Caracas, Venezuela – As dark clouds hung above an unusually empty street in the neighbourhood of Petare, Eglle Camacho started to hear a dull, rhythmic clanging.

The noise soon crescendoed. From their windows and doorways, people stood armed with kitchen utensils, banging spoons against pans. They started to spill onto the street. Camacho decided to join them.

Their impromptu march cascaded towards the centre of Venezuela’s capital of Caracas on Monday, scooping up thousands of people on foot and motorbikes.

What brought them all together was outrage over what they saw as fraudulent election results announced in favour of President Nicolas Maduro.

Camacho took lots of photos that day – the smiles, the flags and even the violence – but she told Al Jazeera she has since deleted all of them. She fears what Maduro’s government may do to the protesters who support the opposition’s claims to victory.

“There is so much persecution,” Camacho said from her home in Petare. “They’re coming into neighbourhoods to look for people.”

That fear has been widespread in the days following July 28’s presidential election.

For weeks, opinion polls ahead of the vote had suggested Maduro would lose to retired diplomat Edmundo Gonzalez, provided that elections were free and fair. Maduro’s rival had a sizeable lead – about 30 points. Exit polls reflected a similar trend.

But when Venezuela’s National Electoral Council (CNE) announced the outcome of the vote early on Monday morning, it told a different story. The government agency claimed Maduro had won with more than 51 percent of the vote, a comfortable seven points ahead of Gonzalez.

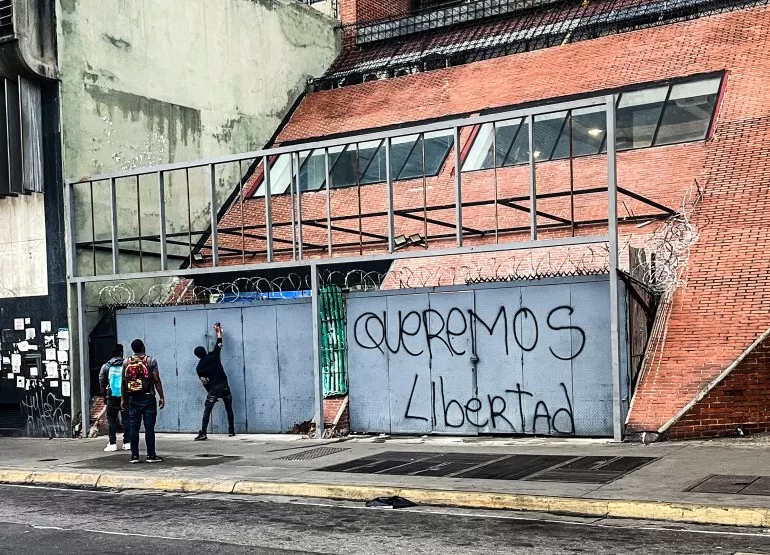

Demonstrations began, and clashes between opposition supporters and security forces ensued. Some have led to detentions, injuries and even death.

After days of turbulence, many opposition supporters are in no man’s land, navigating a narrow path between hope and fear over what comes next.

Jorge Fermin, 86, has been protesting for years against the socialist regime in Venezuela, first under the late Hugo Chavez and then under his hand-picked successor, Maduro.

At a gathering in central Caracas, the former Ministry of Education worker waves a homemade poster in the air.

The poster offers an optical illusion: Seen from one side, it shows Gonzalez’s face. Look at it from another angle, though, and it shows Maria Corina Machado, the candidate who was meant to run against Maduro, only to be banned from public office.

“This is the biggest lie in the world,” Fermin said of the CNE’s results. “The government knows the true result but they don’t want to show it.”

Maduro’s government has so far failed to publish the voting tallies from individual polling stations, as has been the tradition in the past. All the CNE has offered is the overall percentage.

However, tallies collected by poll monitors – and handed to the opposition – appear to show Gonzalez won with a landslide, securing 67 percent of the vote.

Despite calls from the opposition, as well as the international community, the government has not yet shown any proof that Maduro officially won. Maduro has pledged to reveal the voting tallies, but a timeline has not yet been set.

“This government has caused so much pain, misery, and now they have tried to rob us of our last remaining hope,” Fermin told Al Jazeera.

