When Kiribati broke ties with Taipei in 2019, it was a blow to Taiwan, despite the Pacific island nation’s small stature on the international stage.

Taiwan had already lost six diplomatic allies to China in the years prior, including, just days earlier, the Solomon Islands, as Beijing stepped up its efforts to isolate the self-ruled democracy that it claims as its own.

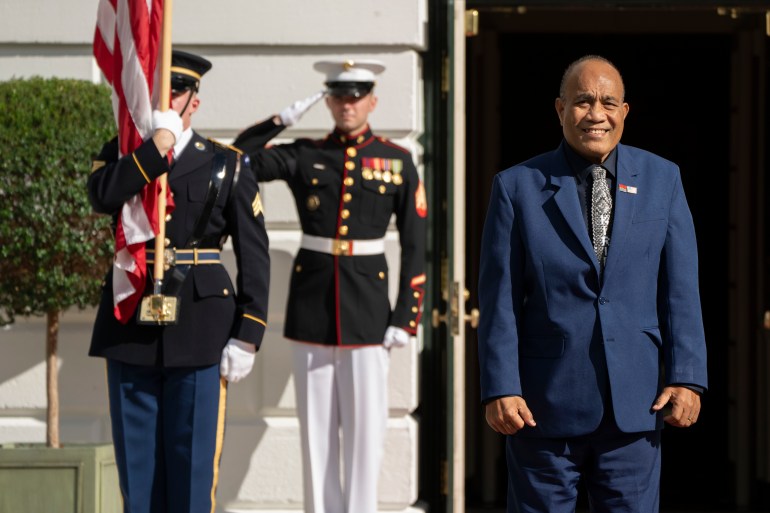

Kiribati President Taneti Maamau’s decision to switch allegiance was also controversial at home, causing a rift within his own government and costing him his comfortable parliamentary majority in a fiercely fought election in 2020.

Senior figures in Kiribati, a low-lying atoll nation of about 130,000 people, feared a lack of transparency around Maamau’s relationship with China, which has previously formed debt-laden relationships with developing countries under its Belt and Road Initiative.

Five years since the switch, as Kiribati heads to the polls again, those fears persist following a turbulent period which has seen strained relations with Pacific neighbours, tensions with traditional ally Australia and a continuing constitutional crisis.

Banuera Berina, Maamau’s ally-turned-rival, who was his main opponent in 2020’s presidential election after splitting from the ruling Tobwaan Kiribati Party (TKP) over concern about its dealings with China, told Al Jazeera the relationship was “not healthy for the country”.

“Transparency is of paramount importance, which unfortunately is lacking in our government now,” said Berina, who is standing again as a parliamentary candidate, but does not plan to run for the presidency again.

While domestic issues such as the cost of living are set to dominate parliamentary elections this week and next, international observers will also be “watching closely” for any insight into the presidential elections later this year, according to Jessica Collins, a Pacific aid expert at the Lowy Institute.

“There’s a lot at stake. If the people vote for change, President Maamau may not get re-elected later in the year, frustrating China’s ambition and curtailing its successes,” she told Al Jazeera.

“If parliament – and later in the year the president – remains largely the same, Australia will have its work cut out trying to remain a valued and welcome partner,” she added.

‘Hoping for a reset’

On Wednesday, 114 candidates were contesting 44 seats in Kiribati’s parliament, Maneaba ni Maungatabu. A second round of voting is scheduled for August 19 to decide seats where no candidate has secured a majority.

Although political alignment is often clear, parliamentary candidates in Kiribati officially stand without party affiliation. Those elected to parliament then choose at least three candidates to be put forward for a presidential election, which is expected to take place in October.

Rimon Rimon, a local investigative journalist, said it was hard to gauge the mood in Kiribati because “people live in a landscape of fear”. But he said the vote would offer a “preview of what the people want” ahead of the presidential election.

While Rimon believes many people sense the governing party “has not been honest in their promises”, in a political system dominated by personal patronage over party affiliation, “well-resourced” government-aligned candidates might have the edge over the opposition.

“I think this whole election process is going in favour of the ruling party,” he told Al Jazeera.

A strong showing at the parliamentary elections for government-aligned candidates would boost Maamau’s campaign for a third successive presidential term, but some observers, like Rimon, worry about the consequences for Kiribati’s democratic future.

The past four years under the TKP have been among the most turbulent in Kiribati since the country gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1979.

In July 2022, Maamau withdrew Kiribati from the Pacific Islands Forum, citing his belief that the body, which plays a key role in regional cooperation on issues including security, economic development and climate change, was not serving his country’s interests.

While Maamau rejoined six months later, Kiribati’s opposition feared China played a role in the initial decision, suggesting that Beijing would benefit from an isolated Kiribati, not least in terms of security and exploiting the country’s fisheries. Beijing said the claim was “groundless”.

Kiribati is tiny but strategically significant. The closest of its 33 islands and atolls is just 2,160km (1,340 miles) south of Honolulu on the United States island of Hawaii.

China has promised to help Kiribati achieve KV20, a 20-year development plan launched by Maamau and structured around fishing and tourism. As part of that it has said it will help rebuild a World War II US military airstrip on Kiribati’s Kanton Island, which sits roughly halfway between Hawaii and Fiji.

In February, the Reuters news agency, citing the acting police chief, reported that Chinese police officers were working in Kiribati, taking part in community policing and a crime database programme under an agreement that has not been made public.

