You don’t interview Antonio Villaraigosa so much as you turn on an audio recorder, sit back and watch a show unfold.

The anecdotes rushing out of his mind like the Los Angeles River after a storm. The answers interrupted by the genuine greeting he throws to the inevitable lookie-loos who glance at the former mayor of Los Angeles and speaker of the Assembly. His ringing, carefree laugh mixed with soaring rhetoric about democracy, working families and hope.

To see Villaraigosa in action is to watch a true political master at work, someone who loves the journey as much as the destination. And Californians will get a front-row seat for the next two years.

Thirty years after winning his first election, the Eastside native is back in the political saddle again, this time out of the gate early in the 2026 race for California governor. Villaraigosa is trying to distinguish himself from the other major Democrats who have announced so far — Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis, California Secretary of Education Tony Thurmond, former state controller Betty Yee and state senator Toni Atkins — by running from the “radical center,” which he has long described as a magical place where everyone comes together to fix the Golden State better than the Right or Left can do on their own.

“In a world where there’s so much deadlock,” Villaraigosa said halfway through our one-hour lunch at La Parrilla in Boyle Heights last week, “it’s radical to put strategies together to break the deadlock and move ahead.”

There are few deadlocks in Sacramento, where Democrats have a supermajority in both chambers of the Legislature and a Republican hasn’t held statewide elected office in over a decade. Villaraigosa seems to be banking on his main opponents running as wokosos in a state where Democratic voters are complaining about crime, homelessness, the cost of living and massive inequities while not trusting the status quo to solve anything.

“When I started out, let’s be honest — I wasn’t as much of a practical problem solver,” he said. “But over time, you realize if you want to get things done and you want to do big things, you got to work with people, including people that don’t agree with you.”

La Parrilla, a longtime favorite for Eastside politicians, was my request. I wanted a place with great food where I could see him in action in his political homeland. That happened the moment he walked in and every single diner stopped what they were doing.

“¡Cómo estás, jefe!” he proclaimed to server Erick Gabriel.

“¡Cómo está, Mr. Garcetti!” the 29-year-old Boyle Heights resident cracked.

“Pegándole duro,” Villaraigosa replied, his voice a tad hoarse after a day working the phones that netted him over $1.5 million. Hitting it hard.

Server Ana Boror came over to hug him.

“You used to have parties here all the time,” she kidded him in Spanish. “You came here often.”

“But I now live far away,” Villaraigosa pleaded, like a Chicano Dennis the Menace.

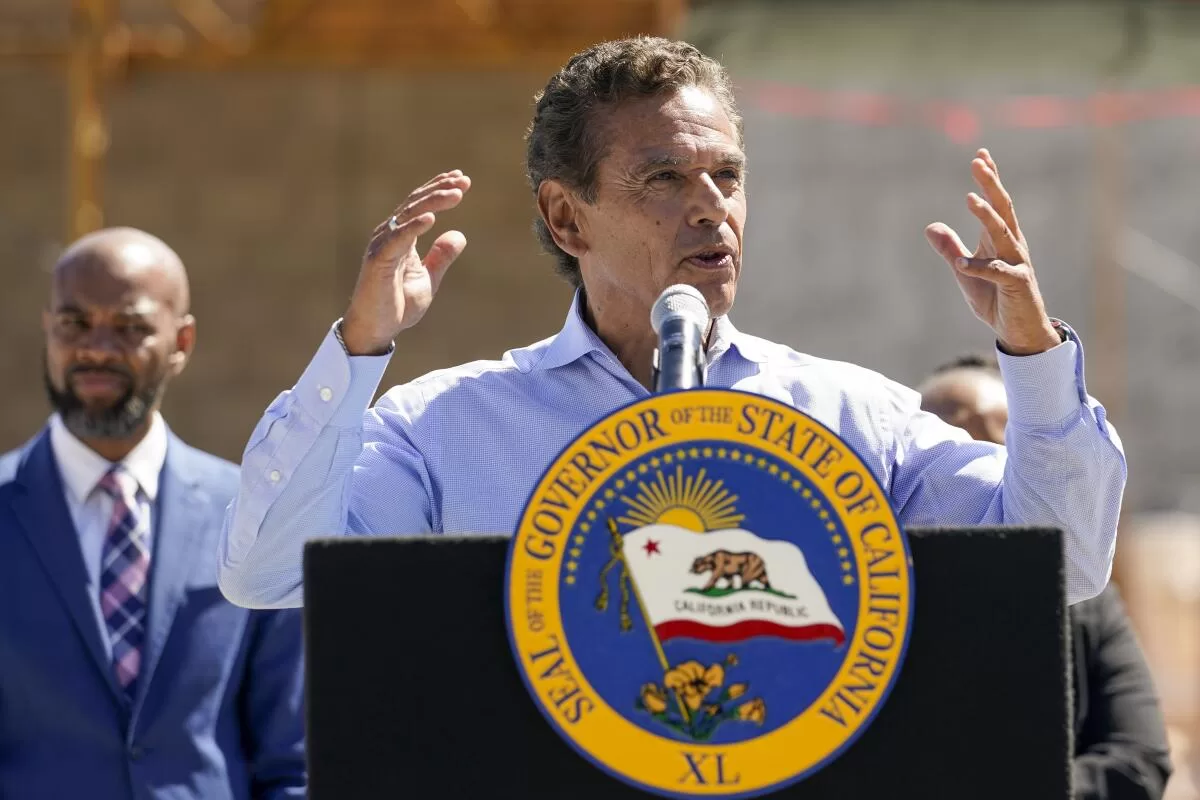

Former Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa talks to reporters during a news conference at the construction site of a new water desalination plant in Antioch, Calif., in 2022, as part of his duties as Gov. Gavin Newsom’s infrastructure advisor.