As a retiree in Venezuela, his pension is equivalent to just $3.50 a month. “It doesn’t even allow me to top up my phone,” he explained.

The pro-Maduro posters that once decorated almost every lamp post in Caracas have now vanished, torn down and thrown onto rubbish heaps or fires. A number of statues representing the late Chavez, seen as the father of Venezuela’s socialist project, have also been toppled.

Margarita Lopez, a Venezuelan historian who has studied the country’s protest movement and Chavez’s socialist government, told Al Jazeera that today’s demonstrations share the hallmarks of past mobilisations: the ripping down of statues, the banging of pots and pans in a style of protest called “cacerolazo”.

But this time, she said, there is one key difference. “The polarisation has gone,” she explained.

Previous protests, Lopez pointed out, were largely made up of middle- and upper-class voters. But with Venezuela’s economy in continued decline, a more diverse cross-section of society has poured out on the streets to demonstrate.

“Everyone is struggling with work,” Lopez said. “They’ve gotten poorer. They don’t have full access to public services. The political discourse of polarisation isn’t valid any more for Venezuelans.”

Traditionally, many residents in working-class areas of Venezuela were followers of Chavismo – the ideology named after Chavez, which promotes income redistribution and resistance against “imperial” forces, represented by countries like the United States.

But for many, Chavismo has not lived up to its expectations. After Chavez’s death in 2013, Maduro took over the government, and the country tumbled into an economic abyss.

Part of the problem was the global fall in oil prices in 2014, but the crisis was also due to poor economic mismanagement, embezzlement of state funds and international sanctions.

“I’ve come from Petare. I’m here for the freedom of my county, for the future of my daughter, for my sister, for my niece,” a shirtless man cried at one recent protest, as he raised one hand in the air.

He used the other to point towards the tattoo on his chest: a colourful map of Venezuela.

According to Lopez, low-income areas like Petare were once bastions of Chavismo. But for residents there today, the socialist rhetoric feels no longer relevant.

“Maduro can say imperialism and the ‘fascist’ right-wing opposition haven’t yet been stopped, but in reality, people aren’t interested any more,” Lopez explained.

The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) has contracted by 80 percent over the last few years, according to the International Monetary Fund. Salaries and pensions have dwindled due to hyperinflation, currency devaluation and informal dollarisation, a process that arises when people turn to the US dollar as an alternative currency.

An estimated 7.7 million people – a quarter of the population – have left the country due to low salaries, a lack of opportunity, poor healthcare and, in some cases, persecution.

Human rights groups like Amnesty International have long criticised the Maduro government for using arbitrary arrests, forced disappearances and even extrajudicial killings to squash perceived dissent.

“I can’t support seeing blood in my country – a country that has so much to offer,” Camacho said, days after first hearing the banging of pots on Monday in Petare.

The mother of two emigrated once before, and she is now concerned she might have to leave again. “If this government doesn’t fall, I’m going. I’ll have to. I can’t continue here – they’ll put me in prison.”

At least 19 people have been killed so far in clashes between security forces and opposition supporters, according to the nongovernmental organisation Victim Monitor. At least six were assassinated by colectivos, groups of armed men linked to the government, mounted on motorbikes and carrying weapons.

Victim Monitor reports that more than 1,000 people have also been detained, refused access to legal assistance and unable to see their families.

Student Marta Diaz, who used a pseudonym for security reasons, had already been to a couple of demonstrations in the mountain city of Merida when she joined a protest to demand the release of 17 young people detained after the election. One of them was her cousin.

“I felt really bad. I even had a kind of panic attack,” Diaz said. “I feel hopeless. It’s difficult to keep hope in such a dark situation.”

But despite her fears of repression, she does not want to give up the fight to secure her cousin’s release – and push for a transparent election result. “I’ll go to more protests. I’m scared, of course, but I’ll go to as many as necessary.”

In a television address on state TV on Thursday, Maduro announced the construction of two high-security prisons for detainees related to the protests. He said these would be “reeducation camps”, where prisoners would be required to participate in forced labour.

Nevertheless, Fermin, proudly donning his Venezuela flag cap, told Al Jazeera he refuses to lose his optimism that the opposition can prevail.

“The day I stop fighting, I will fall,” he said, cautiously hopeful that soon Venezuela will see a new government and a brighter future.