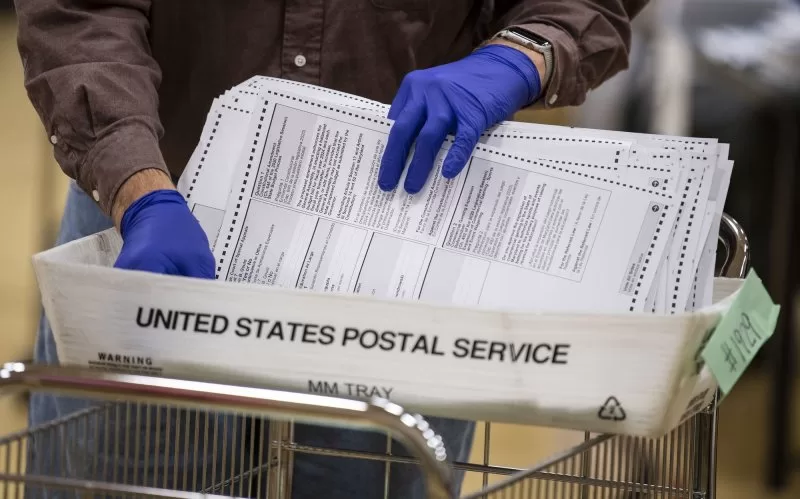

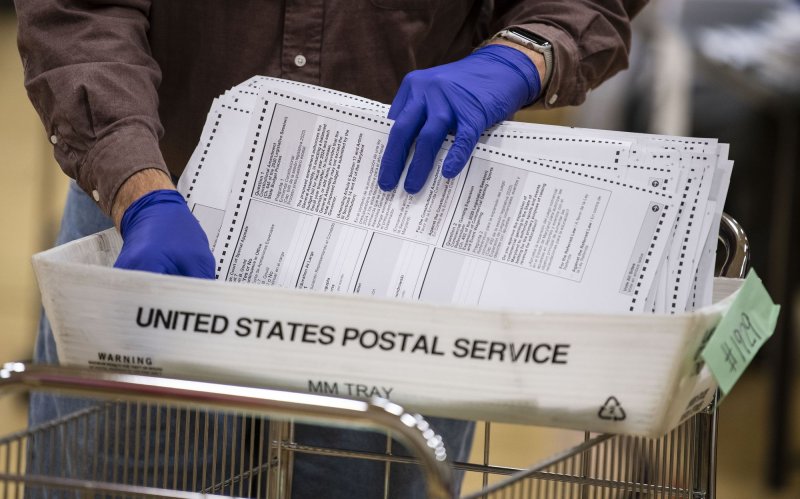

Canvassers process mail-in election ballots at a sorting facility in Gaithersburg, Maryland on Thursday, October 29, 2020. The workers check for authenticity and errors before tabulating the vote. Voting by mail has soared in the run up to the November 3rd 2020 presidential election due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Kevin Dietsch/UPI |

License PhotoAug. 22 (UPI) — Voters in Alabama may face up to 20 years in prison for offering or receiving compensation for assistance turning in a mail-in ballot, according to a new state law.

SB1 makes it a Class B felony to pay or give a gift to a third party to order or deliver an absentee ballot. A Class B felony is punishable by up to 20 years in prison and a $30,000 fine.

Likewise, it is a Class C felony for a third party — with some exceptions — to accept payment or gifts for these purposes. The maximum penalty for this is 10 years in prison.

The state legislature passed the law in March in an attempt to curb “ballot harvesting.” Ballot harvesting is another term used for ballot collecting; third parties gathering and submitting completed absentee or mail-in ballots.

The term is also used by opponents to absentee and mail-in voting.

“Here in Alabama, we are committed to ensuring our elections are free and fair,” Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican, said in a statement. “I commend Secretary of State Wes Allen, as well as members of the Alabama Legislature for making election security a priority, and I am proud to officially sign Senate Bill 1 into law. Under my watch, there will be no funny business in Alabama elections.”

There is no evidence of widespread ballot collecting leading to voter fraud in the United States. It is legal in more than 30 states with varying restrictions.

“We’ve had no documented cases of widespread fraud related to absentee ballot collection,” Rep. Jeremy Gray, D-Opelika, told UPI. “This bill is a solution in search of a problem.”

Gray expects the law to disproportionately affect the elderly, rural voters and those with mobility issues.

There are exceptions to the law. Family members to the second degree like parents, siblings, aunts, uncles and grandparents can offer assistance ordering, collecting or submitting ballots.

Roommates who have lived in the home for more than six months prior to the voter submitting their ballot can also help. Assistance is also allowed if the voter is blind, disabled or unable to read or write.

A coalition of organizations, including the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program and the state conference of the NAACP, has filed a federal lawsuit against the state’s district attorneys and Secretary of State Wes Allen. It describes the law as a “sweeping statute that turns civic and neighborly voter engagement into a serious crime.”

“In doing so, SB 1 criminalizes constitutionally protected speech and expressive conduct and disenfranchises disabled voters, senior citizen voters, voters of color, eligible incarcerated voters, and many other Alabamians who depend on assistance to vote,” the lawsuit reads.

Voters in Alabama vote absentee at very low rates. According to data from the secretary of state’s office, about 3% of votes cast in the 2018 midterms were by absentee ballot. About 13% voted absentee in 2020, compared to 43% nationwide, according to research by Richard Fording, a political science professor at the University of Alabama. In 2022, absentee voting fell back to about 3% in Alabama.

Fording told UPI that this is because the state has some of the strictest requirements for absentee voting. These restrictions were not loosened during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were in other states.

“The state did very little to make voting by mail easier during the pandemic,” Fording said. “In fact, in a state report card on voting by mail accommodations during the pandemic published by Brookings, Alabama was the only state to receive a grade of ‘F.'”

SB1 follows a long history of voter suppression, according to Fording. These efforts have largely targeted Black voters.

“When the sponsor of SB1 claimed that absentee voting rates were unusually high in some counties, he was referring to majority-Black — and majority-Democrat — Black Belt counties,” Fording said.

“This increase in absentee voting was most likely facilitated to some degree by nonprofit groups that provided much-needed assistance with voting during the pandemic. This has nothing to do with fraud. It is simply an effort by the majority party to maintain its monopoly of power in this state.”

Organizations like the Alabama Election Protection Network work to educate voters and promote resources that may help them participate in elections. Melissa Gilliland, project manager of AEPN, told UPI the law was presented in the legislature without justification. She echoed Fording’s observation that it was crafted to disproportionately disenfranchise Black voters.

Gilliland said Alabama’s redistricting plan that was shot down by the Supreme Court last year sought to do the same.

“If you examine the legislature, it is crafting legislation that is making it more challenging to vote,” she said. “They quantify it as ‘protection.'”

Gilliland advises that voters check their registration and polling place. States may remove voters from the rolls up to 90 days before the election but not later than that, according to the National Voter Registration Act.

The AEPN, founded in 2020, links users to official state portals where they can check their registration and polling location. The organization also arranges rides to bring voters to the polls.