Vice presidents seeking the top job almost always feel a need to separate themselves from the presidents they’ve served.

For Hubert Humphrey, the moment came late in his campaign. In a nationally televised speech on Sept. 30, 1968, he called for a halt to the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam, departing from the Johnson administration’s war policy.

George H.W. Bush struggled to establish a distinct identity with voters after eight years as second fiddle to the very popular President Reagan. In his speech to the Republican convention in August 1988, he called for a “kinder, gentler nation” — to which Nancy Reagan famously retorted:

“Kinder and gentler than whom?”

Newsletter

You’re reading the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Anita Chabria and David Lauter bring insights into legislation, politics and policy from California and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Vice President Al Gore faced a problem less acute than Humphrey’s, but more pressing than Bush’s: Most voters in 2000 approved of President Clinton’s job performance, but many disapproved of his personal conduct.

Gore chose a symbolic separation, picking as his running mate Sen. Joe Lieberman, who two years earlier had become the first prominent Democrat to publicly rebuke Clinton for his affair with Monica Lewinsky, calling his actions ‘’disgraceful’’ and ‘’immoral.”

Major points to watch for at the convention

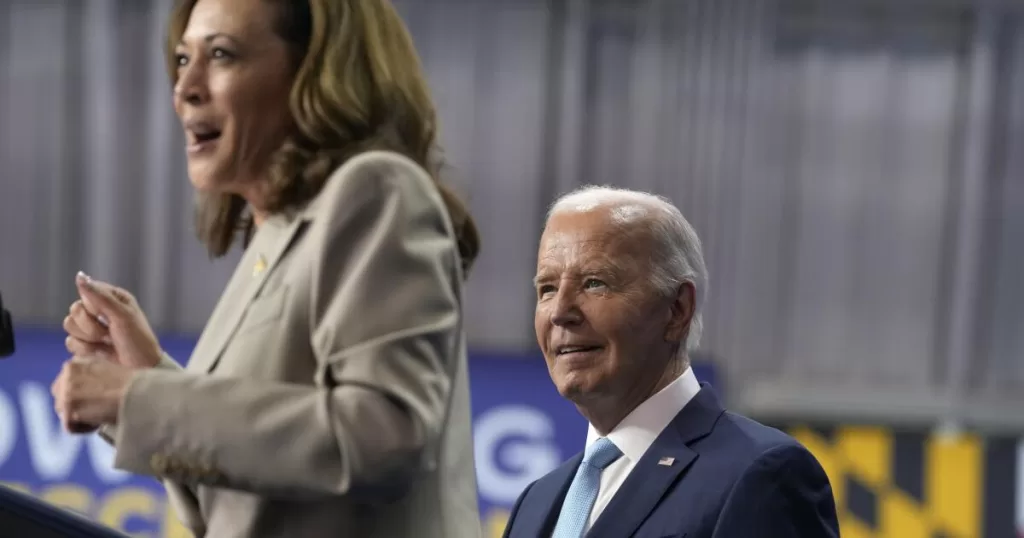

At next week’s Democratic convention, one major question to pay attention to will be the extent to which Vice President Kamala Harris follows the pattern of those previous vice presidents and defines herself by contrast with President Biden.

That’s not the only question mark. Among others:

- How heavily will Harris lean into her experience as a prosecutor? Her law enforcement experience served as a liability during her 2020 primary campaign, but now has reemerged as a political asset. Expect to hear multiple references to it over the course of the week.

- How will she respond to expected protests over U.S. policy toward the war in Gaza? Harris has tried to show more empathy than Biden toward the suffering of Palestinian civilians. But that’s done little to placate protest groups that have called for a full-scale reversal of U.S. support for Israel.

- Which voices in the party will she elevate with prime speaking positions? Convention organizers have said they will feature major voices from the Democratic past, including President Biden and former Presidents Obama and Clinton. The more important question, however, will be which potential voices of the party’s future Harris chooses to highlight.

- How much policy detail will she roll out? Republicans gave the Democrats running room by adopting a platform with almost no policy detail. Harris seems likely to provide more detail while still sidestepping efforts to lock her into potentially controversial commitments.

Big gains among Latino voters

Leading into convention week, Harris has succeeded in uniting and motivating her party. She’s also won over a significant share of less partisan voters who had soured on Biden. That has catapulted her into a small lead over Donald Trump in most national polls and at least a tie in most swing states.

Some of the most striking gains have come among Latino voters, especially younger Latinos who do not hold strongly partisan views. While Biden led Trump by just 5 percentage points among Latino voters in battleground states, Harris leads by 19 points, according to a poll released this week by Equis Research.

