Over five years ago, the Borno state government commissioned an industrial hub and a solar panel manufacturing plant as part of an ambitious plan to revive the state’s economy.

Since 2009, when the Boko Haram terror group started waging a war against the country, persistent conflict in northeastern Nigeria has led to the loss of lives and properties, the destruction of critical infrastructure, the displacement of millions of people, and the destabilisation of health and education systems. These developments have adversely affected the region’s economic growth.

Mamman Ari is one of the countless youths in Maiduguri, the state capital, whose lives have been upended by the conflict. Once gainfully employed, riding a commercial tricycle for a small cut of the weekly earnings, Mamman’s world turned upside down when the owner sold the vehicle. Desperation set in as he jumped from one fleeting job to another, each one a dead end.

Before the insurgency, Mamman was a farmer in his village in Mafa local government area. His farmland, once a source of sustenance and pride, is now a dangerous no-go zone controlled by Boko Haram terrorists. His hopes for a stable life have been dashed, leaving him trapped in a cycle of uncertainty and fear.

Mamman, a husband and father of two, faces an agonising decision. With no opportunities left in Borno, he contemplates a heart-wrenching move. “My friend has promised me a position in a factory in Lagos,” he revealed. “I have no choice but to leave my family behind. There’s nothing left for me here.”

The Boko Haram insurgency has exacted a devastating toll on northeastern Nigeria, claiming the lives of over 40,000 people and displacing millions from their homes. The conflict’s economic impact is equally immense, with Borno state alone suffering $5.9 billion in damages as of 2019, according to the World Bank.

Former Borno Governor Kashim Shettima, now Nigeria’s Vice President, launched the industrial hub in April 2019, envisioning it as a catalyst for the state’s economic recovery.

“Believe me, in the coming months and weeks, we will start the real Borno renaissance project, and the whole world will be surprised by what we are going to reveal,” he said during a 2018 interview, roughly a year before the project was commissioned.

The industrial hub was intended to include various food processing factories, such as those for tomatoes, ginger, and onions. Yet, four years after its establishment, the project has failed to provide opportunities to the millions of unemployed youth in the state. Budget documents from 2015 to 2023 reveal zero earnings from the industrial hub. This failure is particularly disheartening for the local community, where hardship is rife.

The industrial layout is located at Njimtilo village, opposite the Borno State University. Our reporters could not access the premises due to the heavy presence of military personnel on the route. However, the factory is visible from the roadside opposite the military checkpoint at the entrance to Maiduguri. As you approach the town, you can see the net houses used for planting tomatoes from a distance.

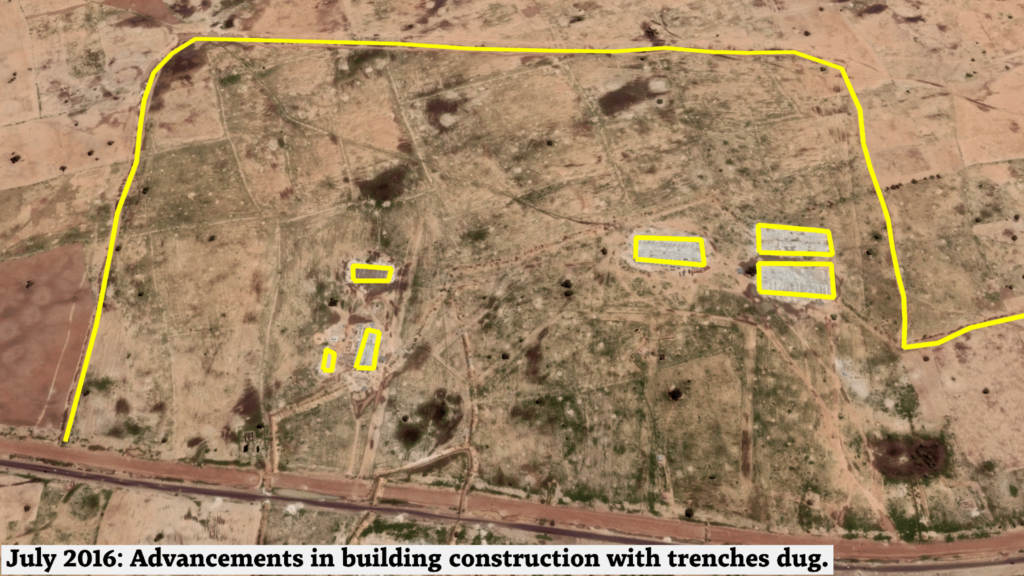

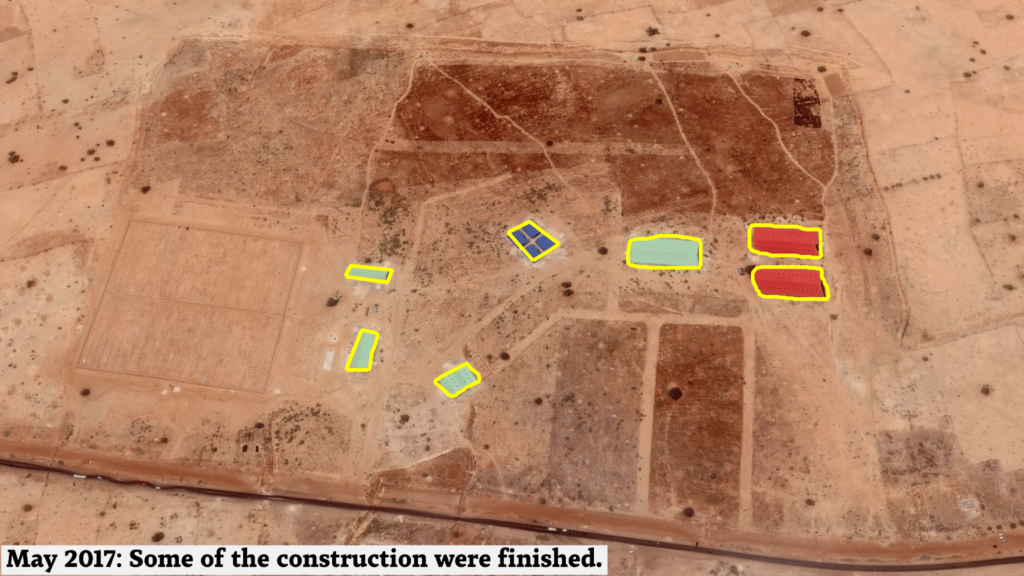

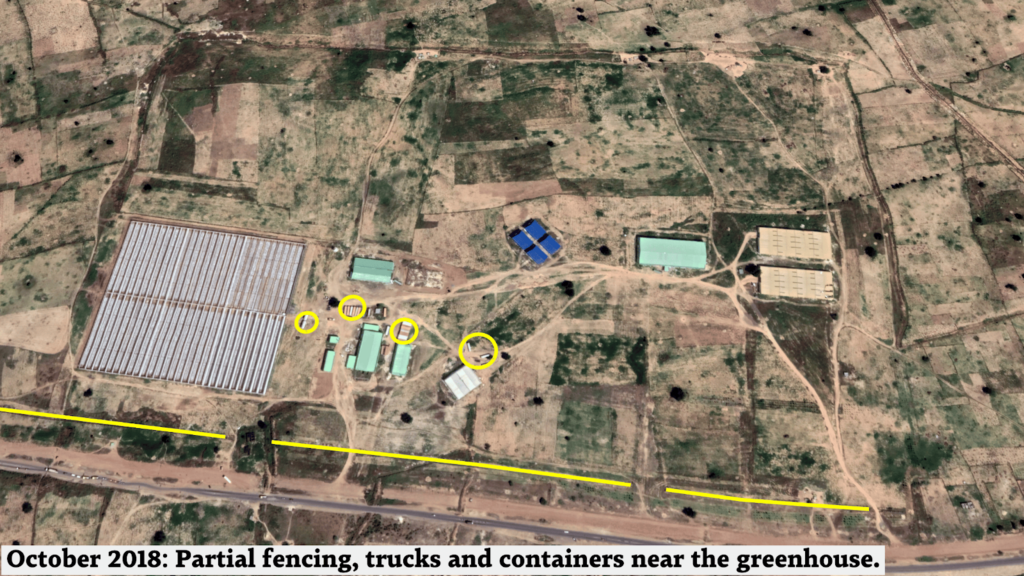

Meanwhile, an analysis of satellite imagery revealed that construction work on the land started around July 2016. The buildings were completed and roofed in May 2017. Months later, a greenhouse was constructed. Trucks used for supplies and equipment transport appeared around this time, eventually becoming stagnant and rusted due to little use.

No significant activity has been detected at the site since October 2020, strongly suggesting abandonment. This assessment aligns with recent imagery from July 2024, which reveals unchecked vegetation overgrowth and deteriorating infrastructure.

The industrial hub comprises 19 diverse processing and production facilities. These include plants for solar panels, waste recycling, tomato and cassava processing, ginger and onion dehydration, table water, juice, corn chips, biscuits, drip irrigation pipes, plastic mats, school desks and chairs, PVC pipes, canopy shades, and sacks.

It was said that the solar panel manufacturing plant — wrongly touted as the largest in Africa — could produce panels capable of generating 120 megawatts annually. Additionally, the plant would generate electricity for the state, addressing the power outages caused by Boko Haram attacks on power lines.

The primary school desk and chair manufacturing plant was also expected to provide the necessary furniture for the state’s ‘mega’ schools.

“The solar industry in Borno has enormous potential,” said Abba Kabir*, a local solar panel seller and installer who asked that his real name not be published. “If the plant becomes operational, it will not only provide affordable solar panels but also create job opportunities for many young people in the region.”

Kabir emphasised that the current challenges faced by the local solar industry, including high costs and limited availability of quality panels, could be addressed if life was breathed into the plant. “Most of our panels are imported, making them expensive for the average household. A local plant would drastically reduce costs and make solar energy more accessible,” he explained.

He further noted the importance of government support in promoting renewable energy.

“The government needs to ensure the plant is fully operational and support initiatives that encourage the use of solar energy. This would help reduce the reliance on traditional power sources and improve energy security in the state.”

The drip irrigation pipe manufacturing plant aims to modernise irrigation farming and boost the supply of raw materials for the agro-allied plants within the industrial hub. Most of the 16 plants in the cluster are agro-allied, so they will depend wholly on agricultural products sourced from the surrounding farming communities.

Traders and farmers at the Gamboru Vegetable Market, however, expressed their disappointment and ignorance about the tomato processing plant’s existence. Farmers lamented the loss of their perishable goods, which could have been saved had the plant been operational.

Abba Massa, a tomato farmer from the Gamboru vegetable market, vividly remembers the optimism that surrounded the commissioning of the industrial hub. “In 2019, we were told that we wouldn’t have to worry about our farm produce rotting and that the tomato processing plant would change our lives. We saw sample cans of tomato paste,” he said.

However, today, Abba and many like him still have the same challenges.

“I lost half of my harvest last season because there was nowhere to process the tomatoes. It’s heartbreaking to see our hard work go to waste, and this happens every year,” he cried.

A provision seller laughed when shown the image of the Borno tomato paste. He said, “I have never seen or heard of it anywhere; this is just Photoshop. If any tomato paste was produced in Borno state, I would certainly know of it.”

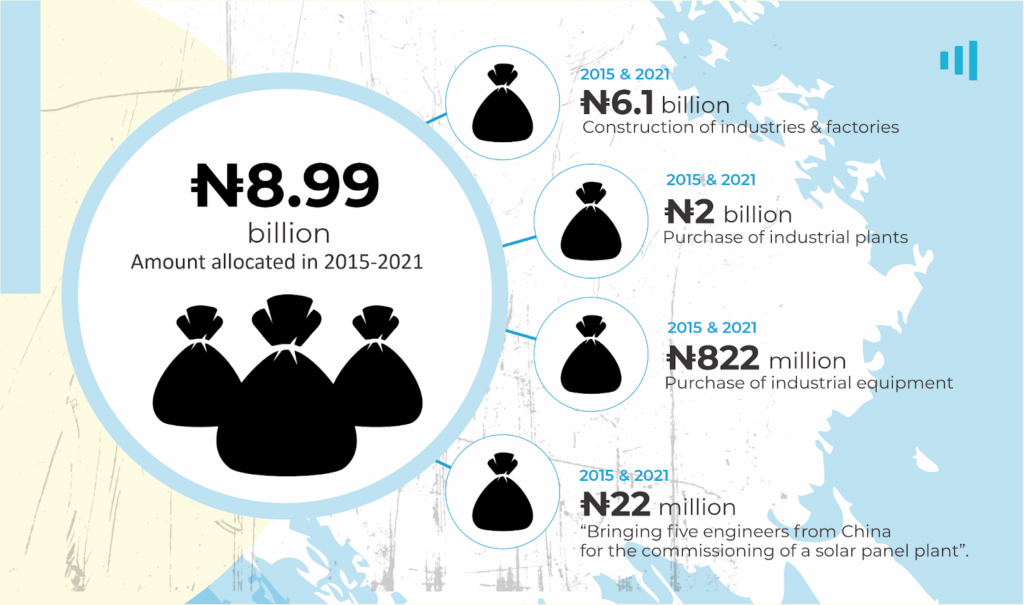

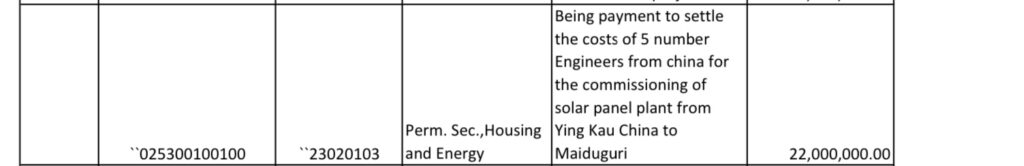

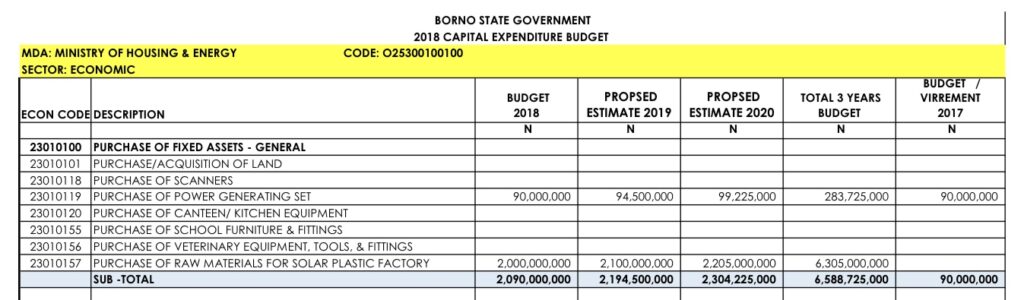

The establishment of these projects was done through a private-public partnership (PPP) arrangement. A study of budget documents between 2015 and 2021 showed that the state government may have allocated up to ₦8.99 billion towards their completion. Within this period, the government approved and/or spent the sum of ₦6.11 billion for the construction of industries and factories, ₦2.05 billion for the purchase of industrial plants, ₦822 million for the purchase of industrial equipment, and ₦22 million to settle the costs of bringing “five engineers from China for the commissioning of a solar panel plant”.

Also, back in 2014, millions of naira were similarly allocated to the Ministry of Trade, Investment, and Tourism to establish various mills, factories, and industries. It was earmarked ₦250 million for Borno Plastic Company (BOPLAS), ₦250 million for a soda ash company, ₦200 million for a tomato and pepper processing company in various local government areas, ₦60 million for a groundnut oil processing mill in Gubio, and so on.

HumAngle wrote to the Ministry in June for comment about the status of the industrial hub and solar panel factory, but we have yet to receive a response.

Historically, the locals have relied heavily on crop and livestock farming, fishing, and trade. The introduction of agro-allied businesses, such as food processing factories, aims to elevate the region’s economic status by fostering productivity up the value chain.