Kiribati also boasts one of the largest exclusive economic zones in the world, covering more than 3.5 million square kilometres of the equatorial Pacific – a pristine marine region roughly the size of India. The 2021 scrapping of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, one of the world’s largest marine reserves and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has resulted in “Kiribati now hosting too many Chinese fishing vessels”, Berina said.

As ties have warmed with Beijing, Kiribati’s relations with traditional ally Canberra have cooled. Australian officials have reported that their visas have been denied or delayed, while a bilateral strategic partnership agreement, already a year overdue, has been put on ice indefinitely.

Blake Johnson, Pacific analyst at the government-funded Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), said the past four years had “seen the relationship between Australia and Kiribati decline” but that Canberra would be “hoping for a reset” even if Maamau got a third term.

“I would expect the Australian government to invest more time and effort into rebuilding that relationship,” he said.

‘No politics, no ideology’

Last May also saw judge David Lambourne, an Australian national who served in Kiribati’s High Court, forced out of the country following a years-long saga that has thrown the judiciary into crisis.

Maamau’s government first levelled charges of misconduct against Lambourne – a resident of Kiribati for three decades and husband of opposition politician Tessie Lambourne – in 2022. That year, attempts to deport Lambourne were deemed illegal by Kiribati’s Court of Appeal, composed of members of New Zealand’s judiciary.

Thwarted by expatriate judges, which have long formed the backbone of Kiribati’s high courts, Maamau’s government suspended Chief Justice William Hastings and the Appeal Court judges, causing the country’s judicial system to grind to a halt.

A senior source with close knowledge of Kiribati, who requested anonymity due to fears over his security, told Al Jazeera that the saga “completely compromised” the judiciary. The source added that “respect for democratic norms has deteriorated to such an extent that I don’t think it can be denied that the president is an autocrat”.

The source continued that the case against David Lambourne was a “blatant attack on the opposition” given his marriage to Tessie Lambourne, who is widely viewed as having the best chance of unseating Maamau in the presidential race.

While he did not think Beijing was providing explicit instructions to Maamau, the source said, “their interests certainly align” in wanting to “unseat Tessie Lambourne if they possibly could”.

“I imagine there are people in Beijing who would not want to see a change of government in Kiribati,” the source added.

A spokesman for President Maamau said he was not able to answer questions before publication. The Chinese embassy in Kiribati did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment however, ahead of the polls Ambassador Zhou Limin praised Maamau’s government and its “historic achievements in various areas”.

Einar Tangen, a senior fellow at the Taihe Institute in Beijing, paints a more benign and pragmatic picture of China’s relationship with Kiribati. He says the accusations of malevolent Chinese influence in Kiribati are part of the “same playbook” used by the US and Australia to discredit Beijing in other parts of the Pacific, and curtail its influence.

“There’s no politics [in the relationship], there’s no ideology. Kiribati has asked for help, and China has offered it,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Kiribati is not interested in the international politics of the US and China. They’re interested in food. They have one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the area and they’re trying to get on with their life. If somebody offers them more aid, they’re going to take it.”

‘An uphill battle’

Whether China is helping or not, several observers told Al Jazeera that the scales in the election appear tipped in the ruling party’s favour – not least in terms of financial resources.

Money, an important commodity in any election, becomes even more influential in a system in which ideology and party affiliation come second to personal patronage.

The anonymous source pointed to Tessie Lambourne’s constituency, the island of Abemama.

With two parliamentary seats up for grabs, Lambourne is competing against the current Minister for Infrastructure and Sustainable Energy, Willie Tokataake, and a previously unknown local school teacher, who has been “an extremely generous benefactor in the lead-up to the elections”.

While he cautioned that it was impossible to know for sure, the “generally understood view is that this money almost certainly originated in China and has been funnelled to him through the president’s political party”.

Journalist Rimon says several candidates have “raised eyebrows” because they are “splashing a lot of cash and giveaways for people”. “You just wonder, where are they getting all these resources? Why do they have so much money?” he said.

Berina alleged that when he was a TKP member, President Maamau promised that he and other parliamentarians would be “given money by China in order to retain our seats”.

Similar allegations were made in the last round of elections in 2020, with Maamau denying he received any financial support from China.

“There wasn’t any involvement especially in funding by the Chinese government,” he said in a rare interview with the media following his re-election.

China denies that it interferes in the internal affairs of Pacific nations.

Following a failed attempt to establish a Pacific-wide trade and security pact in 2022, Foreign Minister Wang Yi said China had “never established a so-called sphere of influence” and has “no intention of competing with anyone”.

Either way, Rimon believes Lambourne faces an “uphill battle” in this election. “She is on the top of the government’s list to try to eliminate, because if she doesn’t get re-elected in Abemama, that’s the end of [her presidential challenge],” he said.

From Beijing’s perspective, Collins of the Lowy Institute points to Lambourne’s “Australian connection” and her “deployment to Taiwan”, where she was Kiribati’s ambassador in 2018-19, as reasons for their possible concern.

“It’s possible for a Pacific nation to re-establish diplomatic relations with Taipei – a move that would grate against China given its reward-like investments in Kiribati when it switched allegiance to Beijing,” Collins said.

Berina, for his part, said he will support any opposition candidate, including Tessie Lambourne, given his “grave concerns” over Maamau’s closeness with China.

“The danger lies in the fact that we are being made to walk in the dark,” he said. “And in the dark, you can never know the kind of danger lurking therein.”