(Godofredo A. Vásquez / Associated Press)

He asked about the photo of him that used to be near the entrance. I spotted it right above his head in our corner booth: he was deciding between beef and chicken fajitas during a staff party for his historic 2005 mayoral victory.

I asked how today’s Villaraigosa was different from that Villaraigosa.

“You mature over time,” he said. “You’re a little humbler. You lose a few times, and you learn humility. But I’d rather talk about what’s the same.”

He proceeded to uncork a lifetime’s worth of Eastside memories in five minutes as we enjoyed our appetizer of macaroni soup.

“It’s a place of people who are salt of the earth,” he concluded, moving on to guacamole that he spiked with La Parrilla’s salsa de chile de árbol. “And, you know, kind of like, ‘Local boy [made] good,’ you know? To a lot of the residents.”

He stopped to watch a La Parrilla worker pour a giant jug of Jamaica into a percolator.

“With caution!” he advised loudly in Spanish. “Wow! Not a single drop spilled!”

His phone emitted a symphony of sounds — drum beats, lasers, chimes — representing different people trying to reach him. Villaraigosa ignored them all as he explained what motivated him to run again for governor after finishing third in 2018: the people he met traveling the state in 2022 as Gov. Gavin Newsom’s infrastructure czar.

What exactly did they tell him? I asked as our main course came — three tacos for him, a taco de queso panela for me.

“Can we eat this a little bit first, and then I’ll start talking?”

Guess so!

For the next 10 minutes, we caught up on each other’s lives. He stopped eating to banter with more La Parrilla staff, eventually posing for a photo with Gabriel.

So, what exactly did the people say, who were asking him to run?

“You know, I never asked.”

Villaraigosa figured it was his record in Sacramento and Los Angeles, working across the proverbial political aisle to get things done.

Do you think Californians want that, though?

“Well, they obviously didn’t want it last time!” Villaraigosa chortled. “But I think people are ready for it.”

Then-mayoral candidate Antonio Villaraigosa, center, and then-Assemblywoman and now-Mayor Karen Bass, left, during an endorsement celebration at his South Los Angeles headquarters in 2005.

(Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

The main campaign planks swung left and right — strengthening Medi-Cal (“Health care is a right”) while also making California friendlier for small businesses (“You could be pro-worker and pro-business. I was. I don’t think these are contradictions”). Building more housing by “streamlining permitting,” while doubling down on public transit.

“I’m from Boyle Heights, so I know a little Yiddish, OK?” Villaraigosa said at one point. “I’m a schlepper.”

He recounted getting a phone call from his deputy mayor for economic development about a guy who wanted to open an operations center in the San Fernando Valley.

“He’s really pissed off because it’s taken so long,” Villaraigosa recalled the deputy mayor telling him. “Said, ‘You want to call him?’ I didn’t know who he was.”

It was Elon Musk.

“And so I called him up, and he’s very upset. Said too much bureaucracy and red tape in the city. I told him to slow down — ‘Tell me what the problem is.’ He told me. We got it done in three months.

“That’s your job when you’re mayor,” Villaraigosa continued. “And that’s your job when you’re governor. I think you’re going to see a guy who’s going to run … .”

He pointed to the photo of him on the wall.

“You know, you said, ‘What’s the same?’ I’m still that guy that rolls up my sleeves. I wanted to get to a goal last night. I worked all the way into the evening to do it. That’s the way I am.”

A server brought over a cup of hot water with honey on the side for Villaraigosa, as I posed my final question. He will be 73 in 2026, making him the oldest first-term governor in California history if elected. Did that concern him?

His million-dollar smile flashed.

“Honestly, the only people who have asked that question are reporters. It’s funny, one of them compared me to Joe Biden. And I started laughing.”

Yet another ringtone buzzed from Villaraigosa’s phone.

“This campaign is going to be about the future. It’s going to be about the high cost of an education for young people. It’s going to be about the high cost of housing for young people.”

He leaned directly into my phone, which had been lying on the table between us while recording our conversation.

“I was in the gym this morning at 4:50 in the morning. I’m in the gym six days a week. I hike, I work out, I eat well, I’m ready for this campaign.”

He soon got up and offered a fist bump.

“You’re the best, bro. I got to go.”

Villaraigosa threw down cash to cover his share of our lunch and headed out the door. “Hi, how are you?” I heard as he walked out.

A minute later, my phone rang. He had gotten a parking ticket.

“I was going back to my car, and the parking guy was printing it out,” he said with a laugh. “He realized who I was and began to apologize — ‘I’m so sorry, I’m a big fan. I wish I didn’t have to do this, but I have to.’”

Villaraigosa laughed again. “I told him, ‘You’re doing your job, don’t worry about it. Gimme the ticket, it’s on me.’”

He let a beat pass, then laughed one more time. “Sixty-three bucks! Sixty. Three. Bucks. We’ll talk later, bro.”