Before the onset of the Boko Haram insurgency, Nigeria’s northeastern region, with Borno as a focal point, engaged in substantial cross-border trade, primarily through Maiduguri. Farmers, traders, transporters, and fishermen from the Lake Chad Basin region—comprising Cameroon, Chad, and Niger—depended on Maiduguri as a vital trade hub. The insurgency, however, disrupted this economic lifeline, causing severe setbacks.

The industrial hub project aimed at a bold and ambitious response to these economic disruptions. Since the conflict began, total trade between Nigeria and its neighbouring countries—Cameroon, Chad, and Niger—has declined by over 70 per cent. This sharp reduction has severely impacted the income of businesses and households. In 2021, the Borno Fish Producers and Marketers Association reported losing ₦500 million weekly due to decreased trade volumes. Consequently, many businesses have relocated to other states within Nigeria, resulting in significant job losses and decreased vital income sources.

Given these challenges, the state government’s 25-year development plan focuses on revitalising the local economy by establishing an industrial hub. Promoting agro-allied businesses and setting up food processing factories aims to generate employment, boost economic growth, and reduce the community’s susceptibility to insurgent influences.

When the hub was launched in 2019, Dr Mohammed Musa of the University of Maiduguri’s Economics Department told Daily Trust its survival would depend on several conditions.

“Most of the 16 plants in the industrial hub are agro-allied, relying entirely on agricultural products from nearby farming communities. This means that secure conditions are essential for these communities to ensure a steady supply of raw materials for the industries. Additionally, there must be security along all roads leading to the hub and its markets,” he said.

“The viability of the hub will depend on how well its operators are committed to building and maintaining the infrastructure for optimum performance. This is followed by such key requirements as sufficient electricity, water supply and safe transportation for the raw materials to the industries and the manufactured products to the markets.”

It unclear if the absence of some of these factors contributed to the project’s abandonment.

Comrade Yusuf Ibn Tom, chairman of the Borno State wing of the National Youth Council of Nigeria (NYCN), commended the project at the time, saying it had the potential to trigger positive developments across various industries, which could then employ millions of young people.

“The government that established this cluster must ensure that right from the onset the industries commence operation on a sound footing by ensuring that civil servants hands off the industries because industries are not government parastatals,” he warned.

“[A] Board of Directors should manage these industries without any interference whatsoever from the government so that the government can hold them responsible in the event of failure.”

Youths across the state have shown dissatisfaction with how the hub has been forsaken.

“Youths are jobless in the state. The only work available for the youths is commercial tricycle riding, bread selling, and scrap metal selling. Now, scrap metal selling is banned, and people are not building houses like before, so there are few construction jobs,” said Garba Mai Dawa, a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) and traditional medicine seller.

Mala Isa, an unemployed graduate of Computer Engineering, told HumAngle that if the economy of the region does not improve, it could make it fertile for the growth of even more violent groups.

“It is a shame that existing companies are no longer functioning in the state, and now the newly constructed ones are not functioning either. I am afraid that if the state continues this way, another Boko Haram will emerge in the future,” he said.

Borno State Governor Babagana Zulum has recently announced plans to revive the state-owned tomato factory along the Maiduguri-Damaturu highway.

During a visit to the factory in late July, Zulum declared that the state would resuscitate the existing facilities at the factory and procure additional modern equipment to enhance its operational capacity. In preparation for reviving the factory, he noted that the state has established five hectares of drip-irrigated tomato farms, which will be expanded to about 100 hectares when full-capacity operations begin.

“My main intention is to resuscitate the moribund factories at the Borno industrial park, particularly the tomato paste factory. I understand the challenge is the lack of raw materials to provide feedstock for the tomato factory,” Zulum said.

He added that the government will be establishing a “robust” drip irrigation system using net houses to produce tomatoes.

“I am happy to note that we are working under a public-private partnership to establish at least a minimum of 100 hectares of tomato plantation,” he disclosed.

“You can see we started with five hectares, and because of the variety of tomatoes we produce here, each hectare will yield about 60 tons. When we expand to 100 hectares, we will get nothing less than 6,000 tons.”

OSINT analysis by Mansir Muhammed.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.