The result has been to “reset the race,” back to the levels of Latino support that Democrats had in 2020, said Equis co-founder Carlos Odio. That’s still below what Democrats received in 2008 and 2012, but “far from the apocalyptic levels” that some polls indicated this spring and “enough to win” key states, Odio said.

Harris has been able to win over those voters by appearing as a fresh face while, at the same time, presenting herself as experienced and tested, Odio said.

“To a remarkable degree, she’s been able to pull from the advantages of being an incumbent while also being someone new,” he said. “It’s a tricky balancing act, but so far, it’s working.”

Illustrating that, a poll conducted for the Cook Political Report with Amy Walter found that 56% of voters in battleground states said Harris represents a chance to “turn the page of the Trump/Biden era.”

The survey found that 59% of the voters in the seven battleground states — Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin — said Harris represents “a new generation of leadership,” Walter wrote in reporting the findings.

Shift on immigration

One of the most notable areas in which Harris has tried to define her identity in a way that’s separate from the administration has been on border security, which has been one of Biden’s biggest political weak spots.

Republicans want to hold Harris responsible for the administration’s border policies. They’ve used the border as part of a wider attack on Harris as a “San Francisco liberal” who is soft on crime and disorder. As evidence, they cite the assignment Biden gave Harris early in 2021 to work on the “root causes” of international migration.

Harris hasn’t split with any of Biden’s policies. Instead, she’s countered by trying to focus voters’ attention on a different chapter of her life — her experience as California attorney general and San Francisco district attorney. Campaign ads laud her as a “border-state prosecutor” who “took on drug cartels” and who, as president, “will hire thousands more border agents.”

“Fixing the border is tough. So is Kamala Harris,” a recent ad declares.

That emphasis on border security represents a dramatic shift from the 2020 presidential campaign, in which prominent Democrats talked about decriminalizing the border and abolishing ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

“It’s a 180-degree difference from what the Democratic orthodoxy has been” on immigration, said Mike Madrid, a California-based anti-Trump Republican strategist.

Madrid, author of “The Latino Century,” a new book on Latino politics, believes the approach could help Harris with younger Latino voters who are often two or three generations removed from the immigrant experience.

Whether or not that proves true, it’s clear that Harris’ emphasis on border enforcement has not generated the sort of public protest that might have been expected even a few months ago. That adjustment testifies to how much the party has shifted to match changing public sentiment on immigration issues.

Turning the page

Harris has succeeded so far in part because the unusual circumstances of 2024 have allowed her to turn one of the traditional liabilities of the vice presidency — its obscurity — into an asset.

Voters don’t hold Harris fully accountable for Biden administration policies they dislike, said Evan Roth Smith, a Democratic pollster who leads Blueprint, a Democratic message-testing project.

That’s especially the case on foreign policy, which voters traditionally see as a realm dominated by the president, but it also holds true on other issues, including economic policy and the border, Blueprint polling has indicated.

“Voters’ attitudes toward Harris are far less calcified” than their views of either Biden or Trump, Roth said in a briefing for reporters Thursday.

Political science research points in the same direction.

In early August, political scientists Joshua Kalla of Yale and David Broockman of UC Berkeley tested 35 different political messages to see which had the greatest impact on how voters judged the race.

For all the attention that Democratic vice presidential nominee Tim Walz has gotten by labeling Trump and his allies as “weird,” an attack framed around that idea did very little to shift voter opinions, they found.

Indeed, none of the messages that attacked Trump, whether it was about his involvement in the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol or his position on abortion, showed much potential for changing voters’ minds.

“Voters have been hearing about Donald Trump for almost 10 years now. If they’re willing to vote for him based on that near-decade of experience, a few ads or a new quip are unlikely to change their minds about him,” the pair wrote in describing their research.

The messages that did show potential for moving voters were ones that responded to voters’ curiosity about Harris by explaining where she stood on major issues, they found.

That’s why both sides in the campaign are investing huge resources in the competition to define Harris’ image for voters.

So far, Harris has had a big advantage because the news of the last month has centered on her, allowing her message to dominate coverage. With the convention, she’ll likely enjoy that advantage for at least one more week.

The Harris campaign has been seeking to take maximum advantage of that spotlight while they have it. In the race to define how voters see the vice president, luck has given them a head start.

The election likely will turn on how effectively they can use that time to build up Harris’ image before the expected Republican onslaught starts to tear it down.

What else you should be reading

Poll of the week: Mexican views of the U.S. have become more positive even as U.S. views of Mexico become more negative.

Saturday must read: Are Black voters really leaving Democrats in the dust? Data from recent elections tell a more complicated story.

L.A. Times special: Adam Schiff expands already sizable lead over Steve Garvey in California Senate race, a new L.A. Times/UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll finds.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox.