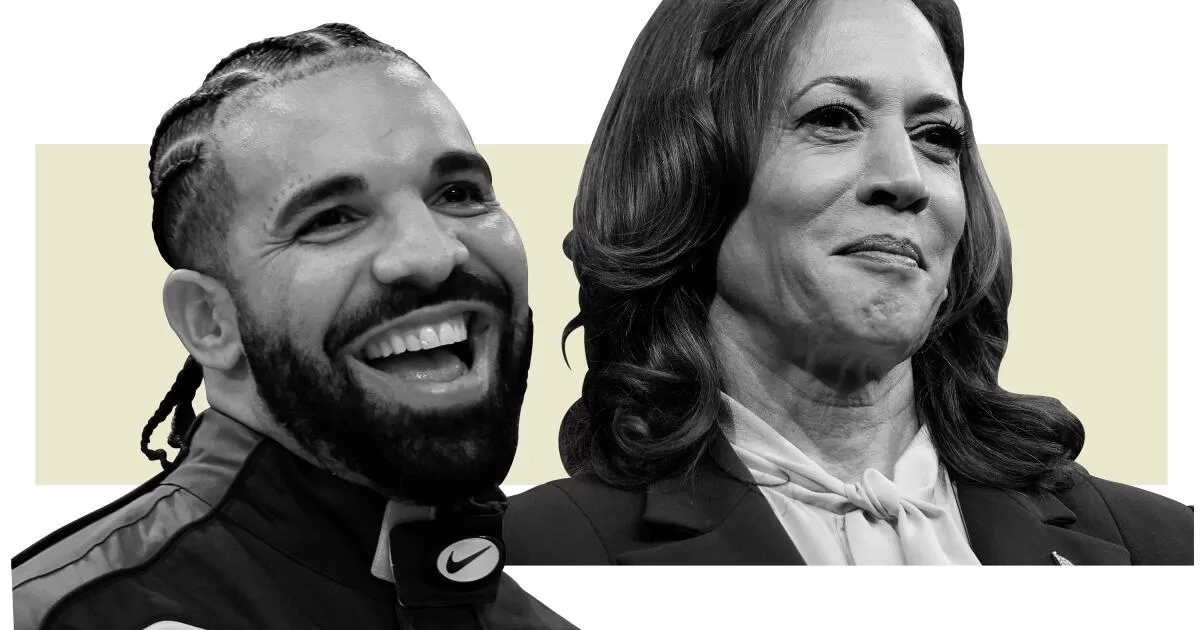

On the same day that former President Trump claimed before a national gathering of Black journalists that Vice President Kamala Harris “was Indian all the way, and then all of a sudden she made a turn, and she became a Black person,” his running mate Sen. JD Vance accused Harris of being a “phony” who “grew up in Canada” (she attended high school in Montreal) and used “a fake Southern accent” at a rally.

Both men’s accusations sound eerily like those leveled against the rapper Drake by his fellow hip-hop titan Kendrick Lamar (and many others) in a rap beef whose effects linger. Drake has been accused of being a “colonizer” whose Canadian identity and eager embrace of various aspects and accents of a wide range of Black culture make him racially suspect.

Such arguments, whether made by racially troubled white men or Black icons, deny the complexity and diversity of Blackness.

Trump and Vance have little understanding of and less respect for the multiracial strains and complicated cultural mixtures of Black identity. Harris has from the start acknowledged her Indian heritage and her Jamaican roots. In our national context, biracial Blackness has always covered a multitude of skin types, light or dark, Caucasian or Indian and lots more besides.

Millions of Black Americans, because of the history of slavery conservatives tend to ignore, have all sorts of ethnic blood in their veins and all sorts of figures in their family trees — a grandfather who was Native American rests on one branch, a great grandmother who was Irish on another.

The one-drop rule of Black identity reflects the compulsion to reduction in American racial politics: Each body genetically shaped by white and Black ancestors has been viewed as tainted and inferior and labeled as Black. The same is often true for Black bodies mixed with Latinx and Asian identities.

Nonetheless, many mixed-race folks proudly tout their one-drop Black identity. Harris’ Indian mother understood she was rearing Black daughters, however often they dressed in saris and visited India. Like millions of Black folks, she understood Blackness’ diverse expressions.

Trump’s argument that Harris pivoted from her Indian to her Black identity also flies in the face of the facts of Harris’ biography, her education at Howard University and her affiliation with the Black sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha. Trump’s narrative that Black people pimp their race for social gain appeals to those who believe that Black progress comes at the expense of white prosperity. Vance’s vacuous turn of phrase reflects his faux shrill-billy white resentment of Harris’ cosmopolitan Blackness.

Ironically, that cosmopolitan vision of Blackness is at the heart of the Lamar and Drake dustup. Their kerfuffle — playing out fiercely this spring in a series of releases — is a battle over cultural cachet, racial authenticity and group pride. And it exposes a provincialism that undercuts the global currents of hip-hop.

In his hit “Not Like Us,” Lamar accuses Drake of being a “colonizer” because Drake supposedly “run[s]” to Atlanta to partner with some of the paragons of its trap music to bolster his Blackness. Lamar’s argument echoes long-standing criticisms that Drake’s biracial Canadian roots render him suspect as a bona fide Black artist. Drake’s artistic experimentation with different accents and musical genres has prompted many to claim, as Vance did with Harris, that Drake is a phony.

Lamar’s beef with Drake is rooted in a parochial, claustrophobic vision of Blackness.

Drake grew up in Toronto the son of a Jewish Canadian mother; he spent summers in Memphis, Tenn., with his Black American musician father. His artistic tastes were deeply influenced by a wide swath of the Black diaspora — Afro-Caribbeans, Londoners, American Southerners, especially Memphians, and Torontonians. The multicultural makeup of Toronto, with its sizable Italian, Portuguese, Jamaican and Filipino immigrant populations, also fed his musical appetite.

The argument that Drake is somehow a culture vulture who appropriates varieties of Black culture misunderstands not only his influences but hip-hop as an art form with universal reach. Drake’s critics seek to confine it, and Black culture in general, to the United States, which received far fewer Black folks in the slave trade than, say, Peru, Mexico, Brazil and Jamaica.

Oddly enough, the attempt to define him as a colonizer overlooks how Black people in the United States often believe that our Blackness is superior to that of other Black people, itself a colonial view that is far more problematic than anything of which Drake might be accused. And given that Canada offered a prominent pathway to freedom for those who escaped American slavery, it is utterly bizarre to paint Drake as somehow alien or an enemy of hip-hop because he is Canadian and not from Compton or Detroit.

At a Trump rally in Charlotte, N.C., a white female commentator sought to remind Black Americans that Harris “is not one of you.” Lamar’s “Not Like Us” is unfortunately propelled by much the same limiting racial logic. As we fight to expel the racially troubling ideas and mischaracterizations Trump and Vance voice about Kamala Harris, Black folk must be careful not to permit those very same ideas in through the back door of our culture.

Michael Eric Dyson is a professor of African American studies at Vanderbilt University and the author, most recently, of “Entertaining Race: Performing Blackness in America.”